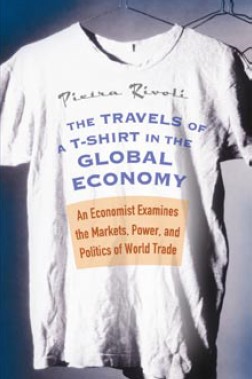

It all started at a1999 World TradeOrganization meeting.An activist protesterasked Pietra Rivoli,associate professor offinance at GeorgetownUniversity’s McDonoughSchool of Business,“Who made your Tshirt?”In her quest tofind the answer, Rivolitraveled to China,Texas, and Tanzaniaexperiencing firsthandthe complexities of the global economy. She tells the storyin her book The Travels of a T-Shirt in the GlobalEconomy: An Economist Examines the Markets,Power, and Politics of World Trade. In the followingarticle, she reflects on her experiences and marvels at howtrade has the power to pull diverse peoples together.

When I decided to follow my T-shirt aroundthe world, what I wanted most of all was totell a great story. I didn’t start out trying toprove a point or convey a lesson, though lessons surelyemerged from my travels. I just had a sense that thisvery simple thing had a complicated, fascinating storyto tell, a story that could resonate with anyone whogets dressed each morning, and I wanted to tell thatstory.I found that all over the world people like to beable to explain things to professors.

It must be somekind of perverse thrill. Whether I was at a Texascotton farm or an African T-shirt stall, people wantedme to understand their place in the global economy,wanted to explain to me how their small microcosm ofglobalization worked; they wanted me to understandhow complicated, how hard, but also how interesting itwas to face their challenges each day.

As I traveled around the world doing interviewsfor the book, I heard a lot of contrary views, opinionsabout cotton subsidies and trade policy, about Chinaand about job losses. But I didn’t meet any villains.There are no bad guys in my T-shirt’s life story. Everybusiness, every entrepreneur, every politician involvedin my T-shirt’s life was just trying to make their wayin a competitive market, a market that often changesunder their feet.I wrote this book through tumultuous and oftentragic times, through 9/11 and wars in Afghanistanand Iraq, through terrorist bombs in Europe andthrough a bitterly contested election in America.

Butas I traveled from a Texas cotton farm to a Chinesefactory, from Washington bureaucrats to a thirdgenerationused-clothing dealer descended from Jewishimmigrants, to Muslim importers in East Africa, Ikept marveling at how well everyone got along. Whilebombs were dropping, these Muslims, Jews, blacks,and whites stayed friends because of my T-shirt. Theyarn and cloth and clothing bound them together;world trade bound them together. They had no choicebut to keep talking to one another. The little guysgot along just fine while the big guys were fighting.Whatever the debates about trade, it was clear to meafter my travels that trade is very clearly an instrumentof peace and understanding. I feel privileged thateveryone I wrote about is my friend now, and I hopethe readers like all of the players in my T-shirt’s lifestory as much as I do.

I have been teaching in a business school for along time, so I know how easy it is to bore peoplewith talk of trade deficits, or competition, orunemployment. But everyone loves a good story. Somebusiness professors avoid stories in their teaching andresearch, concerned that stories lack credibility orintellectual heft. But as long as we do our best to tell the whole story, not simply anecdotes selected to proveour point, stories can go a long way in helping us tounderstand the complexities of trade and internationalbusiness. I hope my T-shirt’s story has done just that.

As a first-time book author, I have had a few “pinchmyself ” exciting moments since the book was released.The first was when I learned that Time was reviewingthe book, and the second was when I picked up thephone and found National Public Radio internationalbusiness correspondent Adam Davidson on the line.He loved the book, he said, and wanted to make anNPR series out of it. And then he gave me the highestcompliment for a professor when he said the book hadchanged the way he thought about globalization, andeven how he would report on international business inthe future.The NPR series came together over a month orso, as Adam and I traveled back to many of the placesthat I had written about, back to Texas cotton farmsand Chinese factories. On the radio, we had just 24minutes to condense my work of five years and travelsover thousands of miles, just 24 minutes to tell thebiography of this most complicated simple thing.

As Ilistened to the background sounds that Adam recordedfor the radio series—tractor noises, sewing machinenoises, cotton gin noises, and the creepy silence of apadlocked T-shirt factory in Alabama—I realized that Ihad never thought about the sounds that globalizationmakes. If you close your eyes and listen, you can hear itall working.