History of education in the United States: Colonial era

WIKIPEDIA | 2014-05-22 14:06

The history of education in the United States, or foundations of education covers the trends in educational philosophy, policy, institutions, as well as formal and informal learning in America from the 17th century to today.

New England

The first American schools in the thirteen original colonies opened in the 17th century. Boston Latin School was founded in 1635 and is both the first public school and oldest existing school in the United States. The first tax-supported public school was in Dedham, Massachusetts, and was run by Rev. Ralph Wheelock. Cremin (1970) stresses that colonists tried at first to educate by the traditional English methods of family, church, community, and apprenticeship, with schools later becoming the key agent in "socialization." At first, the rudiments of literacy and arithmetic were taught inside the family, assuming the parents had those skills. Literacy rates seem to have been much higher in New England, and much lower in the South. By the mid-19th century, the role of the schools had expanded to such an extent that many of the educational tasks traditionally handled by parents became the responsibility of the schools.

First Boston Latin School House

All the New England colonies required towns to set up schools, and many did so. In 1642 the Massachusetts Bay Colony made "proper" education compulsory; other New England colonies followed. Similar statutes were adopted in other colonies in the 1640s and 1650s. The schools were all male, with few facilities for girls. In the 18th century, "common schools," appeared; students of all ages were under the control of one teacher in one room. Although they were publicly supplied at the local (town) level, they were not free, and instead were supported by tuition or "rate bills."

The larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school. The most famous was the Boston Latin School, which is still in operation as a public high school. Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 19th century New England operated a network of elite private high schools, now called "prep schools," typified by Phillips Andover Academy(1778), Phillips Exeter Academy (1781), and Deerfield Academy (1797). They became the major feeders for Ivy League colleges in the mid-19th century. They became coeducational in the 1970s, and remain highly prestigious in the 21st century.

The South

The upper south, centered on the Chesapeake, created some basic schools early in the colonial period. In late 17th century Maryland, the Jesuits operated some schools. Generally the planter class hired tutors for the education of their children or sent them to private schools. During the colonial years, some sent their sons to England for schooling. In Virginia, rudimentary schooling for the poor and paupers was provided by the local parish. Most parents either home schooled their children using peripatetic tutors or sent them to small local private schools.

In the deep south (Georgia and South Carolina) schooling was carried on by private venture teachers and a hodgepodge of publicly funded projects. In the colony of Georgia at least ten grammar schools were in operation by 1770, many taught by ministers. The Bethesda Orphan House educated children. And dozens of private tutors and teachers advertized their service in newspapers. A study of women's signatures indicates a high degree of literacy in areas with schools. In South Carolina, scores of school projects were advertised in the South Carolina Gazette beginning in 1732. Though it is difficult to know how many ads yielded successful schools, many of the ventures advertized repeatedly over years, suggesting continuity.

After the American Revolution, Georgia and South Carolina funded public universities. In Georgia public county academies became more common, and after 1811 South Carolina opened free "common schools" for reading, writing and arithmetic. Southern states established public school systems under Reconstruction biracial governments. There were public schools for blacks, but nearly all were segregated and white legislators consistently underfunded black schools. High schools became available to whites (and some blacks) in the cities after 1900, but few rural Southerners of either race went beyond the 8th grade until after 1945.

Women and girls

The colonies of New Spain and New France are known to have had facilities for the education of girls during the 1600s, and, in New Spain, possibly farther back, as is mentioned above. The Maryland mission that the Jesuits established in 1634 is known to have had facilities for educating girls as well, because the mission's annual records report that an Indian chief "brought his daughter, seven years old, whom he loves with great affection, to be educated among the English at St. Mary's." This exemplifies not only a school for Indians, but either a school for girls, or an early co-ed school. not

The earliest continually operating school for girls in the United States is Ursuline Academy in New Orleans. It was founded in 1727 by the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula. The Academy graduated the first female pharmacist, and the first woman to contribute a book of literary merit. It contained the first convent. It was the first free school and first retreat center for ladies, and first classes for female African-American slaves, free women of color, and Native Americans. In the region, Ursuline provided the first center of social welfare in the Mississippi Valley, first boarding school in Louisiana and the first school of music in New Orleans. Tax-supported schooling for girls began as early as 1767 in New England. It was optional and some towns proved reluctant. Northampton, Massachusetts, for example, was a late adopter because it had many rich families who dominated the political and social structures and they did not want to pay taxes to aid poor families. Northampton assessed taxes on all households, rather than only on those with children, and used the funds to support a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Not until after 1800 did Northampton educate girls with public money. In contrast, the town of Sutton, Massachusetts, was diverse in terms of social leadership and religion at an early point in its history. Sutton paid for its schools by means of taxes on households with children only, thereby creating an active constituency in favor of universal education for both boys and girls.

Colonial schoolhouse in Hollis, New Hampshire

Historians point out that reading and writing were different skills in the colonial era. School taught both, but in places without schools, writing was taught mainly to boys and a few privileged girls. Men handled worldly affairs and needed to both read and write. Girls only needed to read (especially religious materials). This educational disparity between reading and writing explains why the colonial women often could read, but could not write and could not sign their names—they used an "X". There is little evidence of women teaching during the Spanish rule, although women taught each other within religious convents while also receiving instruction from priests.

The education of elite women in Philadelphia after 1740 followed the British model developed by the gentry classes during the early 18th century. Rather than emphasizing ornamental aspects of women's roles, this new model encouraged women to engage in more substantive education, reaching into the arts and sciences to emphasize their reasoning skills. Education had the capacity to help colonial women secure their elite status by giving them traits that their 'inferiors' could not easily mimic. Fatherly (2004) examines British and American writings that influenced Philadelphia during the 1740s-1770s and the ways in which Philadelphia women implemented and demonstrated their education.

Republican motherhood

By the early 19th century a new mood was alive in urban areas. Especially influential were the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, and Lydia Sigourney, who developed the role of republican motherhood as a principle that united state and family by equating a successful republic with virtuous families. Women, as intimate and concerned observers of young children, were best suited to this role. By the 1840s, New England writers such as Child, Sedgwick, and Sigourney became respected models and advocates for improving and expanding education for females. Greater educational access meant formerly male-only subjects, such as mathematics and philosophy, were to be integral to curricula at public and private schools for girls. By the late 19th century, these institutions were extending and reinforcing the tradition of women as educators and supervisors of American moral and ethical values.

The ideal of Republican motherhood pervaded the entire nation, greatly enhancing the status of women and demonstrating girls' need for education. The polish and frivolity of female instruction which characterized colonial times was replaced after 1776 by the realization that women had a major role in nation building and must become good republican mothers of good republican youth. Fostered by community spirit and financial donations, private female academies emerged in towns across the South as well as the North. Rich planters were particularly insistent on their daughters' schooling, since education served as a substitute for dowry in marriage arrangements. The academies usually provided a rigorous and broad curriculum that stressed writing, penmanship, arithmetic, and languages, especially French. By 1840, the female academies succeeded in producing a cultivated, well-read female elite ready for their roles as wives and mothers in southern aristocratic society.

Non-English schools

New Netherland had already set up elementary schools in most of their towns by 1664 (when the colony was taken over by the English). The schools were closely related to the Dutch Reformed Church, and emphasized religious instruction and prayer. The coming of the English led to the closing of the Dutch language public schools, some of which were converted into private academies. The new English government showed little interest in public schools.

German settlements from New York through Pennsylvania, Maryland and down to the Carolinas sponsored elementary schools closely tied to their churches, with each denomination or sect sponsoring its own schools. By the middle of the 19th century, German Catholics and Missouri Synod Lutherans were setting up their own German-language parochial schools, especially in cities from Cincinnati to St. Louis to Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural areas heavily settled by Germans.

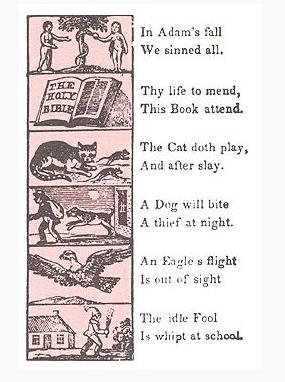

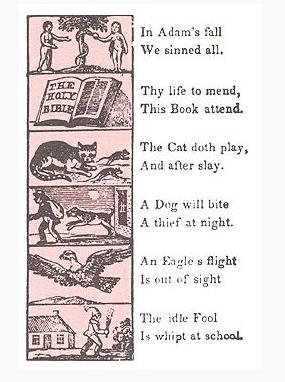

Excerpt from The New England Primer of 1690, the most popular American textbook of the 18th century

Colleges

Religious denominations established most early colleges in order to train ministers. In New England there was an emphasis on literacy so that people could read the Bible. Harvard College was founded by the colonial legislature in 1636, and named after an early benefactor. Most of the funding came from the colony, but early on the college began to build an endowment. Harvard at first focused on training young men for the ministry, but many alumni went into law, medicine, government or business. William and Mary College was founded by Virginia government in 1693, with 20,000 acres of land for an endowment, and a penny tax on every pound of tobacco, together with an annual appropriation. James Blair, the leading Anglican minister in the colony, was president for 50 years, and the college won the broad support of the Virginia gentry, most of whom were Anglicans. It trained many of the lawyers, politicians, and leading planters. Students headed for the ministry were given free tuition. Yale College was founded in 1701, and in 1716 was relocated to New Haven, Connecticut. The conservative Puritan ministers of Connecticut had grown dissatisfied with the more liberal theology of Harvard, and wanted their own school to train orthodox ministers. New Side Presbyterians in 1747 set up the College of New Jersey, in the town of Princeton; much later it was renamed Princeton University. Rhode Island College was begun by the Baptists in 1764, and in 1804 it was renamed Brown University in honor of a benefactor. Brown was especially liberal in welcoming young men from other denominations. In New York City, the Anglicans set up Kings College in 1746, with its president Samuel Johnson the only teacher. It closed during the American Revolution, and reopened in 1784 under the name of Columbia College; it is now Columbia University. The Academy of Pennsylvania was created in 1749 by Benjamin Franklin and other civic minded leaders in Philadelphia, and unlike the others was not oriented toward the training of ministers. It was renamed the University of Pennsylvania in 1791. The Dutch Reform Church in 1766 set up Queens College in New Jersey, which later became Rutgers University. Dartmouth College, chartered in 1769 relocated to its present site in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1770.

All of the schools were small, with a limited undergraduate curriculum oriented on the liberal arts. Students were drilled in Greek, Latin, geometry, ancient history, logic, ethics and rhetoric, with few discussions, little homework and no lab sessions. The college president typically tried to enforce strict discipline, and the upperclassman enjoyed hazing the freshman. Many students were younger than 17, and most of the colleges also operated a preparatory school. There were no organized sports, or Greek-letter fraternities, but the literary societies were active. Tuition was very low and scholarships were few.

There were no schools of law in the colonies. However, a few lawyers studied at the highly prestigious Inns of Court in London, while the majority served apprenticeships with established American lawyers. Law was very well established in the colonies, compared to medicine, which was in rudimentary condition. In the 18th century, 117 Americans had graduated in medicine in Edinburgh, Scotland, but most physicians learned as apprentices in the colonies. In Philadelphia, the Medical College of Philadelphia was founded in 1765, and became affiliated with the university in 1791. In New York, the medical department of King's College was established in 1767, and in 1770 awarded the first American M.D. degree.

New England

The first American schools in the thirteen original colonies opened in the 17th century. Boston Latin School was founded in 1635 and is both the first public school and oldest existing school in the United States. The first tax-supported public school was in Dedham, Massachusetts, and was run by Rev. Ralph Wheelock. Cremin (1970) stresses that colonists tried at first to educate by the traditional English methods of family, church, community, and apprenticeship, with schools later becoming the key agent in "socialization." At first, the rudiments of literacy and arithmetic were taught inside the family, assuming the parents had those skills. Literacy rates seem to have been much higher in New England, and much lower in the South. By the mid-19th century, the role of the schools had expanded to such an extent that many of the educational tasks traditionally handled by parents became the responsibility of the schools.

First Boston Latin School House

The larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school. The most famous was the Boston Latin School, which is still in operation as a public high school. Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 19th century New England operated a network of elite private high schools, now called "prep schools," typified by Phillips Andover Academy(1778), Phillips Exeter Academy (1781), and Deerfield Academy (1797). They became the major feeders for Ivy League colleges in the mid-19th century. They became coeducational in the 1970s, and remain highly prestigious in the 21st century.

The South

The upper south, centered on the Chesapeake, created some basic schools early in the colonial period. In late 17th century Maryland, the Jesuits operated some schools. Generally the planter class hired tutors for the education of their children or sent them to private schools. During the colonial years, some sent their sons to England for schooling. In Virginia, rudimentary schooling for the poor and paupers was provided by the local parish. Most parents either home schooled their children using peripatetic tutors or sent them to small local private schools.

In the deep south (Georgia and South Carolina) schooling was carried on by private venture teachers and a hodgepodge of publicly funded projects. In the colony of Georgia at least ten grammar schools were in operation by 1770, many taught by ministers. The Bethesda Orphan House educated children. And dozens of private tutors and teachers advertized their service in newspapers. A study of women's signatures indicates a high degree of literacy in areas with schools. In South Carolina, scores of school projects were advertised in the South Carolina Gazette beginning in 1732. Though it is difficult to know how many ads yielded successful schools, many of the ventures advertized repeatedly over years, suggesting continuity.

After the American Revolution, Georgia and South Carolina funded public universities. In Georgia public county academies became more common, and after 1811 South Carolina opened free "common schools" for reading, writing and arithmetic. Southern states established public school systems under Reconstruction biracial governments. There were public schools for blacks, but nearly all were segregated and white legislators consistently underfunded black schools. High schools became available to whites (and some blacks) in the cities after 1900, but few rural Southerners of either race went beyond the 8th grade until after 1945.

Women and girls

The colonies of New Spain and New France are known to have had facilities for the education of girls during the 1600s, and, in New Spain, possibly farther back, as is mentioned above. The Maryland mission that the Jesuits established in 1634 is known to have had facilities for educating girls as well, because the mission's annual records report that an Indian chief "brought his daughter, seven years old, whom he loves with great affection, to be educated among the English at St. Mary's." This exemplifies not only a school for Indians, but either a school for girls, or an early co-ed school. not

The earliest continually operating school for girls in the United States is Ursuline Academy in New Orleans. It was founded in 1727 by the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula. The Academy graduated the first female pharmacist, and the first woman to contribute a book of literary merit. It contained the first convent. It was the first free school and first retreat center for ladies, and first classes for female African-American slaves, free women of color, and Native Americans. In the region, Ursuline provided the first center of social welfare in the Mississippi Valley, first boarding school in Louisiana and the first school of music in New Orleans. Tax-supported schooling for girls began as early as 1767 in New England. It was optional and some towns proved reluctant. Northampton, Massachusetts, for example, was a late adopter because it had many rich families who dominated the political and social structures and they did not want to pay taxes to aid poor families. Northampton assessed taxes on all households, rather than only on those with children, and used the funds to support a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Not until after 1800 did Northampton educate girls with public money. In contrast, the town of Sutton, Massachusetts, was diverse in terms of social leadership and religion at an early point in its history. Sutton paid for its schools by means of taxes on households with children only, thereby creating an active constituency in favor of universal education for both boys and girls.

Colonial schoolhouse in Hollis, New Hampshire

The education of elite women in Philadelphia after 1740 followed the British model developed by the gentry classes during the early 18th century. Rather than emphasizing ornamental aspects of women's roles, this new model encouraged women to engage in more substantive education, reaching into the arts and sciences to emphasize their reasoning skills. Education had the capacity to help colonial women secure their elite status by giving them traits that their 'inferiors' could not easily mimic. Fatherly (2004) examines British and American writings that influenced Philadelphia during the 1740s-1770s and the ways in which Philadelphia women implemented and demonstrated their education.

Republican motherhood

By the early 19th century a new mood was alive in urban areas. Especially influential were the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, and Lydia Sigourney, who developed the role of republican motherhood as a principle that united state and family by equating a successful republic with virtuous families. Women, as intimate and concerned observers of young children, were best suited to this role. By the 1840s, New England writers such as Child, Sedgwick, and Sigourney became respected models and advocates for improving and expanding education for females. Greater educational access meant formerly male-only subjects, such as mathematics and philosophy, were to be integral to curricula at public and private schools for girls. By the late 19th century, these institutions were extending and reinforcing the tradition of women as educators and supervisors of American moral and ethical values.

The ideal of Republican motherhood pervaded the entire nation, greatly enhancing the status of women and demonstrating girls' need for education. The polish and frivolity of female instruction which characterized colonial times was replaced after 1776 by the realization that women had a major role in nation building and must become good republican mothers of good republican youth. Fostered by community spirit and financial donations, private female academies emerged in towns across the South as well as the North. Rich planters were particularly insistent on their daughters' schooling, since education served as a substitute for dowry in marriage arrangements. The academies usually provided a rigorous and broad curriculum that stressed writing, penmanship, arithmetic, and languages, especially French. By 1840, the female academies succeeded in producing a cultivated, well-read female elite ready for their roles as wives and mothers in southern aristocratic society.

Non-English schools

New Netherland had already set up elementary schools in most of their towns by 1664 (when the colony was taken over by the English). The schools were closely related to the Dutch Reformed Church, and emphasized religious instruction and prayer. The coming of the English led to the closing of the Dutch language public schools, some of which were converted into private academies. The new English government showed little interest in public schools.

German settlements from New York through Pennsylvania, Maryland and down to the Carolinas sponsored elementary schools closely tied to their churches, with each denomination or sect sponsoring its own schools. By the middle of the 19th century, German Catholics and Missouri Synod Lutherans were setting up their own German-language parochial schools, especially in cities from Cincinnati to St. Louis to Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural areas heavily settled by Germans.

Excerpt from The New England Primer of 1690, the most popular American textbook of the 18th century

Colleges

Religious denominations established most early colleges in order to train ministers. In New England there was an emphasis on literacy so that people could read the Bible. Harvard College was founded by the colonial legislature in 1636, and named after an early benefactor. Most of the funding came from the colony, but early on the college began to build an endowment. Harvard at first focused on training young men for the ministry, but many alumni went into law, medicine, government or business. William and Mary College was founded by Virginia government in 1693, with 20,000 acres of land for an endowment, and a penny tax on every pound of tobacco, together with an annual appropriation. James Blair, the leading Anglican minister in the colony, was president for 50 years, and the college won the broad support of the Virginia gentry, most of whom were Anglicans. It trained many of the lawyers, politicians, and leading planters. Students headed for the ministry were given free tuition. Yale College was founded in 1701, and in 1716 was relocated to New Haven, Connecticut. The conservative Puritan ministers of Connecticut had grown dissatisfied with the more liberal theology of Harvard, and wanted their own school to train orthodox ministers. New Side Presbyterians in 1747 set up the College of New Jersey, in the town of Princeton; much later it was renamed Princeton University. Rhode Island College was begun by the Baptists in 1764, and in 1804 it was renamed Brown University in honor of a benefactor. Brown was especially liberal in welcoming young men from other denominations. In New York City, the Anglicans set up Kings College in 1746, with its president Samuel Johnson the only teacher. It closed during the American Revolution, and reopened in 1784 under the name of Columbia College; it is now Columbia University. The Academy of Pennsylvania was created in 1749 by Benjamin Franklin and other civic minded leaders in Philadelphia, and unlike the others was not oriented toward the training of ministers. It was renamed the University of Pennsylvania in 1791. The Dutch Reform Church in 1766 set up Queens College in New Jersey, which later became Rutgers University. Dartmouth College, chartered in 1769 relocated to its present site in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1770.

All of the schools were small, with a limited undergraduate curriculum oriented on the liberal arts. Students were drilled in Greek, Latin, geometry, ancient history, logic, ethics and rhetoric, with few discussions, little homework and no lab sessions. The college president typically tried to enforce strict discipline, and the upperclassman enjoyed hazing the freshman. Many students were younger than 17, and most of the colleges also operated a preparatory school. There were no organized sports, or Greek-letter fraternities, but the literary societies were active. Tuition was very low and scholarships were few.

There were no schools of law in the colonies. However, a few lawyers studied at the highly prestigious Inns of Court in London, while the majority served apprenticeships with established American lawyers. Law was very well established in the colonies, compared to medicine, which was in rudimentary condition. In the 18th century, 117 Americans had graduated in medicine in Edinburgh, Scotland, but most physicians learned as apprentices in the colonies. In Philadelphia, the Medical College of Philadelphia was founded in 1765, and became affiliated with the university in 1791. In New York, the medical department of King's College was established in 1767, and in 1770 awarded the first American M.D. degree.

Share this page