Asylum Fraud in Chinatown: An Industry of Lies

NY Times | 2014-02-25 16:13

A Chinese woman walked into a law office in New York’s Chinatown and asked to see her lawyer. She had applied for asylum, claiming that she had been forced to get an abortion in China to comply with the country’s family-planning laws, and she was anxious about her coming interview with immigration officials.

She had good reason to be worried: Her claim, invented by her lawyer’s associates, was false.

But the lawyer, John Wang, told her to relax. The process, he said, was straightforward, and as long as she memorized a few details, everything would be fine. “You are making yourself nervous,” he said in Mandarin. “All you would be asked is the same few rubbish questions.”

“Just make it up,” the lawyer added.

The conversation, in December 2010, was secretly recorded by federal officials conducting a wide investigation of immigration fraud in New York’s Chinese population. The inquiry has led to the prosecution of at least 30 people — lawyers (including Mr. Wang), paralegals, interpreters and even an employee of a church, who is on trial, accused of coaching asylum applicants in basic tenets of Christianity to prop up their claims of religious persecution.

All were charged with helping hundreds of Chinese immigrants apply for asylum using false tales of persecution.

The transcript of the conversation in Mr. Wang’s office, which was disclosed in a recent court filing, offered a rare look at the hidden side of the Chinese asylum industry in New York.

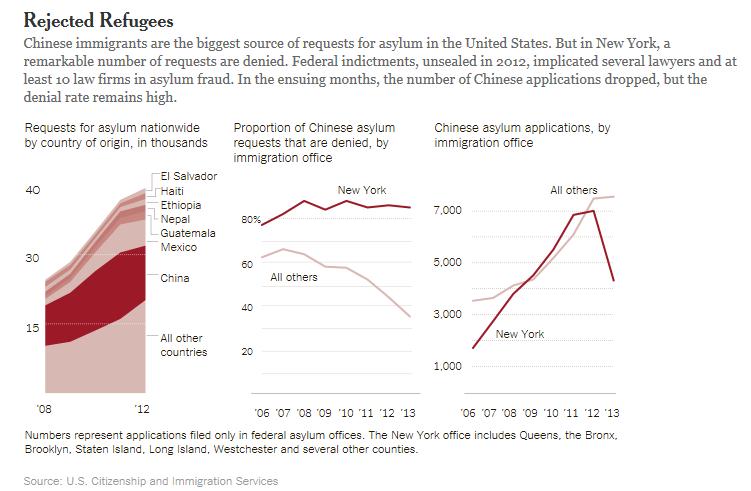

More Chinese immigrants apply for asylum than any other immigrant group in the country, with the Chinese population in New York leading the way: Over the past six years, about half of all applications filed by Chinese immigrants not facing deportation were submitted in New York City. (Comparable data for asylum applications from those in deportation proceedings was not available.)

In fiscal year 2012, Chinese immigrants filed more than 62 percent of all asylum cases received by the federal asylum office in New York, which in recent years has received more Chinese applications than the next 10 nationalities combined.

Though the prevalence of fraud is unknown, federal officials appear to regard the applicant pool in New York with considerable suspicion. In fiscal year 2013, asylum officers around the country granted 40 percent of all Chinese asylum requests, according to government data. In New York City, asylum officers approved only 15 percent.

Peter Kwong, a professor at the City University of New York and an expert on the Chinese population in New York, said it was an open secret in the Chinese community that most asylum applications were at least partly false, from fabricated narratives of persecution to counterfeit supporting documents and invented witness testimony.

To asylum-seekers, he said, “it’s not an issue of right or wrong. It’s an issue about whether they can get it and their means to get it.”

The growth in the Chinese asylum industry over the past decade has coincided with an increase in Chinese migration to the United States and in the number of Chinese arriving on temporary visas, some with the intention of staying. Many have made New York City their primary destination. Between 2000 and 2011, the foreign-born Chinese population in New York City grew by a third, to more than 350,000 from about 261,500, and is now on the verge of overtaking Dominicans as the city’s largest immigrant group, according to New York’s City Planning Department.

As an increasing number of Chinese have sought permanent immigration status here, asylum has become a popular way to achieve it: Asylum recipients are granted immediate permission to work and can apply for a green card a year later. Amid this rising demand, an ecosystem of law offices and other businesses specializing in asylum — not to mention a darker subculture of forgers and fake lawyers — has flourished in the crowded office buildings of Manhattan’s Chinatown and above storefronts along the bustling streets of Chinese enclaves in Flushing, Queens, and Sunset Park, Brooklyn.

The trade has generated healthy revenues. Some firms ask $1,000 to handle a case, then they add incremental fees that might total more than $10,000 — steep for most of the applicants, many of whom are restaurant and construction workers, nannies and manicurists.

But some involved in the business say they are motivated more by politics and moral principles than by money.

“We are doing work like the last stop on the Underground Railroad,” said David Miao, the owner of an immigration law office in Chinatown. He was among those indicted in the investigation that also implicated Mr. Wang; the case became public with the unsealing of nine indictments and a series of raids in December 2012. He has pleaded not guilty to conspiracy to commit immigration fraud.

“If we didn’t do this, they will be sent back to China,” he said in an interview. “We save lives.”

The volume of petitions has clogged the federal bureaucratic machinery, overwhelming asylum officers and judges. The deputy director of the New York asylum office blamed fraud, in part, for the deluge, and said she had tripled her team of asylum officers to dig out of a two-year backlog of cases.

The schemes “wreaked havoc on the asylum system as a whole,” the official, Ashley B. Caudill-Mirillo, wrote in a letter to a federal judge in November.

The 2012 indictments appear to have disrupted, at least temporarily, the surge of Chinese asylum applications in New York. But when asked to comment publicly about how extensive asylum fraud remains among Chinese applicants, most officials declined.

Speaking privately, however, they concurred with the prevailing opinion in the Chinese diaspora: that the problem is ubiquitous and that one high-profile case will not curb it.

The United States has a long tradition of offering refuge to foreigners fleeing persecution. Whether in the country legally or not, immigrants can petition for asylum within one year of arriving. They must show they are unable or unwilling to return to their country because they have “a well-founded fear of persecution” based on their race, religion, nationality or membership in a particular social or political group.

In fiscal year 2012, about 56,400 asylum applications were filed in asylum offices or in courts throughout the country. In the same year, about 29,500 people were granted asylum, the most since 2002, when 37,000 received it.

False asylum petitions are among the most common forms of immigration fraud, in part because they are difficult to detect, experts said. Since many claims are based on events that took place amid armed conflict or political turmoil, the narratives and supporting documents can be hard for the American authorities to verify.

And while the Chinese asylum pool has drawn increasing scrutiny in recent years, asylum fraud cuts across all immigrant groups, officials say, cropping up among populations from societies in turmoil such as Guineans seeking refuge from political upheaval, Afghans fleeing war, Russians looking for sanctuary from homophobia and Mexicans running from drug violence.

Among the Chinese, the vast majority of applicants claim they were either forced to endure abortions or sterilization under China’s family planning laws or that they fear persecution based on their adherence to Christianity or their participation in banned groups like the Chinese Democracy Party and Falun Gong, a spiritual movement that has been labeled a cult by the government.

And while many such claims are legitimate, officials and industry specialists said, an untold number are not. Mr. Kwong said the cases were easy to fake.

“The law itself provides a huge loophole, and that loophole cannot be closed because of the politics,” he said.

Sometimes the fraud consists of little more than embellishing stories to make them seem more believable. Other times, the accounts are complete fiction.

Narratives and documents are recycled from client to client, with the names and dates changed — though sometimes the lawyers forget to do even that.

David Miao, who owns a law office in Chinatown, has pleaded not guilty to immigration fraud. “We save lives,” he said.

Several immigrants said in interviews in Chinatown and Flushing that while their cases were based on true stories of persecution, some of the documents supporting their claims were false. (Many Chinese immigrants interviewed for this article agreed to talk only on the condition of anonymity.)

A well-connected member of the Taiwanese community in Queens said that while working at an immigration law office in Queens several years ago, one of his tasks was to use Photoshop to superimpose clients’ faces onto file photos of people who had been beaten by the police in China. “Everything was prefabricated,” he said.

In Flushing and other Chinese enclaves, many churches give attendance receipts to help parishioners prove their Christian faith to asylum officers. It is widely believed in the Chinese community that the pews are full of as many nonbelievers as true believers.

The dozens of people rounded up in 2012, including employees of at least 10 law firms, were accused of “weaving elaborate fictions” on behalf of hundreds of clients and coaching them on how to lie during their asylum interviews and in court. One of the lawyers would sign blank asylum petitions and let others fill them out with stories he never reviewed, prosecutors said.

Victor You, a star witness for the prosecution who worked as an assistant at several law firms and pleaded guilty to immigration fraud, said he would craft a story based on characteristics like clients’ ages and schooling. He would feed the Falun Gong narrative to uneducated immigrants because it was easiest to remember, he said in court testimony last week. Christianity claims went to young immigrants with at least a high school education.

When clients veered off-script during interviews with asylum officers, prosecutors said, some interpreters would falsely translate the client’s words.

Liying Lin, a defendant who worked at a church in Flushing, would give paid lessons in the basics of Christianity for immigrants seeking asylum for religious reasons and would coach applicants on how to lie, prosecutors said.

Ms. Lin’s trial on immigration fraud began last Tuesday. While she declined to comment for this article, her lawyer, Kenneth Paul, said in court that she was a devout Christian whose “goal was to help these individuals find God through the teachings of Christianity.”

Of the eight lawyers indicted, officials said, Mr. Wang was one of the most prolific. Between 2010 and 2012, his office filed more than 1,300 asylum petitions with the New York asylum office.

His methods were revealed in the recording of his discussion with the Chinese client, who was preparing to tell immigration officials that she had been forced to get an abortion because she had become pregnant out of wedlock.

Mr. Wang and a paralegal briefed her on the sequence of fictitious events she had to memorize: the missed period, the knock at the door, government officials hauling her to a clinic, the feeling of a medical tool inside her, the dates of her trip to the United States.

He said asylum was nearly a foregone conclusion: Cases like hers were getting approved without a problem. “It’s too easy,” he said.

More than half of the defendants have pleaded guilty, including. Mr. Wang, who was sentenced in December to two years of probation.

The indictments in 2012 cast blanket suspicion over the entire business, including applicants with legitimate claims and upstanding law practices with large Chinese clienteles. In the years before the raid, the flow of applications to the New York asylum office had risen sharply, peaking at about 7,000 in fiscal year 2012, up from about 1,700 in 2006. But after the raid, the volume plummeted, to about 4,300 in 2013, according to federal data. Immigration officials refused to speculate on the cause of the drop.

In the days after the raids, law offices and immigration agencies in Chinatown and Flushing were swarmed by clients worried about their asylum requests.

“We were looking for an expert in the law to do things a legal way,” said Zeng Hang, a cook who took a day off from his job at a Chinese restaurant in Connecticut to check on the status of his case. He was among scores of clients at 2 East Broadway, an office building in Chinatown raided by the F.B.I.

Li Bo, another cook, said he and others had assumed that if they were to entrust their cases to lawyers, then they would be in good hands. “They represent the law, do they not?” he said.

No asylum applicants were prosecuted in this case; officials have generally reserved their contempt for the lawyers, paralegals and others accused of orchestrating the frauds. At his sentencing in December, Mr. Wang, who is in his early 30s, explained that he had become an immigration lawyer “because I am also an immigrant and I want to help immigrants in this country.”

Describing himself as “young and inexperienced,” he struck a tone of remorse. “I know I made the wrong decision when I got involved in this fraud,” he said.

But in interviews, others involved in the schemes were not as contrite, rationalizing their actions.

Some said they were motivated by a compulsion to help Chinese immigrants make a better life for themselves. Those who had worked so hard to flee authoritarian rule in China, they argued, should be able to stay in the United States.

“According to my system of values, what I did is correct,” said Xu Lu, a defendant who worked as an interpreter at law firms implicated in the schemes.

“What you did is against the law but it is righteous,” he said of his actions. “You helped the weak. And you will be loved and remembered by the world.”

Share this page