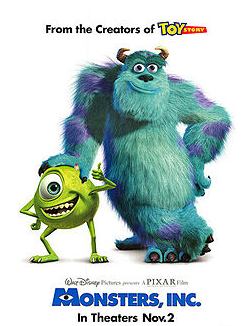

Monsters, Inc. is a 2001 American computer-animated comedy film directed by Pete Docter, released by Walt Disney Pictures, and the fourth film produced by Pixar Animation Studios. Co-directed by Lee Unkrich and David Silverman, the film stars two monsters who work for a company named Monsters, Inc.: top scarer James P. Sullivan (voiced by John Goodman)—known as "Sulley"—and his one-eyed assistant and best friend, Mike Wazowski (voiced by Billy Crystal). Monsters generate their city's power by scaring children, but they are terribly afraid themselves of being contaminated by children, so when one enters Monstropolis, Sulley finds his world disrupted.

Docter began developing the film in 1996 and wrote the story with Jill Culton, Jeff Pidgeon, and Ralph Eggleston. Fellow Pixar director Andrew Stanton wrote the screenplay with screenwriter Daniel Gerson. The characters went through many incarnations over the film's five-year production process. The technical team and animators found new ways to render fur and cloth realistically for the film. Randy Newman, who composed Pixar's three prior films, returned to compose their fourth.

Although the film suffered negative publicity in the form of two lawsuits against the filmmakers, filed by Lori Madrid and Stanley Mouse respectively, that were ultimately dismissed, Monsters, Inc. proved to be a major box office success from its release on November 2, 2001, generating over $562 million worldwide. In addition, Monsters, Inc. received highly positive reviews from critics and audiences, who praised both the humor and heart of the film.

Monsters, Inc. saw a 3D re-release in theaters on December 19, 2012. Its prequel, Monsters University, directed by Dan Scanlon and written by Docter and Stanton, is scheduled to be released on June 21, 2013.

Plot

The parallel city of Monstropolis is inhabited by monsters and powered by the screams of children in the human world. At the Monsters, Inc. factory, employees called "Scarers" venture into children's bedrooms to scare them and collect their screams, using closet doors as portals. This is considered a dangerous task since the monsters believe children to be toxic and that touching them would be fatal. However, production is falling as children are becoming harder to scare and the company chairman Henry J. Waternoose III is determined to find a solution. The top Scarer is James P. "Sulley" Sullivan, who lives with his assistant and best friend Mike Wazowski and has a rivalry with the ever-determined chameleon-like monster Randall Boggs. During an ordinary day's work on the "Scarefloor", fellow Scarer George Sanderson accidentally brings a child's sock into the factory, causing the Child Detection Agency (CDA) to arrive and cleanse him. Mike is harassed by Roz the clerk for never completing his paperwork on time.

While going to file Mike's paperwork, Sulley discovers that Randall left an activated door on the Scarefloor in an attempt of cheating and a young girl has entered the factory, much to Sulley's horror. After a few failed attempts to put her back, he places her in his bag and hides when Randall arrives and returns the door to storage. Mike and his girlfriend Celia are on a date at Harryhausen's when Sulley comes to him for help, but chaos erupts when the girl is discovered in the restaurant, and the CDA is called. Sulley and Mike escape the CDA and take the girl home, discovering that she is not toxic after all. Sulley quickly grows attached to the girl and names her "Boo". The next day, they smuggle her into the factory and Mike attempts to return her through her door. Randall tries to kidnap Boo, but kidnaps Mike by mistake.

In the basement, Randall reveals to Mike he has built a torture machine ("Scream Extractor") to extract children's screams, which would make the company's current tactics redundant. Randall straps Mike to the chair for experimentation but Sulley stops Randall from using the machine on Mike (replacing him with Fungus, Randall's assistant) and reports him to Waternoose, accidentally scaring Boo in the process. However, Waternoose is revealed to be in allegiance with Randall and he exiles Mike and Sulley to the Himalayas. The two are taken in by the Abominable Snowman, who tells them they can return to the factory through the nearby village. Sulley heads out, but Mike refuses to follow him out of frustration, believing their current situation to be Sulley's fault. Sulley returns to the factory and rescues Boo from the Scream Extractor. Mike returns to apologise to Sulley and inadvertently helps Sulley defeat Randall in a fight.

Randall pursues Mike and Sulley as they race to the factory and ride on the doors heading into storage, taking them into a giant vault where millions of closet doors are stored. Boo's laughter activates the doors and allows the chase to pass in and out of the human world. After Boo stops Randall from pushing Sulley out of an open door, Sulley and Mike trap him in the human world using a door to a Southern trailer park, where he is mistaken for an alligator and beaten up by a pair of hillbillies.

They are finally able to access Boo's door, but Waternoose and the CDA send it back to the Scarefloor. Mike distracts the CDA, while Sulley escapes with Boo and her door while Waternoose follows. Waternoose is tricked into confessing his plan to kidnap children in the simulation bedroom and is arrested by the CDA, although Waternoose blames Sulley for destroying the company. The CDA's leader, #001, is revealed to be Roz, who has been undercover for 2 1/2 years trying to prove there was a scandal at Monsters Inc. Sulley and Mike say goodbye to Boo and return her home; on Roz’s orders Boo’s door is then destroyed. Sulley becomes the new chairman of Monsters Inc., and thanks to his experience with Boo, he comes up with a plan to end the company's energy crisis.

Months later, Sulley's leadership has changed the company's workload. The monsters now enter children's bedrooms to entertain them, since laughter is ten times more powerful than screams. Mike takes Sulley aside, revealing he has almost rebuilt Boo's door, requiring only one more piece which Sulley took as a memento. Sulley enters and is able to reunite with Boo.

Animation

In November 2000, early in the production of Monsters, Inc., Pixar packed up and moved for the second time since its Lucasfilm years. The company's approximately 500 employees had become spread among three buildings, separated by a busy highway. The company moved from Point Richmond to a much bigger campus, co-designed by Lasseter and Steve Jobs, in Emeryville.

In production, Monsters Inc. differed from earlier Pixar features in that each main character had its own lead animator: John Kahrs on Sulley, Andrew Gordon on Mike, and Dave DeVan on Boo. Kahrs found that the "bearlike quality" of Goodman's voice provided an exceptionally good fit with the character. He faced a difficult challenge, however, in dealing with Sulley's sheer mass; traditionally, animators conveyed a figure's heaviness by giving it a slower, more belabored movement, but Kahrs was concerned that such an approach to a central character would give the film a sluggish feel. Like Goodman, Kahrs came to think of Sulley as a football player, one whose athleticism enabled him to move quickly in spite of his size. To help the animators with Sulley and other large monsters, Pixar arranged for Rodger Kram, a University of California, Berkeley expert on the locomotion of heavy mammals, to lecture on the subject.

Adding to Sulley's lifelike appearance was an intense effort by the technical team to refine the rendering of fur. Other production houses had tackled realistic fur, most notably Rhythm & Hues in its 1993 polar bear commercials for Coca-Cola and in its talking animals' faces in Babe (1995). Monsters, Inc., however, required fur on a far larger scale. From the standpoint of Pixar's engineers, the quest for fur posed several significant challenges. One was figuring out how to animate the huge numbers of hairs—2,320,413 on Sulley—in a reasonably efficient way. Another was making sure the hairs cast shadows on other hairs. Without self-shadowing, fur or hair takes on an unrealistic flat-colored look (The hair on Andy's toddler sister, as seen in the opening sequence of Toy Story, is an example of hair without self-shadowing.)

The first fur test was with Sullivan running an obstacle course. Results were not satisfactory, as fur would get caught by objects and stretch the fur out because of the extreme amount of motion. Another similar test was also unsuccessful with the fur going through the objects.

Eventually Pixar set-up the Simulation department and created a new fur simulation program called Fizt (for "physics tool"). After a shot with Sulley had been animated, the Simulation department took the data for the shot and added his fur. Fizt allowed the fur to react in a natural way. When Sully moved the fur would automatically react to his movements, taking into account the effects of wind and gravity as well. The Fizt program also controlled movement on Boo's clothing, which provided another breakthrough. The deceptively simple-sounding task of animating cloth was also a challenge to animate because of the hundreds of creases and wrinkles that automatically occurred in the clothing when the wearer moved. It also meant solving the complex problem of how to keep cloth untangled—that is, how to keep it from passing through itself when parts of it intersect. With the Fizt program, it applied the same system as Sulley's fur. Boo would first be animated shirtless and the Simulation department would use the Fizt program to apply the shirt over Boo's body and when she moved her clothes would react to her movements in a natural manner.

To solve the problem of cloth-to-cloth collisions, Michael Kass, Pixar's senior scientist, was joined on Monsters, Inc. by David Baraff and Andrew Witkin and developed an algorithm they called "global intersection analysis" to handle the problem. The complexity of the shots in Monsters, Inc. — including elaborate sets such as the door vault — required more computing power to render than any of Pixar's earlier efforts combined. The render farm in place for Monsters, Inc. was made up of 3500 Sun Microsystems processors, compared with 1400 for Toy Story 2 and only 200 for Toy Story.

Reception

Box office

Monsters, Inc. ranked No. 1 at the box office its opening weekend, grossing $62,577,067 in North America alone. The film had a small drop-off of 27.2% over its second weekend, earning another $45,551,028. In its third weekend, the film experienced a larger decline of 50.1%, placing itself in the second position just after Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. In its fourth weekend, however, there was an increase of 5.9%. Making $24,055,001 that weekend for a combined total of over $525 million. It is the seventh biggest (in US$) fourth weekend ever for a film.

As of 2013, the film has made $289,482,725 in North America, and $272,900,000 in other territories, for a worldwide total of $562,382,725. The film is Pixar's sixth highest-grossing film worldwide and fourth in North America. For a time, the film went on to take the place of Toy Story 2 as the second highest-grossing animated film of all time, behind only The Lion King.

In the U.K., Ireland and Malta, it earned £37,264,502 ($53,335,579) in total, marking the sixth highest-grossing animated film of all time in the country and the thirty-second highest-grossing film of all time. In Japan, although earning $4,471,902 during its opening and ranking second behind The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring for the weekend, on subsequent weekends it moved to first place due to exceptionally small decreases or even increases and dominated for six weeks at the box office. It finally reached $74,437,612, standing as 2002's third highest-grossing film and the third largest U.S. animated feature of all time in the country behind Toy Story 3 and Finding Nemo.

Critical reception

Monsters, Inc. received very positive reviews from critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 96% of critics gave the film a positive review based on 190 reviews, with an average score of 8/10. The critical consensus was: "Even though Monsters, Inc. lacks the sophistication of the Toy Story series, it is a still delight for children of all ages." Another review aggregator, Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 top reviews from mainstream critics, calculated a score of 78 based on 34 reviews. Charles Taylor from Salon.com stated: "It's agreeable and often funny, and adults who take their kids to see it might be surprised to find themselves having a pretty good time."

Elvis Mitchell from The New York Times gave a positive review, praising the film's use of "creative energy": "There hasn't been a film in years to use creative energy as efficiently as Monsters, Inc." Although Mike Clark from USA Today thought the comedy was sometimes "more frenetic than inspired and viewer emotions are rarely touched to any notable degree," he thought the film to be as "visually inventive as its Pixar predecessors."

ReelViews film critic James Berardinelli, who gave the film 3½ stars out of 4 wrote, saying that Monsters, Inc. was "one of those rare family films that parents can enjoy (rather than endure) along with their kids." Roger Ebert, film critic from Chicago Sun-Times, who gave the film 3 out of 4 stars, called the film "cheerful, high-energy fun, and like the other Pixar movies, has a running supply of gags and references aimed at grownups."

Lisa Schwarzbaum, a film critic for Entertainment Weekly, giving the film a B, praised the film's animation, stating "Everything from Pixar Animation Studios, the snazzy, cutting-edge computer animation outfit, looks really, really terrific, and unspools with a liberated, heppest-moms-and-dads-on-the-block iconoclasm."

Accolades

Monsters, Inc. won the Academy Award for Best Original Song (Randy Newman, after fifteen previous nominations, for If I Didn't Have You). It was one of the first animated films to be nominated for Best Animated Feature (lost to Shrek). It was also nominated for Best Original Score (lost to The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring) and Best Sound Editing (lost to Pearl Harbor).

At the Kid's Choice Awards in 2002, it was nominated for "Favorite Voice in an Animated Movie" for Billy Crystal (who lost to Eddie Murphy in Shrek).

American Film Institute Lists

AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

If I Didn't Have You – Nominated

AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Animated Film