Lawyers, Litigants, and Interest Groups in the Judicial Proc

American Corner | 2013-02-01 16:52

New lawyers take their oaths as new members of the Kansas state bar. (© AP Images)

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, Outline of the U.S. Legal System.)

This chapter focuses on three crucial actors in the judicial process: lawyers, litigants, and interest groups. Judges in the United States make decisions only in the context of cases that are brought to the courts by individuals or groups who have some sort of disagreement or dispute with each other. These adversaries, commonly called litigants, sometimes argue their own cases in such minor forums as small claims courts, but they are almost always represented by lawyers in the more important judicial arenas. Following an examination of the legal profession, the chapter discusses the role of individual litigants and interest groups in the judicial process.

LAWYERS AND THE LEGAL PROFESSION

The training of attorneys and the practice of law have evolved over time in the United States. Today American lawyers practice in a variety of settings and circumstances.

Development of the Legal Profession

During the colonial period in America (1607-1776), there were no law schools to train those interested in the legal profession. Some young men went to England for their education and attended the Inns of Court. The Inns were not formal law schools, but were part of the English legal culture and allowed students to become familiar with English law. Those who aspired to the law during this period generally performed a clerkship or apprenticeship with an established lawyer.

After the American Revolution (1775-83), the number of lawyers increased rapidly, because neither legal education nor admission to the bar was very strict. The apprenticeship method continued to be the most popular way to receive legal training, but law schools began to come into existence. The first law schools grew out of law offices that specialized in training clerks or apprentices. The earliest such school was the Litchfield School in Connecticut, founded in 1784. This school, which taught by the lecture method, placed primary emphasis on commercial law. Eventually, a few colleges began to teach law as part of their general curriculum, and in 1817 an independent law school was established at Harvard University.

During the second half of the 19th century, the number of law schools increased dramatically, from 15 schools in 1850 to 102 in 1900. The law schools of that time and those of today have two major differences. First, law schools then did not usually require any previous college work. Second, in 1850 the standard law school curriculum could be completed in one year. Later in the 1800s many law schools instituted two-year programs.

In 1870 major changes began at Harvard that were to have a lasting impact on legal training. Harvard instituted stiffer entrance requirements; a student who did not have a college degree was required to pass an entrance test. The law school course was increased to two years in 1871 and to three years in 1876. Also, students were required to pass first-year final examinations before proceeding to the second-year courses.

The most lasting change, however, was the introduction of the case method of teaching. This method replaced lectures and textbooks with casebooks. The casebooks (collections of actual case reports) were designed to explain the principles of law, what they meant, and how they developed. Teachers then used the Socratic method to guide the students to a discovery of legal concepts found in the cases. Other schools eventually adopted the Harvard approach, and the case method remains the accepted method of teaching in many law schools today.

As the demand for lawyers increased during the late 1800s, there was a corresponding acceleration in the creation of new law schools. Opening a law school was not expensive, and a number of night schools, using lawyers and judges as part-time faculty members, sprang into existence. Standards were often lax and the curriculum tended to emphasize local practice. These schools' major contribution lay in making training more readily available to poor, immigrant, and working-class students.

In the 20th century, the number of people wanting to study law increased dramatically. By the 1960s the number of applicants to law schools had grown so large that nearly all schools became more selective. At the same time, in response to social pressure and litigation, many law schools began actively recruiting female and minority applicants.

Also by the 1960s, the curriculum in some law schools had been expanded to include social concerns such as civil rights law and law-and-poverty issues. International law courses also became available.

A more recent trend in law schools is an emphasis on the use of computers for everything from registration to classroom instruction to accessing court forms to student services. Also noteworthy is that more and more law schools are offering courses or special programs in intellectual property law, a field of specialization that has grown considerably in recent years. Finally, the increasing use of advertising by lawyers has had a profound impact on the legal profession. On television stations across the country one can now see lawyers making appeals to attract new clients. Furthermore, legal clinics, established to handle the business generated by the increased use of advertising, have spread rapidly.

Growth and Stratification

The number of lawyers in the United States has increased steadily over the past half century and is currently estimated at more than 950,000. Where do all the attorneys in the United States find work?

The Law School Admission Council provides some answers in The Official Guide to U.S. Law Schools, 2001 Edition. Almost three-fourths (72.9 percent) of America's lawyers are in private practice, some in small, one-person offices and some in much larger law firms. About 8.2 percent of the legal profession's members work for government agencies, roughly 9.5 percent work for private industries and associations as lawyers or managers, about 1.1 percent work for legal aid associations or as public defenders, representing those who cannot afford to pay a lawyer, and 1 percent are in legal education. Some 5 percent of the nation's lawyers are retired or inactive.

America's lawyers apply their professional training in a variety of settings. Some environments are more profitable and prestigious than others. This situation has led to what is known as professional stratification.

One of the major factors influencing the prestige level is the type of legal specialty and the type of clientele served. Lawyers with specialties who serve big business and large institutions occupy the top hemisphere; those who represent individual interests are in the bottom hemisphere.

At the top of the prestige ladder are the large national law firms. Attorneys in these firms have traditionally been known less for court appearances than for the counseling they provide their clients. The clients must be able to pay for this high-powered legal talent, and thus they tend to be major corporations rather than individuals. However, many of these large national firms often provide "pro bono" (Latin for "the public good," or free) legal services to further civil rights, civil liberties, consumer interests, and environmental causes.

The large national firms consist of partners and associates. Partners own the law firm and are paid a share of the firm's profits. The associates are paid salaries and in essence work for the partners. These large firms compete for the best graduates from the nation's law schools. The most prestigious firms have 250 or more lawyers and also employ hundreds of other people as paralegals (nonlawyers specially trained to handle many of the routine aspects of legal work), administrators, librarians, and secretaries.

A notch below those working in the large national firms are those employed as attorneys by large corporations. Many corporations use national law firms as outside counsel. Increasingly, however, corporations are hiring their own salaried attorneys as in-house counsel. The legal staff of some corporations rivals those of private firms in size. These corporations compete with the major law firms for the best law school graduates.

Instead of representing the corporation in court (a task usually handled by outside counsel when necessary), the legal division handles the multitude of legal problems faced by the modern corporation. For example, the legal division monitors the company's personnel practices to ensure compliance with federal and state regulations concerning hiring and removal procedures. The corporation's attorneys may advise the board of directors about such things as contractual agreements, mergers, stock sales, and other business practices. The company lawyers may also help educate other employees about the laws that apply to their specific jobs and make sure that they are in compliance with them. The legal division of a large company also serves as a liaison with outside counsel.

Most of the nation's lawyers work in a lower hemisphere of the legal profession in terms of prestige and do not command the high salaries associated with large national law firms and major corporations. However, they are engaged in a wider range of activities and are much more likely to be found, day in and day out, in the courtrooms of the United States. These are the attorneys who represent clients in personal injury suits, who prosecute and defend persons accused of crimes, who represent husbands and wives in divorce proceedings, who help people conduct real estate transactions, and who help people prepare wills, to name just a few activities.

Attorneys who work for the government are generally included in the lower hemisphere. Some, such as the U.S. attorney general and the solicitor general of the United States, occupy quite prestigious positions, but many toil in rather obscure and poorly paid positions. A number of attorneys opt for careers as judges at the federal or state level.

Another distinction in terms of specialization in the legal profession is that between plaintiffs and defense attorneys. The former group initiates lawsuits, whereas the latter group defends those accused of wrongdoing in civil and criminal cases.

Government Attorneys in the Judicial Process

Government attorneys work at all levels of the judicial process, from trial courts to the highest state and federal appellate courts.

Federal Prosecutors. Each federal judicial district has one U.S. attorney and one or more assistant U.S. attorneys. They are responsible for prosecuting defendants in criminal cases in the federal district courts and for defending the United States when it is sued in a federal trial court.

U.S. attorneys are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Nominees must reside in the district to which they are appointed and must be lawyers. They serve a formal term of four years but can be reappointed indefinitely or removed at the president's discretion. The assistant U.S. attorneys are formally appointed by the U.S. attorney general, although in practice they are chosen by the U.S. attorney for the district, who forwards the selection to the attorney general for ratification. Assistant U.S. attorneys may be fired by the attorney general.

In their role as prosecutors, U.S. attorneys have considerable discretion in deciding which criminal cases to prosecute. They also have the authority to determine which civil cases to try to settle out of court and which ones to take to trial. U.S. attorneys, therefore, are in a very good position to influence the federal district court's docket. Also, because they engage in more litigation in the district courts than anyone else, the U.S. attorneys and their staffs are vital participants in policy making in the federal trial courts.

Prosecutors at the State Level. Those who prosecute persons accused of violating state criminal statutes are commonly known as district attorneys. In most states they are elected county officials; however, in a few states they are appointed. The district attorney's office usually employs a number of assistants who do most of the actual trial work. Most of these assistant district attorneys are recent graduates of law school, who gain valuable trial experience in these positions. Many later enter private practice, often as criminal defense attorneys. Others will seek to become district attorneys or judges after a few years.

The district attorney's office has a great deal of discretion in the handling of cases. Given budget and personnel constraints, not all cases can be afforded the same amount of time and attention. Therefore, some cases are dismissed, others are not prosecuted, and still others are prosecuted vigorously in court. Most cases, however, are subject to plea bargaining. This means that the district attorney's office agrees to accept the defendant's plea of guilty to a reduced charge or to drop some charges against the defendant in exchange for pleas of guilty to others.

Public Defenders. Often the person charged with violating a state or federal criminal statute is unable to pay for the services of a defense attorney. In some areas a government official known as a public defender bears the responsibility for representing indigent defendants. Thus, the public defender is a counterpart of the prosecutor. Unlike the district attorney, however, the public defender is usually appointed rather than elected.

In some parts of the country there are statewide public defender systems; in other regions the public defender is a local official, usually associated with a county government. Like the district attorney, the public defender employs assistants and investigative personnel.

Other Government Lawyers. At both the state and federal levels, some government attorneys are better known for their work in appellate courts than in trial courts. For example, each state has an attorney general who supervises a staff of attorneys who are charged with the responsibility of handling the legal affairs of the state. At the federal level the Department of Justice has similar responsibilities on behalf of the United States.

The U.S. Department of Justice. Although the Justice Department is an agency of the executive branch of the government, it has a natural association with the judicial branch. Many of the cases heard in the federal courts involve the national government in one capacity or another. Sometimes the government is sued; in other instances the government initiates the lawsuit. In either case, an attorney must represent the government. Most of the litigation involving the federal government is handled by the Justice Department, although a number of other government agencies have attorneys on their payrolls.

The Justice Department's Office of the Solicitor General is extremely important in cases argued before the Supreme Court. The department also has several legal divisions, each with a staff of specialized lawyers and headed by an assistant attorney general. The legal divisions supervise the handling of litigation by the U.S. attorneys, take cases to the courts of appeals, and aid the solicitor general's office in cases argued before the Supreme Court.

U.S. Solicitor General. The solicitor general of the United States, the third-ranking official in the Justice Department, is assisted by five deputies and about 20 assistant solicitors general. The solicitor general's primary function is to decide, on behalf of the United States, which cases will and will not be presented to the Supreme Court for review. Whenever an executive branch department or agency loses a case in one of the courts of appeals and wishes a Supreme Court review, that department or agency will request that the Justice Department seek certiorari. The solicitor general will determine whether to appeal the lower court decision.

Many factors must be taken into account when making such a decision. Perhaps the most important consideration is that the Supreme Court is limited in the number of cases it can hear in a given term. Thus, the solicitor general must determine whether a particular case deserves extensive consideration by the Court. In addition to deciding whether to seek Supreme Court review, the solicitor general personally argues most of the government's cases heard by the High Court.

State Attorneys General. Each state has an attorney general who serves as its chief legal official. In most states this official is elected on a partisan statewide ballot. The attorney general oversees a staff of attorneys who primarily handle the civil cases involving the state. Although the prosecution of criminal defendants is generally handled by the local district attorneys, the attorney general's office often plays an important role in investigating statewide criminal activities. Thus, the attorney general and his or her staff may work closely with the local district attorney in preparing a case against a particular defendant.

The state attorneys general also issue advisory opinions to state and local agencies. Often, these opinions interpret an aspect of state law not yet ruled on by the courts. Although an advisory opinion might eventually be overruled in a case brought before the courts, the attorney general's opinion is important in determining the behavior of state and local agencies.

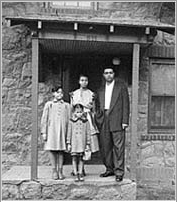

Linda Brown, left, prevailed in the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case. (© Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Private Lawyers in the Judicial Process

In criminal cases in the United States the defendant has a constitutional right to be represented by an attorney. Some jurisdictions have established public defender's offices to represent indigent defendants. In other areas, some method exists of assigning a private attorney to represent a defendant who cannot afford to hire one. Those defendants who can afford to hire their own lawyers will do so.

In civil cases neither the plaintiff nor the defendant is constitutionally entitled to the services of an attorney. However, in the civil arena the legal issues are often so complex as to demand the services of an attorney. Various forms of legal assistance are usually available to those who need help.

Assigned Defense Counsel. When a private lawyer must be appointed to represent an indigent defendant, the assignment usually is made by an individual judge on an ad hoc basis. Local bar associations or lawyers themselves often provide the courts with a list of attorneys who are willing to provide such services.

Private Defense Counsel. Some attorneys in private practice specialize in criminal defense work. Although the lives of criminal defense attorneys may be depicted as glamorous on television and in movies, the average real-life criminal defense lawyer works long hours for low pay and low prestige.

The Courtroom Workgroup

Rather than functioning as an occasional gathering of strangers who resolve a particular conflict and then go their separate ways, lawyers and judges who work in a criminal court room become part of a workgroup.

The most visible members of the courtroom workgroup – judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys – are associated with specific functions: Prosecutors push for convictions of those accused of criminal offenses against the government, defense attorneys seek acquittals for their clients, and judges serve as neutral arbiters to guarantee a fair trial. Despite their different roles, members of the courtroom workgroup share certain values and goals and are not the fierce adversaries that many people imagine. Cooperation among judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys is the norm.

The most important goal of the courtroom workgroup is to handle cases expeditiously. Judges and prosecutors are interested in disposing of cases quickly to present a picture of accomplishment and efficiency. Because private defense attorneys need to handle a large volume of cases to survive financially, resolving cases quickly works to their advantage. And public defenders seek quick dispositions simply because they lack adequate resources to handle their caseloads.

A second important goal of the courtroom workgroup is to maintain group cohesion. Conflict among the members makes work more difficult and interferes with the expeditious handling of cases.

Finally, the courtroom workgroup is interested in reducing or controlling uncertainty. In practice this means that all members of the workgroup strive to avoid trials. Trials, especially jury trials, produce a great deal of uncertainty given that they require substantial investments of time and effort without any reasonable guarantee of a desirable outcome.

To attain these goals, workgroup members employ several techniques. Although unilateral decisions and adversarial proceedings occur, negotiation is the most commonly used technique in criminal courtrooms. The members negotiate over a variety of issues – continuances (delays in the court proceedings), hearing dates, and exchange of information, for example. Plea bargaining, however, is the most critical tool of negotiation.

Legal Services for the Poor

Although criminal defendants are constitutionally entitled to be represented by a lawyer, those who are defendants in a civil case or who wish to initiate a civil case do not have the right to representation. Therefore, those who do not have the funds to hire a lawyer may find it difficult to obtain justice.

To deal with this problem, legal aid services are now found in many areas. Legal aid societies were established in New York and Chicago as early as the late 1880s, and many other major cities followed suit in the 20th century. Although some legal aid societies are sponsored by bar associations, most are supported by private contributions. Legal aid bureaus also are associated with charitable organizations in some areas, and many law schools operate legal aid clinics to provide both legal assistance for the poor and valuable training for law students. In addition, many lawyers provide legal services "pro bono publico" (Latin for "for the public good") because they see it as a professional obligation.

LITIGANTS

In some cases taken before the courts, the litigants are individuals, whereas in other cases one or more of the litigants may be a government agency, a corporation, a union, an interest group, or a university.

What motivates a person or group to take a grievance to court? In criminal cases the answer to this question is relatively simple. A state or federal criminal statute has allegedly been violated, and the government prosecutes the party charged with violating the statute. In civil cases the answer is not quite so easy. Although some persons readily take their grievances to court, many others avoid this route because of the time and expense involved.

Political scientist Phillip Cooper points out that judges are called upon to resolve two kinds of disputes: private law cases and public law controversies. Private law disputes are those in which one private citizen or organization sues another. In public law controversies, a citizen or organization contends that a government agency or official has violated a right established by a constitution or statute. In Hard Judicial Choices, Cooper writes that "legal actions, whether public law or private law contests, may either be policy oriented or compensatory."

A classic example of private, or ordinary, compensation-oriented litigation is when a person injured in an automobile accident sues the driver of the other car in an effort to win monetary damages as compensation for medical expenses incurred. This type of litigation is personal and is not aimed at changing governmental or business policies.

Some private law cases, however, are policy oriented or political in nature. Personal injury suits and product liability suits may appear on the surface to be simply compensatory in nature but may also be used to change the manufacturing or business practices of the private firms being sued.

A case litigated in North Carolina provides a good example. The case began in 1993 after a five-year-old girl got stuck on the drain of a wading pool after another child had removed the drain cover. Such a powerful suction was created that, before she could be rescued, the drain had sucked out most of her large and small intestines. As a result, the girl will have to spend about 11 hours per day attached to intravenous feeding tubes for the rest of her life. In 1997 a jury awarded the girl's family $25 million in compensatory damages and, before the jury was to have considered punitive damages, the drain manufacturer and two other defendants settled the case for $30.9 million. The plaintiff's attorney said that the lawsuit revealed similar incidents in other areas of the country and presented a stark example of something industry insiders knew but others did not. Not only did the family win its lawsuit, but the North Carolina legislature also passed a law requiring multiple drains to prevent such injuries in the future.

Most political or policy-oriented lawsuits, however, are public law controversies. That is, they are suits brought against the government primarily to stop allegedly illegal policies or practices. They may also seek damages or some other specific form of relief. A case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, provides a good example. South Carolina's Beachfront Management Act forbade David H. Lucas from building single-family houses on two beachfront lots he owned. A South Carolina trial court ruled that Lucas was entitled to be compensated for his loss. The South Carolina Supreme Court reversed the trial court decision, however, and Lucas appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The High Court ruled in Lucas's favor, saying that if a property owner is denied all economically viable use of his or her property, a taking has occurred and the Constitution requires that he or she get compensation.

Political or policy-oriented litigation is more prevalent in the appellate courts than in the trial courts and is most common in the U.S. Supreme Court. Ordinary compensatory litigation is often terminated early in the judicial process because the litigants find it more profitable to settle their dispute or accept the verdict of a trial court. However, litigants in political cases generally do little to advance their policy goals by gaining victories at the lower levels of the judiciary. Instead, they prefer the more widespread publicity that is attached to a decision by an appellate tribunal. Pursuing cases in the appellate courts is expensive. Therefore, many lawsuits that reach this level are supported in one way or another by interest groups.

INTEREST GROUPS IN THE JUDICIAL PROCESS

Although interest groups are probably better known for their attempts to influence legislative and executive branch decisions, they also pursue their policy goals in the courts. Some groups have found the judicial branch to be more receptive to their efforts than either of the other two branches of government. Interest groups that do not have the economic resources to mount an intensive lobbying effort in Congress or a state legislature may find it much easier to hire a lawyer and find some constitutional or statutory provision upon which to base a court case. Likewise, a small group with few registered voters among its members may lack the political clout to exert much influence on legislators and executive branch officials. Large memberships and political clout are not prerequisites for filing suits in the courts, however.

Interest groups may also turn to the courts because they find the judicial branch more sympathetic to their policy goals than the other two branches. Throughout the 1960s interest groups with liberal policy goals fared especially well in the federal courts. In addition, the public interest law firm concept gained prominence during this period. The public interest law firms pursue cases that serve the public interest in general – including cases in the areas of consumer rights, employment discrimination, occupational safety, civil liberties, and environmental concerns.

In the 1970s and 1980s conservative interest groups turned to the federal courts more frequently than they had before. This was in part a reaction to the successes of liberal interest groups. It was also due to the increasingly favorable forum that the federal courts provided for conservative viewpoints.

Interest group involvement in the judicial process may take several different forms depending upon the goals of the particular group. However, two principal tactics stand out: involvement in test cases and presentation of information before the courts through "amicus curiae" (Latin, meaning "friend of the court") briefs.

Test Cases

Because the judiciary engages in policy making only by rendering decisions in specific cases, one tactic of interest groups is to make sure that a case appropriate for obtaining its policy goals is brought before the court. In some instances this means that the interest group will initiate and sponsor the case by providing all the necessary resources. The best-known example of this type of sponsorship is Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In that case, although the suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, was filed by the parents of Linda Brown, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) supplied the legal help and money necessary to pursue the case all the way to the Supreme Court. Thurgood Marshall, who later became a U.S. Supreme Court justice, argued the suit on behalf of the plaintiff and the NAACP. As a result, the NAACP gained a victory through the Supreme Court's decision that segregation in the public schools violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Interest groups may also provide assistance in a case initiated by someone else, but which nonetheless raises issues of importance to the group. A good example of this situation may be found in a freedom of religion case, Wisconsin v. Yoder. That case was initiated by the state of Wisconsin when it filed criminal complaints charging Jonas Yoder and others with failure to send their children to school until the age of 16 as required by state law. Yoder and the others, members of the Amish faith, believed that education beyond the eighth grade led to the breakdown of the values they cherished and to "worldly influences on their children."

An organization known as the National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom (NCARF) came to the defense of Yoder and the others. Following a decision against the Amish in the trial court, the NCARF appealed to a Wisconsin circuit court, which upheld the trial court's decision. An appeal was made to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the Amish, saying that the compulsory school attendance law violated the free exercise of religion clause of the First Amendment. Wisconsin then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which on May 15, 1972, sustained the religious objection that the NCARF had raised to the compulsory school attendance laws.

As these examples illustrate, interest group involvement in litigation has focused on cases concerning major constitutional issues that have reached the Supreme Court. Because only a small percentage of cases ever reaches the nation's highest court, however, most of the work of interest group lawyers deals with more routine work at the lower levels of the judiciary. Instead of fashioning major test cases for the appellate courts, these attorneys may simply be required to deal with the legal problems of their groups' clientele.

During the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, for example, public interest lawyers not only litigated major civil rights questions; they also defended African Americans and civil rights workers who ran into difficulties with the local authorities. These interest group attorneys, then, performed many of the functions of a specialized legal aid society: They provided legal representation to those involved in an important movement for social change. Furthermore, they performed the important function of drawing attention to the plight of African Americans by keeping cases before the courts.

Amicus Curiae Briefs

Submission of amicus curiae briefs is the easiest method by which interest groups can become involved in cases. This method allows a group to get its message before the court even though it does not control the case. Provided it has the permission of the parties to the case or the permission of the court, an interest group may submit an amicus brief to supplement the arguments of the parties. The filing of amicus briefs is a tactic used in appellate rather than trial courts, at both the federal and the state levels.

Sometimes these briefs are aimed at strengthening the position of one of the parties in the case. When the Wisconsin v. Yoder case was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, the cause of the Amish was supported by amicus curiae briefs filed by the General Conference of Seventh Day Adventists, the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States, the Synagogue Council of America, the American Jewish Congress, the National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs, and the Mennonite Central Committee.

Sometimes friend-of-the-court briefs are used not to strengthen the arguments of one of the parties but to suggest to the court the group's own view of how the case should be resolved. Amicus curiae briefs are often filed in an attempt to persuade an appellate court to either grant or deny review of a lower-court decision. A study of the U.S. Supreme Court found that the presence of amicus briefs significantly increased the chances that the Court would give full treatment to a case.

Unlike private interest groups, all levels of the government can submit amicus briefs without obtaining permission. The solicitor general of the United States is especially important in this regard, and in some instances the Supreme Court may invite the solicitor general to present an amicus brief.

[Chapters 1 through 8 are adapted with permission from the book Judicial Process in America, 5th edition, by Robert A. Carp and Ronald Stidham, published by Congressional Quarterly, Inc. Copyright © 2001 Congressional Quarterly Inc. All rights reserved.]

Share this page