In 1953, Iran. U.S., and U.K. governments support shah's coup against Iran's Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh.

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, known in Iran as the 28 Mordad coup, was the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Iran, and its head of government Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh on 19 August 1953, orchestrated by the United Kingdom (under the name 'Operation Boot') and the United States (under the name TPAJAX Project).[3][4][5]

Mossadegh had sought to reduce the semi-absolute role of the Shah granted by the Constitution of 1906, thus making Iran a full democracy, as well as nationalizing the Iranian oil industry, which was controlled by the British owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, or AIOC (currently known as BP).[6][7]

[8] The coup saw the formation of a military government under General Fazlollah Zahedi, which allowed Mohammad-Rezā Shāh Pahlavi the Shah of Iran (Farsi for an Iranian king)[8] to effectively rule the country as an absolute monarch according to the constitution, relying heavily on United States support to hold on to power until his own overthrow in February 1979.[6][7][8][9] In August 2013 the CIA formally admitted that it was involved in both the planning and the execution of the coup, including the bribing of Iranian politicians, security and army high-ranking officials, as well as pro-coup propaganda.[10][11] The CIA is quoted acknowledging the coup was carried out "under CIA direction" and "as an act of U.S. foreign policy, conceived and approved at the highest levels of government." [12]

In 1951, Iran's oil industry was nationalized with near-unanimous support of Iran's parliament in a bill introduced by Mossadegh who led the nationalist party the National Front. Iran's oil had been controlled by the British-owned AIOC prior to this occasion.[13] Popular discontent with the AIOC began in the late 1940s: a large segment of Iran's public and a number of politicians saw the company as exploitative and a central tool of continued British imperialism in Iran.[6][14] Despite Mosaddegh's popular support, Britain was unwilling to negotiate on its single most valuable foreign asset, and instigated a worldwide boycott of Iranian oil to pressure Iran economically.[15] Initially, Britain mobilized its military to seize control of the Abadan oil refinery, then the world's largest, but Prime Minister Clement Attlee opted instead to tighten the economic boycott[16] while using Iranian agents to undermine Mosaddegh's government.[17] With a change to more conservative governments in both Britain and the United States, Churchill and the Eisenhower administration decided to overthrow Iran's government though the predecessor Truman administration had opposed a coup.[18] Classified documents show British intelligence officials played a pivotal role in initiating and planning the coup,and that AIOC (now BP) contributed $25,000 towards the expense of bribing officials.[19]

Britain and the U.S. selected Fazlollah Zahedi to be the prime minister of a military government that was to replace Mosaddegh as premier. Subsequently, a royal decree dismissing Mosaddegh and appointing Zahedi was drawn up by the coup plotters and signed by the Shah. The Central Intelligence Agency had successfully pressured the weak monarch to participate in the coup, while bribing street thugs, clergy, politicians and Iranian army officers to take part in a propaganda campaign against Mosaddegh and his government.[20] At first, the coup appeared to be a failure when on the night of 15–16 August, Imperial Guard Colonel Nematollah Nassiri was arrested while attempting to arrest Mosaddegh. The Shah fled the country the next day. On 19 August, a pro-Shah mob paid by the CIA, marched on Mosaddegh's residence.[21] According to the CIA's declassified documents and records, some of the most feared mobsters in Tehran were hired by the CIA to stage pro-Shah riots on 19 August. Other CIA-paid men were brought into Tehran in buses and trucks, and took over the streets of the city.[22] Between 300[1] and 800 people were killed because of the conflict.[2] Mosaddegh was arrested, tried and convicted of treason by the Shah's military court. On 21 December 1953, he was sentenced to three years in jail, then placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life.[23][24][25] Other Mosaddegh supporters were imprisoned, and several received the death penalty.[8]

After the coup, the Shah ruled as an absolute monarch for the next 26 years (under what he called a "guided democracy")[7][8] while significantly modernizing the country using oil revenue, until he was overthrown in the Iranian Revolution in 1979.[7][8][26] The tangible benefits the United States reaped from overthrowing Iran's elected government included a share of Iran's oil wealth[27][clarification needed] as well as resolute prevention of the possibility that the Iranian government might align itself with the Soviet Union, although the latter motivation produces controversy among historians. Washington continually supplied arms to the increasingly unpopular Shah and the CIA-trained SAVAK, his repressive secret police force;[8] however by the 1979 revolution, his increasingly independent policies resulted in his effective abandonment by his American allies, hastening his downfall.[28] The coup is widely believed to have significantly contributed to anti-American sentiment in Iran and the Middle East. The 1979 revolution deposed the Shah and replaced the pro-Western absolute monarchy with the largely anti-Western authoritarian theocracy.[29][30]

U.S. role

As a condition for restoring the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, in 1954 the U.S. required removal of the AIOC's monopoly; five American petroleum companies, Royal Dutch Shell, and the Compagnie Française des Pétroles, were to draw Iran's petroleum after the successful coup d'état—Operation Ajax. The Shah declared this to be a "victory" for Iranians, with the massive influx of money from this agreement resolving the economic collapse from the last three years, and allowing him to carry out his planned modernization projects.[8]

As part of that, the CIA organized anti-Communist guerrillas to fight the Tudeh Party if they seized power in the chaos of Operation Ajax.[70] Per released National Security Archive documents, Undersecretary of State Walter Bedell Smith reported that the CIA had agreed with Qashqai tribal leaders, in south Iran, to establish a clandestine safe haven from which U.S.-funded guerrillas and spies could operate.[70][71]

Operation Ajax's formal leader was senior CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt, Jr., while career agent Donald Wilber was the operational leader, planner, and executor of the deposition of Mosaddegh. The coup d'état depended on the impotent Shah's dismissing the popular and powerful Prime Minister and replacing him with General Fazlollah Zahedi, with help from Colonel Abbas Farzanegan—a man agreed upon by the British and Americans after determining his anti-Soviet politics.[71]

The CIA sent Major General Norman Schwarzkopf, Sr. to persuade the exiled Shah to return to rule Iran. Schwarzkopf trained the security forces that would become known as SAVAK to secure the shah's hold on power.[72]

The coup and CIA records

The coup was carried out by the U.S. administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower in a covert action advocated by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and implemented under the supervision of his brother Allen Dulles, the Director of Central Intelligence.[73] The coup was organized by the United States' CIA and the United Kingdom's MI6, two spy agencies that aided royalists and royalist elements of the Iranian army.[74] Much of the money was channeled through the pro-Shah Ayatollah Mohammad Behbahani, who drew many religious masses to the plot. Ayatollah Kashani had completely turned on Mossadegh and supported the Shah, by this point.[6]

According to a heavily redacted CIA document[75] released to the National Security Archive in response to a Freedom of Information request, "Available documents do not indicate who authorized CIA to begin planning the operation, but it almost certainly was President Eisenhower himself. Eisenhower biographer Stephen Ambrose has written that the absence of documentation reflected the President's style."

The CIA document then quotes from the Ambrose biography of Eisenhower:

Before going into the operation, Ajax had to have the approval of the President. Eisenhower participated in none of the meetings that set up Ajax; he received only oral reports on the plan; and he did not discuss it with his Cabinet or the NSC. Establishing a pattern he would hold to throughout his Presidency, he kept his distance and left no documents behind that could implicate the President in any projected coup. But in the privacy of the Oval Office, over cocktails, he was kept informed by Foster Dulles, and he maintained a tight control over the activities of the CIA.[76]

CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt, Jr., the grandson of former President Theodore Roosevelt, carried out the operation planned by CIA agent Donald Wilber. One version of the CIA history, written by Wilber, referred to the operation as TPAJAX.[77][78]

Shaban Jafari, commonly known as Shaban the Brainless (Shaban Bimokh), was a notable pro-Shah strongman and thug. He led his men and other bribed street thugs and was a prominent figure during the coup.

During the coup, Roosevelt and Wilber, representatives of the Eisenhower administration, bribed Iranian government officials, reporters, and businessmen. They also bribed street thugs to support the Shah and oppose Mosaddegh.[79] The deposed Iranian leader, Mosaddegh, was taken to jail and Iranian General Fazlollah Zahedi named himself prime minister in the new, pro-western government.

Another tactic Roosevelt admitted to using was bribing demonstrators into attacking symbols of the Shah, while chanting pro-Mossadegh slogans. As king, the Shah was largely seen as a symbol of Iran at the time by many Iranians and monarchists. Roosevelt declared that the more that these agents showed their hate for the Shah and attacked his symbols, the more it caused regular people to dislike and distrust Mossadegh.[80]

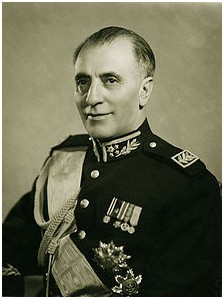

Fazlollah Zahedi

Professor Masoud Kazemzadeh wrote that several "Iranian fascists and Nazi sympathizers played prominent roles in the coup regime. General Fazlollah Zahedi, who had been arrested and imprisoned by the British during World War II for his attempt to establish a pro-Nazi government, was made Prime Minister on 19 August 1953. The CIA gave Zahedi about $100,000 before the coup and an additional $5 million the day after the coup to help consolidate support for the coup."[81] Kazemzadeh also said "Bahram Shahrokh, a trainee of Joseph Goebbels and Berlin Radio's Farsi program announcer during the Nazi rule, became director of propaganda. Mr. Sharif-Emami, who also had spent some time in jail for his pro-Nazi activities in the 1940s, assumed several positions after 1953 coup, including Secretary General of the Oil Industry, President of the Senate, and Prime Minister (twice)."[81] The US government gave Zahedi a further $28 million a month later, and that another $40 million was given in 1954 after the Iran government signed the oil consortium deal.[82]

The British and American spy agencies returned the monarchy to Iran by installing the pro-western Mohammad Reza Pahlavi on the throne where his rule lasted 26 years. The Shah was overthrown in 1979.[44][83] Masoud Kazemzadeh, associate professor of political science at the Sam Houston State University, wrote that the Shah was directed by the CIA and MI6, and assisted by high-ranking Shia clerics.[81] He wrote that the coup employed mercenaries including "prostitutes and thugs" from Tehran's red light district.[81]

The overthrow of Iran's elected government in 1953 ensured Western control of Iran's petroleum resources and prevented the Soviet Union from competing for Iranian oil.[84][85][86][87] Some Iranian clerics cooperated with the western spy agencies because they were dissatisfied with Mosaddegh's secular government.[79]

While the broad outlines of the operation are known, "the C.I.A.'s records were widely thought by historians to have the potential to add depth and clarity to a famous but little-documented intelligence operation," reporter Tim Weiner wrote in The New York Times 29 May 1997.[88]

"The Central Intelligence Agency, which has repeatedly pledged for more than five years to make public the files from its secret mission to overthrow the government of Iran in 1953, said today that it had destroyed or lost almost all the documents decades ago."[88][89][90]

"A historian who was a member of the C.I.A. staff in 1992 and 1993 said in an interview today that the records were obliterated by 'a culture of destruction' at the agency. The historian, Nick Cullather, said he believed that records on other major cold war covert operations had been burned, including those on secret missions in Indonesia in the 1950s and a successful C.I.A.-sponsored coup in Guyana in the early 1960s. 'Iran—there's nothing', Mr. Cullather said. 'Indonesia—very little. Guyana—that was burned.'"[88]

Donald Wilber, one of the CIA officers who planned the 1953 coup in Iran, wrote an account titled, Clandestine Service History Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran: November 1952 – August 1953. Wilber said one goal of the coup was to strengthen the Shah.

In 2000, James Risen at The New York Times obtained the previously secret CIA version of the coup written by Wilber and summarized[91] its contents, which includes the following.

In early August, the C.I.A. stepped up the pressure. Iranian operatives pretending to be Communists threatened Muslim leaders with savage punishment if they opposed Mossadegh, seeking to stir anti-Communist sentiment in the religious community. In addition, the secret history says, the house of at least one prominent Muslim was bombed by C.I.A. agents posing as Communists. It does not say whether anyone was hurt in this attack. The agency was also intensifying its propaganda campaign. A leading newspaper owner was granted a personal loan of about $45,000, in the belief that this would make his organ amenable to our purposes. But the shah remained intransigent. In an 1 August meeting with General Norman Schwarzkopf, he refused to sign the C.I.A.-written decrees firing Mr. Mossadegh and appointing General Zahedi. He said he doubted that the army would support him in a showdown.

The National Security Archive at George Washington University contains the full account by Wilber, along with many other coup-related documents and analysis.[92][93][94]

In a January 1973 telephone conversation made public in 2009, U.S. President Richard Nixon told CIA Director Richard Helms, who was awaiting Senate confirmation to become the new U.S. Ambassador to Iran, that Nixon wanted Helms to be a "regional ambassador" to Persian Gulf oil states, and noted that Helms had been a schoolmate of Shah Reza Pahlavi.[95]

In August 2013, at the sixtieth anniversary of the coup, the CIA released documents showing they were involved in staging the coup. The documents also describe the motivations behind the coup and the strategies used to stage it.[5] The documents also showed that the UK tried to censor information regarding its role in the coup. The Foreign Office said "it could neither confirm nor deny Britain's involvement in the coup". Nonetheless, many CIA documents about the coup still remain classified.[11]

U.S. motives

Historians disagree on what motivated the United States to change its policy towards Iran and stage the coup. Middle East historian Ervand Abrahamian identified the coup d'état as "a classic case of nationalism clashing with imperialism in the Third World". He states that Secretary of State Dean Acheson admitted the "'Communist threat' was a smokescreen" in responding to President Eisenhower's claim that the Tudeh party was about to assume power.[96]

Throughout the crisis, the "communist danger" was more of a rhetorical device than a real issue—i.e. it was part of the cold-war discourse.The Tudeh was no match for the armed tribes and the 129,000-man military. What is more, the British and Americans had enough inside information to be confident that the party had no plans to initiate armed insurrection. At the beginning of the crisis, when the Truman administration was under the impression a compromise was possible, Acheson had stressed the communist danger, and warned if Mosaddegh was not helped, the Tudeh would take over. The (British) Foreign Office had retorted that the Tudeh was no real threat. But, in August 1953, when the Foreign Office echoed the Eisenhower administration's claim that the Tudeh was about to take over, Acheson now retorted that there was no such communist danger. Acheson was honest enough to admit that the issue of the Tudeh was a smokescreen.[96]

Abrahamian states that Iran's oil was the central focus of the coup, for both the British and the Americans, though "much of the discourse at the time linked it to the Cold War".[97] Abrahamian wrote, "If Mosaddegh had succeeded in nationalizing the British oil industry in Iran, that would have set an example and was seen at that time by the Americans as a threat to U.S. oil interests throughout the world, because other countries would do the same."[97] Mosaddegh did not want any compromise solution that allowed a degree of foreign control. Abrahamian said that Mosaddegh "wanted real nationalization, both in theory and practice".[97]

Tirman points out that agricultural land owners were politically dominant in Iran, well into the 1960s and the monarch, Reza Shah's aggressive land expropriation policies—to the benefit of himself and his supporters—resulted in the Iranian government being Iran's largest land owner. "The landlords and oil producers had new backing, moreover, as American interests were for the first time exerted in Iran. The Cold War was starting, and Soviet challenges were seen in every leftist movement. But the reformers were at root nationalists, not communists, and the issue that galvanized them above all others was the control of oil."[98] The belief that oil was the central motivator behind the coup has been echoed in the popular media by authors such as Robert Byrd,[99] Alan Greenspan,[100] and Ted Koppel.[101]

However, Middle East political scientist Mark Gasiorowski states that while, on the face of it, there is considerable merit to the argument that U.S. policymakers helped U.S. oil companies gain a share in Iranian oil production after the coup, "it seems more plausible to argue that U.S. policymakers were motivated mainly by fears of a communist takeover in Iran, and that the involvement of U.S. companies was sought mainly to prevent this from occurring. The Cold War was at its height in the early 1950s, and the Soviet Union was viewed as an expansionist power seeking world domination. Eisenhower had made the Soviet threat a key issue in the 1952 elections, accusing the Democrats of being soft on communism and of having 'lost China.' Once in power, the new administration quickly sought to put its views into practice."[52]

Gasiorowski further states "the major U.S. oil companies were not interested in Iran at this time. A glut existed in the world oil market. The U.S. majors had increased their production in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in 1951 in order to make up for the loss of Iranian production; operating in Iran would force them to cut back production in these countries which would create tensions with Saudi and Kuwaiti leaders. Furthermore, if nationalist sentiments remained high in Iran, production there would be risky. U.S. oil companies had shown no interest in Iran in 1951 and 1952. By late 1952, the Truman administration had come to believe that participation by U.S. companies in the production of Iranian oil was essential to maintain stability in Iran and keep Iran out of Soviet hands. In order to gain the participation of the major U.S. oil companies, Truman offered to scale back a large anti-trust case then being brought against them. The Eisenhower administration shared Truman's views on the participation of U.S. companies in Iran and also agreed to scale back the anti-trust case. Thus, not only did U.S. majors not want to participate in Iran at this time, it took a major effort by U.S. policymakers to persuade them to become involved."[52]

In 2004, Gasiorowski edited a book on the coup[102] arguing that "the climate of intense cold war rivalry between the superpowers, together with Iran's strategic vital location between the Soviet Union and the Persian Gulf oil fields, led U.S. officials to believe that they had to take whatever steps were necessary to prevent Iran from falling into Soviet hands."[102] While "these concerns seem vastly overblown today"[102] the pattern of "the 1945–46 Azerbaijan crisis, the consolidation of Soviet control in Eastern Europe, the communist triumph in China, and the Korean War—and with the Red Scare at its height in the United States"[102] would not allow U.S. officials to risk allowing the Tudeh Party to gain power in Iran.[102]

Furthermore, "U.S. officials believed that resolving the oil dispute was essential for restoring stability in Iran, and after March 1953 it appeared that the dispute could be resolved only at the expense either of Britain or of Mosaddeq."[102] He concludes "it was geostrategic considerations, rather than a desire to destroy Mosaddeq's movement, to establish a dictatorship in Iran or to gain control over Iran's oil, that persuaded U.S. officials to undertake the coup."[102]

Faced with choosing between British interests and Iran, the U.S. chose Britain, Gasiorowski said. "Britain was the closest ally of the United States, and the two countries were working as partners on a wide range of vitally important matters throughout the world at this time. Preserving this close relationship was more important to U.S. officials than saving Mosaddeq's tottering regime." A year earlier, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill used Britain's support for the U.S. in the Cold War to insist the United States not undermine his campaign to isolate Mosaddegh. "Britain was supporting the Americans in Korea, he reminded Truman, and had a right to expect 'Anglo-American unity' on Iran."[103]

The two main winners of World War II, who had been Allies during the war, became superpowers and competitors as soon as the war ended, each with their own spheres of influence and client states. After the 1953 coup, Iran became one of the client states of the United States. In his earlier book, U.S. Foreign Policy and the Shah: Building a Client State in Iran, Gasiorowski identifies the client states of the United States and of the Soviet Union during 1954–1977. Gasiorowski identified Cambodia, Guatemala, Indonesia, Iran, Laos, Nicaragua, Panama, the Philippines, South Korea, South Vietnam, and Taiwan as strong client states of the United States and identified those that were moderately important to the U.S. as Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Greece, Haiti, Honduras, Israel, Jordan, Liberia, Pakistan Paraguay, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, and Zaire. He named Argentina, Chile, Ethiopia, Japan, and Peru as "weak" client states of the United States.[104]

Gasiorowski identified Bulgaria, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Mongolia Poland, North Vietnam, and Rumania as "strong client states" of the Soviet Union, and Afghanistan Egypt, Guinea, North Korea, Somalia, and Syria as moderately important client states. Mali and South Yemen were classified as weak client states of the Soviet Union.

According to Kinzer, for most Americans, the crisis in Iran became just part of the conflict between Communism and "the Free world".[105] "A great sense of fear, particularly the fear of encirclement, shaped American consciousness during this period. ... Soviet power had already subdued Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia. Communist governments were imposed on Bulgaria and Romania in 1946, Hungary and Poland in 1947, and Czechoslovakia in 1948. Albania and Yugoslavia also turned to communism. Greek communists made a violent bid for power. Soviet soldiers blocked land routes to Berlin for sixteen months. In 1949, the Soviet Union successfully tested a nuclear weapon. That same year, pro-Western forces in China lost their civil war to communists led by Mao Zedong. From Washington, it seemed that enemies were on the march everywhere."[105] Consequently, "the United States, challenged by what most Americans saw as a relentless communist advance, slowly ceased to view Iran as a country with a unique history that faced a unique political challenge."[106] Some historians, including Douglas Little,[107] Abbas Milani[108] and George Lenczowski[109] have echoed the view that fears of a communist takeover or Soviet influence motivated the U.S. to intervene.

Shortly before the overthrow of Mossadegh, Adolf A. Berle warned the U.S. State Department that U.S. "control of the Middle East was at stake, which, with its Persian Gulf oil, meant 'substantial control of the world.'"[110]