Immigration Act of 1924

USINFO | 2013-10-21 15:35

President Coolidge signs the immigration act on the White House South Lawn along with appropriation bills for the Veterans Bureau. John J. Pershing is on the President's right.

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the National Origins Act, and Asian Exclusion Act (Pub.L. 68–139, 43 Stat. 153, enacted May 26, 1924), was a United States federal law that limited the annual number of immigrants who could be admitted from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were already living in the United States in 1890, down from the 3% cap set by the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, according to the Census of 1890. It superseded the 1921 Emergency Quota Act. The law was aimed at further restricting the Southern and Eastern Europeans, among them Jews who had migrated in large numbers since the 1890s to escape persecution in Poland and Russia, as well as prohibiting the immigration of Middle Easterners, East Asians, and Indians. According to the U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian the purpose of the act was "to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity".[1] Congressional opposition was minimal.

Provisions

The Immigration Act made permanent the basic limitations on immigration into the United States established in 1921 and modified the National Origins Formula established then. In conjunction with the Immigration Act of 1917, it governed American immigration policy until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which revised it completely.

For the next three years, until June 30, 1927, the 1924 Act set the annual quota of any nationality at 2% of the number of foreign-born persons of such nationality resident in the United States in 1890. That revised formula reduced total immigration from 357,803 in 1923–24 to 164,667 in 1924–25. The law's impact varied widely by country. Immigration from Great Britain and Ireland fell 19%, while immigration from Italy fell more than 90%.[2]

The Act established preferences under the quota system for certain relatives of U.S. residents, including their unmarried children under 21, their parents, and spouses aged 21 and over. It also preferred immigrants aged 21 and over who were skilled in agriculture, as well as their wives and dependent children under age 16. Non-quota status was accorded to: wives and unmarried children under 18 of U.S. citizens; natives of Western Hemisphere countries, with their families; non-immigrants; and certain others. Subsequent amendments eliminated certain elements of this law's inherent discrimination against women.

The 1924 Act also established the "consular control system" of immigration, which divided responsibility for immigration between the State Department and the Immigration and Naturalization Service. It mandated that no alien should be allowed to enter the United States without a valid immigration visa issued by an American consular officer abroad.

It provided that no alien ineligible to become a citizen could be admitted to the United States as an immigrant. This was aimed primarily at Japanese and Chinese aliens. It imposed fines on transportation companies who landed aliens in violation of U.S.immigration laws. It defined the term "immigrant" and designated all other alien entries into the United States as "non-immigrant", that is, temporary visitors. It established classes of admission for such non-immigrants.

Results

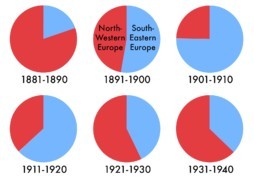

Relative proportions of immigrants from Northwestern Europe (red) and Southern and Eastern Europe (blue) in the decades before and after the immigration restriction legislation.

In the 10 years following 1900, about 200,000 Italians immigrated annually. With the imposition of the 1924 quota, 4,000 per year were allowed. By contrast, the annual quota for Germany after the passage of the Act was over 57,000. Some 86% of the 155,000 permitted to enter under the Act were from Northern European countries, with Germany, Britain, and Ireland having the highest quotas. The new quotas for immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe were so restrictive that in 1924 there were more Italians, Czechs, Yugoslavs, Greeks, Lithuanians, Hungarians, Poles, Portuguese, Romanians, Spaniards, Chinese, and Japanese that left the United States than those who arrived as immigrants.[17]

Share this page