Introduction: Outline of the U.S. Legal System

American Corner | 2013-02-01 16:05

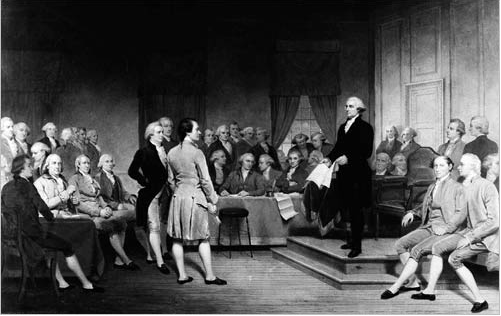

Painter Junius Brutus Searns depicted George Washington (standing, right) addressing the 1787 Constitutional Convention. (© AP Images)

(The following introduction is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, Outline of the U.S. Legal System.)

Introduction: The U.S. Legal System

By Michael Jay Friedman

Every business day, courts throughout the United States render decisions that together affect many thousands of people. Some affect only the parties to a particular legal action, but others adjudicate rights, benefits, and legal principles that have an impact on all Americans. Inevitably, many Americans may welcome a given ruling while others – sometimes many others – disapprove. All, however, accept the legitimacy of these decisions, and of the courts' role as final interpreter of the law. There can be no more potent demonstration of the trust that Americans place in the rule of law and their confidence in the U.S. legal system.

The pages that follow survey that system. Much of the discussion explains how U.S. courts are organized and how they work. Courts are central to the legal system, but they are not the entire system. Every day across America, federal, state, and local courts interpret laws, adjudicate disputes under laws, and at times even strike down laws as violating the fundamental protections that the Constitution guarantees all Americans. At the same time, millions of Americans transact their day-to-day affairs without turning to the courts. They, too, rely upon the legal system. The young couple purchasing their first home, two businessmen entering into a contract, parents drawing up a will to provide for their children – all require the predictability and enforceable common norms that the rule of law provides and the U.S. legal system guarantees.

This introduction seeks to familiarize readers with the basic structure and vocabulary of American law. Subsequent chapters add detail, and afford a sense of how the U.S. legal system has evolved to meet the needs of a growing nation and its ever more complex economic and social realities.

A FEDERAL LEGAL SYSTEM

Overview

The American legal system has several layers, more possibly than in most other nations. One reason is the division between federal and state law. To understand this, it helps to recall that the United States was founded not as one nation, but as a union of 13 colonies, each claiming independence from the British Crown. The Declaration of Independence (1776) thus spoke of "the good People of these Colonies" but also pronounced that "these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES." The tension between one people and several states is a perennial theme in American legal history. As explained below, the U.S. Constitution (adopted 1787, ratified 1788) began a gradual and at times hotly contested shift of power and legal authority away from the states and toward the federal government. Still, even today states retain substantial authority. Any student of the American legal system must understand how jurisdiction is apportioned between the federal government and the states.

The Constitution fixed many of the boundaries between federal and state law. It also divided federal power among legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government (thus creating a "separation of powers" between each branch and enshrining a system of "checks-and-balances" to prevent any one branch from overwhelming the others), each of which contributes distinctively to the legal system. Within that system, the Constitution delineated the kinds of laws that Congress might pass.

As if this were not sufficiently complex, U.S. law is more than the statutes passed by Congress. In some areas, Congress authorizes administrative agencies to adopt rules that add detail to statutory requirements. And the entire system rests upon the traditional legal principles found in English Common Law. Although both the Constitution and statutory law supersede common law, courts continue to apply unwritten common law principles to fill in the gaps where the Constitution is silent and Congress has not legislated.

SOURCES OF FEDERAL LAW: THE U.S. CONSTITUTION

Supremacy of Federal Law

During the period 1781-88, an agreement called the Articles of Confederation governed relations among the 13 states. It established a weak national Congress and left most authority with the states. The Articles made no provision for a federal judiciary, save a maritime court, although each state was enjoined to honor (afford "full faith and credit" to) the rulings of the others' courts.

The drafting and ratification of the Constitution reflected a growing consensus that the federal government needed to be strengthened. The legal system was one of the areas where this was done. Most significant was the "supremacy clause," found in Article VI:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

This paragraph established the first principle of American law: Where the federal Constitution speaks, no state may contradict it. Left unclear was how this prohibition might apply to the federal government itself, and the role of the individual state legal systems in areas not expressly addressed by the new Constitution. Amendments would supply part of the answer, history still more, but even today Americans continue to wrestle with the precise demarcations between the federal and state domains.

Each Branch Plays a Role in the Legal System

While the drafters of the Constitution sought to strengthen the federal government, they feared strengthening it too much. One means of restraining the new regime was to divide it into branches. As James Madison explained in Federalist No. 51, "usurpations are guarded against by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments." Each of Madison's "departments," legislative, executive, and judiciary, received a measure of influence over the legal system.

Legislative

The Constitution vests in Congress the power to pass legislation. A proposal considered by Congress is called a bill. If a majority of each house of Congress – two-thirds should the President veto it – votes to adopt a bill, it becomes law. Federal laws are known as statutes. The United States Code is a "codification" of federal statutory law. The Code is not itself a law, it merely presents the statutes in a logical arrangement. Title 20, for instance, contains the various statutes pertaining to Education, and Title 22 those covering Foreign Relations.

Congress' lawmaking power is limited. More precisely, it is delegated by the American people through the Constitution, which specifies areas where Congress may or may not legislate. Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution forbids Congress from passing certain types of laws. Congress may not, for instance, pass an ex post facto law (a law that applies retroactively, or "after the fact"), or levy a tax on exports. Article I, Section 8 lists areas where Congress may legislate. Some of these ("To establish Post Offices") are quite specific but others, most notably, "To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States," are less so. Obviously the power to interpret the less precise delegations is extremely important. Early in the young republic's history, the judiciary branch assumed this role and thus secured an additional and extremely vital role in the U.S. legal system.

Judicial

As with the other branches, the U.S. judiciary possesses only those powers the Constitution delegates. The Constitution extended federal jurisdiction only to certain kinds of disputes. Article III, Section 2 lists them. Two of the most significant are cases involving a question of federal law ("all Cases in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made?") and "diversity" cases, or disputes between citizens of two different states. Diversity jurisdiction allows each party to avoid litigating his case before the courts of his adversary's state.

A second judicial power emerged in the Republic's early years. As explained in Chapter 2, the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Marbury v. Madison (1803) interpreted its delegated powers to include the authority to determine whether a statute violated the Constitution and, if it did, to declare such a law invalid. A law may be unconstitutional because it violates rights guaranteed to the people by the Constitution, or because Article I did not authorize Congress to pass that kind of legislation.

The power to interpret the constitutional provisions that describe where Congress may legislate is thus very important. Traditionally, Congress has justified many statutes as necessary to regulate "commerce – among the several States," or interstate commerce. This is an elastic concept, difficult to describe with precision. Indeed, one might for nearly any statute devise a plausible tie between its objectives and the regulation of interstate commerce. At times, the judicial branch interpreted the "commerce clause" narrowly. In 1935, for instance, the Supreme Court invalidated a federal law regulating the hours and wages of workers at a New York slaughterhouse because the chickens processed there all were sold to New York butchers and retailers and hence not part of interstate commerce. Soon after this, however, the Supreme Court began to afford President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs more latitude, and today the federal courts continue to interpret broadly the commerce power, although not so broadly as to justify any legislation that Congress might pass.

Federal and state courts hear two kinds of disputes: civil and criminal. (© AP Images)

Executive

Article II entrusts to the President of the United States "the executive Power." Under President George Washington (1789-1801), the entire executive branch consisted of the President, Vice President, and the Departments of State, Treasury, War, and Justice. As the nation grew, the executive branch grew with it. Today there are 15 Cabinet-level Departments. Each houses a number of Bureaus, Agencies, and other entities. Still other parts of the executive branch lie outside these Departments. All exercise executive power delegated by the President and thus are responsible ultimately to him.

In some areas, the relationship between the executive and the other two branches is clear. Suppose one or more individuals rob a bank. Congress has passed a statute criminalizing bank robbery (United States Code, Title 18, Section 2113). (Note: Technically, the statute applies only to a bank that is federally chartered, insured, or a member of the Federal Reserve System. Possibly every bank in the United States meets these criteria, but one that did not, and could not be construed as impacting interstate commerce, would not be subject to federal legislation. Federal statutes typically recite a jurisdictional basis: in this case, the federal charter requirement.) The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a bureau within the Department of Justice, would investigate the crime. When it apprehended one or more suspects, a Federal Prosecutor (also Department of Justice) would attempt to prove the suspect's guilt in a trial conducted by a U.S. District Court.

The bank robbery case is a simple one. But as the nation modernized and grew, the relationship of the three branches within the legal system evolved to accommodate the more complex issues of industrial and post-industrial society. The role of the executive branch changed most of all. In the bank robbery example, Congress needed little or no special expertise to craft a statute that criminalized bank robbery. Suppose instead that lawmakers wished to ban "dangerous" drugs from the marketplace, or restrict the amount of "unhealthful" pollutants in the air. Congress could, if it chose, specify precise definitions of these terms. Sometimes it does so, but increasingly Congress instead delegates a portion of its authority to administrative agencies housed in the executive branch. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) thus watches over the purity of the nation's food and pharmaceuticals and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates how industries impact the earth, water, and air.

Although agencies possess only powers that Congress delegates by statute, these can be quite substantial. They can include the authority to promulgate rules that define with precision more general statutory terms. A law might proscribe "dangerous" amounts of pollutants in the atmosphere, while an EPA rule defines the substances and amounts of each that would be considered dangerous. Sometimes a statute empowers an agency to investigate violations of its rules, to adjudicate those violations, and even to assess penalties!

The courts will invalidate a statute that grants an agency too much power. An important statute called the Administrative Procedure Act (United States Code Title 5, Section 551, et. seq.) explains the procedures agencies must follow when promulgating rules, judging violations, and imposing penalties. It also lays out how a party can seek judicial review of an agency's decision.

OTHER SOURCES OF LAW

The most obvious sources of American law are the statutes passed by Congress, as supplemented by administrative regulations. Sometimes these demarcate clearly the boundaries of legal and illegal conduct – the bank robbery example again – but no government can promulgate enough law to cover every situation. Fortunately, another body of legal principles and norms helps fill in the gaps, as explained below.

Common Law

Where no statute or constitutional provision controls, both federal and state courts often look to the common law, a collection of judicial decisions, customs, and general principles that began centuries ago in England and continues to develop today. In many states, common law continues to hold an important role in contract disputes, as state legislatures have not seen fit to pass statutes covering every possible contractual contingency.

Judicial Precedent

Courts adjudicate alleged violations of and disputes arising under the law. This often requires that they interpret the law. In doing so, courts consider themselves bound by how other courts of equal or superior rank have previously interpreted a law. This is known as the principle of stare decisis, or simply precedent. It helps to ensure consistency and predictability. Litigants facing unfavorable precedent, or case law, try to distinguish the facts of their particular case from those that produced the earlier decisions.

Sometimes courts interpret the law differently. The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, for instance, contains a clause that "[n]o person? shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself." From time to time, cases arose where an individual would decline to answer a subpoena or otherwise testify on the grounds that his testimony might subject him to criminal prosecution – not in the United States but in another country. Would the self-incrimination clause apply here? The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled it did, but the Fourth and Eleventh Circuits held that it did not. (Note: The U.S. Circuit Court for the Second Circuit is an appellate court that hears appeals from the federal district courts in the states of New York, Connecticut, and Vermont. The Fourth Circuit encompasses Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, and the Eleventh Alabama, Georgia, and Florida.) This effectively meant that the law differed depending where in the country a case arose!

Higher-level courts try to resolve these inconsistencies. The Supreme Court of the United States, for instance, often chooses to hear a case when its decision can resolve a division among the Circuit courts. The Supreme Court precedent will control, or apply to all the lower federal courts. In United States v. Balsys, 524 U.S. 666 (1998), the Supreme Court ruled that fear of foreign prosecution is beyond the scope of the Self-Incrimination Clause. (Note: The numbers in this sentence comprise the citation to the Balsys decision. They indicate that the Court issued its ruling in the year 1998 and that the decision appears in volume 524 of a series called United States Reports, beginning on page 666.) This ruling became the law of the entire nation, including the Second Circuit. Any federal court subsequently facing the issue was bound by the high court ruling in Balsys. Circuit court decisions similarly bind all the District Courts within that circuit. Stare decisis also applies in the various state court systems. In this way, precedent grows both in volume and explanatory reach.

DIFFERENT LAWS, DIFFERENT REMEDIES

Given this growing body of law, it is useful to distinguish among different types of laws and of actions, or lawsuits, brought before the courts and of the remedies the law affords in each type of case.

Civil/Criminal

Courts hear two kinds of disputes: civil and criminal. A civil action involves two or more private parties, at least one of which alleges a violation of a statute or some provision of common law. The party initiating the lawsuit is the plaintiff; his opponent the defendant. A defendant can raise a counterclaim against a plaintiff or a cross-claim against a co-defendant, so long as they are related to the plaintiff's original complaint. Courts prefer to hear in a single lawsuit all the claims arising from a dispute. Business litigations, as for breach of contract, or tort cases, where a party alleges he has been injured by another's negligence or willful misconduct, are civil cases.

While most civil litigations are between private parties, the federal government or a state government is always a party to a criminal action. It prosecutes, in the name of the people, defendants charged with violating laws that prohibit certain conduct as injurious to the public welfare. Two businesses might litigate a civil action for breach of contract, but only the government can charge someone with murder.

The standards of proof and potential penalties also differ. A criminal defendant can be convicted only upon the determination of guilt "beyond a reasonable doubt." In a civil case, the plaintiff need only show a "preponderance of evidence," a weaker formulation that essentially means "more likely than not." A convicted criminal can be imprisoned, but the losing party in a civil case is liable only for legal or equitable remedies, as explained below.

Legal and Equitable Remedies

The U.S. legal system affords a wide but not unlimited range of remedies. The criminal statutes typically list for a given offense the range of fines or prison time a court may impose. Other parts of the criminal code may in some jurisdictions allow stiffer penalties for repeat offenders. Punishment for the most serious offenses, or felonies, is more severe than for misdemeanors.

In civil actions, most American courts are authorized to choose among legal and equitable remedies. The distinction means less today than in the past but is still worth understanding. In 13th century England, "courts of law" were authorized to decree monetary remedies only. If a defendant's breach of contract cost the plaintiff ?50, such a court could order the defendant to pay that sum to the plaintiff. These damages were sufficient in many instances, but not in others, such as a contract for the sale of a rare artwork or a specific parcel of land. During the 13th and 14th centuries, "courts of equity" were formed. These tribunals fashioned equitable remedies like specific performance, which compelled parties to perform their obligations, rather than merely forcing them to pay damages for the injury caused by their nonperformance. By the 19th century, most American jurisdictions had eliminated the distinction between law and equity. Today, with rare exceptions, U.S. courts can award either legal or equitable remedies as the situation requires.

One famous example illustrates the differences between civil and criminal law, and the remedies that each can offer. The state of California charged the former football star O.J. Simpson with murder. Had Simpson been convicted, he would have been imprisoned. He was not convicted, however, as the jury ruled the prosecution failed to prove Simpson's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Afterwards, Mrs. Simpson's family sued Simpson for wrongful death, a civil action. The jury in this case determined that a preponderance of the evidence demonstrated Simpson's responsibility for the death of his wife. It ordered Simpson to pay money damages – a legal remedy – to the plaintiffs.

THE ROLE OF STATE LAW IN THE FEDERAL SYSTEM

The Constitution specifically forbade the states from adopting certain kinds of laws (entering into treaties with foreign nations, coining money). Also, the Article VI Supremacy Clause barred state laws that contradicted either the Constitution or federal law. Even so, large parts of the legal system remained under state control. The Constitution had carefully specified the areas where Congress might enact legislation. The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution (1791) made explicit that state law would control elsewhere: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States, respectively, or to the people."

There nonetheless remained considerable tension between the federal government and the states – over slavery, and ultimately over the right of a state to leave the federal union. The civil conflict of 1861-65 resolved both disputes. It also produced new restrictions on the state role within the legal system: Under the Fourteenth Amendment (1868), "No State shall? deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." This amendment greatly expanded the federal courts' ability to invalidate state laws. Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which forbade racial segregation in the Arkansas state school system, relied upon this "equal protection clause."

Beginning in the mid-20th century, a number of the trends outlined above – the rise of the administrative state, a more forceful and expansive judicial interpretation of due process and equal protection, and a similar expansion of Congress' power to regulate commerce – combined to enhance the federal role within the legal system. Even so, much of that system remains within the state domain. While no state may deny a citizen any right guaranteed by the federal Constitution, many interpret their own constitutions as bestowing even more generous rights and privileges. State courts applying state law continue to decide most contractual disputes. The same is true of most criminal cases, and of civil tort actions. Family law, including such matters as marriage and divorce, is almost exclusively a state matter. For most Americans most of the time, the legal system means the police officers and courts of their own state, or of the various municipalities and other political subdivisions within that state.

This introduction offers a mere thumbnail sketch of the legal system. The remainder of the volume affords greater detail, flavor, and understanding. Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 describe respectively how the federal and state court systems have been organized, while Chapter 3 explains at length the complex question of jurisdiction. The chapter necessarily delineates the borders between the federal and state courts but it also explores the question of who may sue, and of the kinds of cases courts will hear. Chapter 4 expands the focus from the courts to the groups who appear before them. The practice of law in the United States is studied, and the typical litigants described. The chapter also explains the role played by interest groups that press particular cases to advance their social and political agendas. Chapter 5 details how the courts handle criminal cases while Chapter 6 turns the focus to civil actions. Chapter 7 describes how federal judges are selected. The final chapter explores how certain judicial decisions – those of higher courts especially – can themselves amount to a form of policy making and thus further entwine the judiciary in a complex relationship with the legislative and executive branches.

[Michael Jay Friedman is a Program Officer in the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of International Information Programs. He holds a Ph.D. in American History from the University of Pennsylvania and a J.D. degree from Georgetown University Law Center.]

Share this page