War in Afghanistan (2001–present)

USINFO | 2013-09-16 14:04

The War in Afghanistan (2001–present) refers to the intervention in the Afghan Civil War by the United States and its allies, following theterrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, to dismantle Al-Qaeda, the Islamic terrorist organization led by Osama bin Laden and to remove from power the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist regime led by Mullah Mohammed Omar, which at the time controlled 90% of Afghanistan and hosted Al-Qaeda leadership. U.S. President George W. Bush demanded that the Taliban hand over bin Laden and al-Qaeda leadership which was supporting the Taliban in its war with the Northern Alliance. The Taliban recommended that bin Laden leave the country but declined to extradite him without evidence of his involvement in the 9/11 attacks. The United States refused to negotiate and launched Operation Enduring Freedom on 7 October 2001 with theUnited Kingdom and Italy, later joined by Russia, France, Australia, Canada, Poland, Germany and other mainly western allies, to attack the Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces in conjunction with the Northern Alliance.[22][23]

The U.S. and its allies quickly drove the Taliban from power and captured all major cities and towns in the country. Many Al Qaeda and Taliban leaders escaped to neighboring Pakistan or retreated to rural or remote mountainous regions. In December 2001, the U.N. Security Councilestablished the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), to oversee security in the country and train the Afghan National Army. At the Bonn Conference in December 2001, Hamid Karzai was selected to head the Afghan Interim Administration, which after a loya jirga in Kabul in June 2002, became the Afghan Transitional Administration. In the popular elections of 2004, Karzai was elected the president of the new permanent Afghan government, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.[24]

In 2003, NATO assumed leadership of ISAF, included troops from 43 countries, with NATO members providing the core of the force.[25] Only a portion of U.S. forces in Afghanistan operate under NATO command; the rest remained under direct American command. Mullah Omar reorganized the Taliban movement and launched the insurgency against the Afghan government and ISAF forces in the spring of 2003.[26][27] Though vastly outgunned and outnumbered by NATO forces and the Afghan National Army, the Taliban and its allies, most notably the Haqqani Network and Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin, have waged asymmetric warfare with guerilla raids and ambushes in the countryside, suicide attacks against urban targets, and turncoat killings against coalition forces. The Taliban exploited the weak administration of the Afghan government, among the most corrupt in the world, to reassert influence across rural areas of southern and eastern Afghanistan. NATO countries responded in 2006 by increasing troops for operations to "clear and hold" villages and "nation building" projects to "win hearts and minds".[28][29]

While NATO forces continued to battle the Taliban insurgency, the war expanded into the tribal areas of neighboring North-West Pakistan.[30] In 2004, the Pakistani Army began to clash with local tribes hosting Al-Qaeda and Taliban forces. The U.S. military began to launch air strikes and then drone strikes into the region, targeting at first Al-Qaeda and later the local "Pakistan Taliban" leaders, which launched an insurgency in Waziristan in 2007.

On 2 May 2011, U.S. forces killed Osama bin Laden in Abbotabad, Pakistan. On 21 May 2012 the leaders of the NATO-member countries endorsed an exit strategy for removing NATO soldiers from Afghanistan.

Tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians have lost their lives in the war.[31]

The breakdown of Afghanistan's political order began with the overthrow of King Zahir Shah by his cousin Mohammed Daoud Khan in a bloodless coup in 1973. Daoud Khan, who had served as prime minister since 1953, continued to promote economic modernization, emanicipation of women and Pashtun nationalism, which was threatening to neighboring Pakistan, with its own restive Pashtun population. In the mid-1970s, Pakistani Prime MinisterZulfikar Ali Bhutto began to encourage Islamic leaders from Afghanistan such as Burhanuddin Rabbani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, to fight against the Daoud Khan regime. In 1978, Daoud Khan was killed in a coup by Afghan's Communist Party, his former partner in government, known as the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The PDPA pushed for socialist transformation of Afghan society by abolishing arranged marriages, promoting mass literacy and reforming land ownership, which undermined the traditional tribal order and provoked opposition from Islamic leaders across rural areas of the country. The PDPA's crackdown was met with open rebellion, including Ismail Khan's Herat Uprising. The PDPA itself was beset by leadership differences and weakened by another an internal coup on September 11, 1979 when Hafizullah Amin ousted Nur Muhammad Taraki. The Soviet Union, sensing PDPA weakness, intervened militarily three months later, to depose Amin and install another PDA faction led by Babrak Karmal.

After the withdrawal of the Soviet military from Afghanistan in May 1989, the PDPA regime under Najibullah held on against the Mujahedeein until 1992 when the collapse of the Soviet Union deprived the regime of aid, and the defection of Uzbek general Abdul Rashid Dostum cleared the approach to Kabul. With the political stage cleared of Afghan socialists, the remaining Islamic warlords vied for power. By then Bin Laden had left the country. The United States' interest in Afghanistan also diminished.

Warlord Interregnum (1992-1996)

Main article: Civil war in Afghanistan (1992–96)

In 1992, Rabbani became president of the Islamic State of Afghanistan but this regime fought with other warlords for control of Kabul. In late 1994, Rabbani's defense minister, Ahmad Shah Massoud defeated Hekmatyr in Kabul and ended bombardments of the capital.[32][33][34] Massoud tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation. Other warlords maintained their fiefdoms such as Ismail Khan in the west and Dostum in the north.

In 1994, Mullah Omar, a Pashtun mujahedeen, who taught at a madrassa in Pakistan, returned to Kandahar and founded the Taliban. His followers were religious students, known as the Talib and they sought to end warlordism through strict adherence to Islamic law. By November 1994, the Taliban had captured all of Kandahar Province. They declined the government's offer to join in a coalition government and marched on Kabul in 1995.[35] The Taliban declined.[35]

Taliban Emirate vs Northern Alliance

The Taliban's early victories in 1994 were followed by a series of defeats that resulted in heavy losses.[36] Pakistan provided strong support to the Taliban.[37][38] Analysts such as Amin Saikal described the Taliban as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests, which the Taliban deny.[37] The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were driven by back by Massoud.[33][39]

Former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf sent thousands of Pakistani troops to fight with the Taliban and Bin Laden against the forces of Massoud.

On 27 September 1996, the Taliban, with military support by Pakistan and financial support by Saudi Arabia, seized Kabul and founded the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.[40] They imposed their fundamentalist interpretation of Islam in areas under their control, issuing edicts forbidding women to work outside the home, attend school, or to leave their homes unless accompanied by a male relative.[41] According to the Pakistani expert Ahmed Rashid, "between 1994 and 1999, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Pakistanis trained and fought in Afghanistan" on the side of the Taliban.[42][43]

Massoud and Dostum, former arch-enemies, created a United Front, commonly known as the Northern Alliance against the Taliban.[44] In addition to the Tajik forces of Massoud and the Uzbek forces of Dostum, the United Front included Hazara factions and Pashtun forces under the leadership of commanders such as Abdul Haq and Haji Abdul Qadir. Abdul Haq received a limited number of defecting Pashtun Taliban.[45] Both agreed to work together with the exiled Afghan king Zahir Shah.[43] International officials who met with representatives of the new alliance, which the journalistSteve Coll referred to as the "grand Pashtun-Tajik alliance", said, "It's crazy that you have this today ... Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Hazara ... They were all ready to buy in to the process ... to work under the king's banner for an ethnically balanced Afghanistan."[46][47] The Northern Alliance received varying degrees of support from Russia, Iran, Tajikistan and India.

The Taliban captured Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998 and drove Dostum went into exile.

The conflict was brutal. According the United Nations (UN), the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians.[48][49] UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001.[48][49] The Taliban especially targeted the Shiite Hazaras.[48][49] In retaliation of the execution of 3,000 Taliban prisoners by Uzbek general Abdul Malik Pahlawan in 1997, the Taliban executed about 4,000 civilians after taking Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998.[50][51]

Bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians.[52] The report by the United Nations quotes eyewitnesses in many villages describing "Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people".[48][49]

By 2001, the Taliban controlled as much as 90% of the country, with the Northern Alliance confined to northeast corner of Afghanistan. Fighting alongside Taliban forces were some 28,000-30,000 Pakistanis and 2,000-3,000 Al Qaeda militants.[35][52][53][54] Many of the Pakistanis were recruited from madrassas.[52] A 1998 document by the U.S. State Department confirmed that "20–40 percent of [regular] Taliban soldiers are Pakistani."[38] The document said that many of the parents of those Pakistani nationals "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan."[38] According to the U.S. State Department report and reports by Human Rights Watch, the other Pakistani nationals fighting in Afghanistan were regular soldiers, especially from the Frontier Corps, but also from the army providing direct combat support.[38][55]

Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan

In August 1996, Osama Bin Laden was forced to leave Sudan and arrived in Jalabad, Afghanistan. He had founded Al-Qaeda in the late 1980s to support the mujahdeen's war against the Soviets but became disillusioned by infighting among warlords. He grew close to Mullah Omar and moved Al Qaeda's operations to eastern Afghanistan.

The 9/11 Commission in the US reported found that under the Taliban, al-Qaeda was able to use Afghanistan as a place to train and indoctrinate fighters, import weapons, coordinate with other jihadists, and plot terrorist actions.[56] While al-Qaeda maintained its own camps in Afghanistan, it also supported training camps of other organizations. An estimated 10,000 and 20,000 men passed through these facilities before 9/11, most of whom were sent to fight for the Taliban against the United Front. A smaller number were inducted into al-Qaeda.[57]

After the August 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings were linked to bin Laden, President Bill Clinton ordered missile strikes on militant training camps in Afghanistan. U.S. officials pressed the Taliban to surrender bin Laden. In 1999, the international community imposed sanctions on the Taliban, calling for bin Laden to be surrendered. The Taliban repeatedly rebuffed their demands.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Special Activities Division paramilitary teams were active in Afghanistan in the 1990s in clandestine operations to locate and kill or capture Osama bin Laden. These teams planned several operations but did not receive the order to execute from President Clinton.[58] Their efforts built many of the relationships with Afghan leaders that proved essential in the 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan.[58]

Change in U.S. policy toward Afghanistan

During the Clinton administration, the U.S. tended to favor Pakistan and until 1998-1999 had no clear policy toward Afghanistan. In 1997, for instance, the U.S. State Department's Robin Raphel told Ahmad Shah Massoud to surrender to the Taliban. Massoud responded that, as long as he controlled an area the size of his hat, he would continue to defend it from the Taliban.[35] Around the same time, top foreign policy officials in the Clinton administration flew to northern Afghanistan to try to persuade the United Front not to take advantage of a chance to make crucial gains against the Taliban.[59][59] They insisted it was the time for a cease-fire and an arms embargo. At the time, Pakistan began a "Berlin-like airlift to resupply and re-equip the Taliban", financed with Saudi money.[59]

U.S. policy toward Afghanistan changed after the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings. Subsequently, Osama bin Laden was indicted for his involvement in the embassy bombings. In 1999 both the U.S. and the United Nations enacted sanctions against the Taliban via United Nations Security Council Resolution 1267, which demanded the Taliban surrender Osama bin Laden for trial in the U.S. and close all terrorist bases in Afghanistan.[60] The only collaboration between Massoud and the US at the time was an effort with the CIA to trace Osama bin Laden following the 1998 bombings.[61] The U.S. and the European Union provided no support to Massoud for the fight against the Taliban.

By 2001 the change of policy sought by CIA officers who knew Massoud was underway.[62] CIA lawyers, working with officers in the Near East Division and Counter-terrorist Center, began to draft a formal finding for President George W. Bush’s signature, authorizing a new covert action program in Afghanistan. It would be the first in a decade to seek to influence the course of the Afghan war in favor of Massoud.[46] Richard A. Clarke, chair of the Counter-Terrorism Security Group under the Clinton administration, and later an official in the Bush administration, allegedly presented a plan to incoming Bush administration official Condoleezza Rice in January 2001.

According to later reporting, a change in US policy was concluded in August 2001.[46] The Bush administration agreed on a plan to start giving support to the anti-Taliban forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud, who sought to create a democratic form of government in Afghanistan. A meeting of the Bush administration's top national security officials agreed that the Taliban would be presented in negotiations with a final ultimatum to hand over Osama bin Laden and other leading al-Qaeda operatives. If the Taliban refused, the US would provide covert military aid to anti-Taliban groups. If both those options failed, "the deputies agreed that the United States would seek to overthrow the Taliban regime through more direct action."[63]

Northern Alliance on the eve of 9/11

Ahmad Shah Massoud was the only leader of the United Front in Afghanistan. In the areas under his control, Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Declaration.[64] As a consequence, many civilians had fled during those years to areas under his control.[65][66] In total, estimates range up to one million people fleeing the Taliban.[67]

In late 2000, Massoud officially brought together this new alliance in a meeting in Northern Afghanistan to discuss "a Loya Jirga, or a traditional council of elders, to settle political turmoil in Afghanistan".[68] That part of the Pashtun-Tajik-Hazara-Uzbek peace plan did eventually develop. Among those in attendance was a Pashtun named Hamid Karzai.[69][70]

In early 2001, Massoud, with other ethnic leaders, addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, asking the international community to provide humanitarian help to the people of Afghanistan.(see video)[67] He said that the Taliban and al-Qaeda had introduced "a very wrong perception of Islam" and that without the support of Pakistan and Osama bin Laden, the Taliban would not be able to sustain their military campaign for up to a year.[67] On this visit to Europe, he warned that his intelligence had gathered information about a large-scale attack on U.S. soil being imminent.[71]

On 9 September 2001, Massoud was critically wounded in a suicide attack by two Arabs posing as journalists, who detonated a bomb hidden in their video camera during an interview in Khoja Bahauddin, in the Takhar Province of Afghanistan.[72][73] Massoud died in the helicopter taking him to a hospital. The funeral, held in a rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of mourning Afghans.

September 11, 2001 Attacks

On the morning of 11 September 2001, al-Qaeda carried out four coordinated attacks on U.S. soil. Four commercial passenger jet airliners were hijacked.[74][75] The hijackers intentionally crashed two of the airliners into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing everyone on board and thousands working in the buildings. Both buildings collapsed within two hours from fire damage related to the crashes, destroying nearby buildings and damaging others. The hijackers crashed a third airliner into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, just outsideWashington, D.C.. The fourth plane crashed into a field near Shanksville, in rural Pennsylvania, after some of its passengers and flight crew attempted to retake control of the plane, which the hijackers had redirected toward Washington, D.C to target the White House, or the U.S. Capitol. No flights had survivors.

Nearly 3,000 people, including the 19 hijackers, died in the attacks.[76] According to the New York State Health Department, 836 responders, including firefighters and police personnel, have died as of June 2009.[76]

The case for war

On 11 September, the Taliban's foreign minister, Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil, "denounce[d] the terrorist attack, whoever is behind it."[77] The following day, President Bush called the attacks more than just "acts of terror" but "acts of war" and resolved to pursue and conquer an "enemy" that would no longer be safe in "its harbors."[78] The Taliban ambassador to Pakistan, Abdul Salam Zaeef said on 13 September that the Taliban would consider extraditing bin Laden if there was solid evidence linking him to the attacks.[79] Though in 2004, Osama bin Laden eventually took responsibility for the 9/11 attacks, he denied having any involvement in a statement issued on September 17 and by interview on September 29.[80][81]

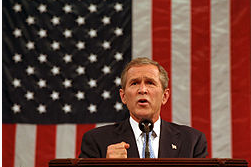

In an address to a joint-session of the U.S. Congress on 20 September 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush demanded that theTaliban deliver Osama bin Laden and destroy bases of Al-Qaeda. "They will hand over the terrorists or they will share in their fate," he said.[82]

The State Department, in a memo dated 14 September, demanded that the Taliban surrender all known al-Qaeda associates in Afghanistan, provide intelligence on him and his affiliates, and expel all terrorists from Afghanistan.[83] On 18 September, the director of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence, Mahmud Ahmedconveyed these demands to Mullah Omar and the senior Taliban leadership, whose response was "not negative on all points."[84] Mahmoud reported that the Taliban leadership was in "deep introspection" and waiting for the recommendation of a grand council of religious clerics that was assembling to decide the matter.[84] On 20 September, President Bush, in an address to Congress, demanded the Taliban deliver Osama bin Laden and destroy bases of al Qaeda.[85]

In the days and weeks immediately following 9/11, when the Taliban sought evidence of his involvement in the attacks, Osama bin Laden repeatedly denied having any role.

The same day, a grand council of over 1,000 Muslim clerics from across Afghanstan, which had convened at the request of the Taliban leadership to decide the fate of bin Laden, issued a fatwa, expressing sadness for the deaths in the 9/11 attacks, urging bin Laden to leave their country, and calling on theUnited Nations and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to conduct an independent investigation of "recent events to clarify the reality and prevent harassment of innocent people."[86] The fatwa went on to warn that should the United States not agree with its decision and invade Afghanistan, "jihad becomes an order for all Muslims."[86] White House spokesperson Ari Fleischer rejected the response, saying the time for talk had ended and it was time for action.[87]

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell toldMeet the Press on 23 September 2001, that the U.S. government would release evidence linking Osama bin Laden to the 9/11 attacks. The evidence, however, was not made public prior to the outbreak of war.

On 21 September, Taliban representatives in Pakistan reacted to the U.S. response with defiance.[88] Zaeef said the Taliban were ready, if necessary, for war with the United States.[88] His deputy Suhail Shaheen, warned that a U.S. invasion would share in the same fate that befell Great Britain and the Soviet Union in previous centuries.[88] Zaeef reiterated the demand for evidence of bin Laden's involvement in the 9/11 attacks.[88] "If the Americans provide evidence, we will cooperate with them, but they do not provide evidence," he said.[88] "In America, if I think you are a terrorist, is it properly justified that you should be punished without evidence?" he asked.[88] "This is an international principle. If you use the principle, why do you not apply it to Afghanistan?"[88] On 23 September, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell told NBC's Meet the Press that the U.S. government would, "in the near future" release "a document that will describe quite clearly the evidence . . . linking [bin Laden] to this attack."[89] The evidence was not made public but instead shown to Pakistan's government whose leaders later stated that the materials they had seen "provide[d] sufficient basis for indictment in a court of law."[90] Pakistan ISI chief Lieutenant General Mahmud Ahmed shared information provided to him by the U.S. with Taliban leaders.[91]

On 24 September, ISI Director Mahmoud told U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan that while the Taliban was "weak and ill-prepared to face the American onslaught", "real victory will come through negotiations" for if the Taliban were eliminated, Afghanistan would revert to warlordism.[92] On 28 September, he led a delegation of eight Pakistani religious leaders to persuade Mullah Omar to accept having religious leaders from Islamic countries examine the evidence and decide bin Laden's fate.[93] Mullah Omar was noncommittal.[93] The U.S. government remained opposed to any negotiations with the Taliban.[93]

Meanwhile the U.S. Department of Defense under Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, was exploring ways to broaden the military response beyond Afghanistan.[94] In a memo to President Bush on September 30, Rumsfeld argued "finding a few hundred terrorists in the caves of Afghanistan," was not the U.S. government's "strong suit" which should instead use "the vastness of our military and humanitarian resources," to strengthen the domestic opposition in "terrorist-supporting states" and achieve regime change in "Afghanistan and another key State (or two) that supports terrorism."[94]

On 30 September 2001, the U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeldurged a broader military response to the 9/11 attacks, going beyondregime change in Afghanistan to "another key State (or two) that support terrorism."

On 1 October, Mullah Omar agreed to a proposal by Qazi Hussain Ahmad, the head of Pakistan's most important Islamic party, the Jamaat-i-Islami, to have bin Laden taken to Pakistan where he would be held under house arrest in Peshawarand tried by an international tribunal.[95] But Pakistan's president Pervez Musharraf blocked the plan because he could not guarantee bin Laden's safety.[95] On 2 October, Zaeef appealed the United States to negotiate, "We do not want to compound the problems of the people, the country or the region."[96] He pleaded, "the Afghan people need food, need aid, need shelter, not war."[96] The U.S. government refused to negotiate and instead focused on building a new government around former Afghan King Zahir Shah.[96] The British Prime Minister Tony Blair called on the Taliban to "surrender the terrorists or surrender power."[97] Mullah Omar warned that unlike the former King's government which was overthrown in 1973 and surrendered, the Taliban "would just retreat to the mountains" and continue to fight.[96]

On 5 October, the Taliban offered to try bin Laden in an Afghan court, so long as the U.S. provided what it called "solid evidence" of his guilt.[98] The U.S. government dismissed the request for proof as "request for delay or prevarication"; NATO commander George Robertson said the evidence was "clear and compelling."[97] On 7 October, as the U.S. aerial bombing campaign began, President Bush ignored questions about the Taliban's offer and said instead "Full warning had been given, and time is running out."[99] The same day, the State Department gave the Pakistani government one last message to the Taliban: Hand over all al-Qaeda leaders or "every pillar of the Taliban regime will be destroyed."[100]

A week into the bombing campaign, on 14 October, Abdul Kabir, the Taliban's third ranking leader, offered to hand over bin Laden if the U.S. government provided evidence of his guilt and halted the bombing campaign. President Bush rejected the offer as non-negotiable.[101]On 16 October, Muttawakil, the Taliban foreign minister, dropped the condition to see evidence and offered to send bin Laden to a third country in return for a halt to the bombing.[102] US officials also rejected this offer.[103] At that time, some Afghan experts said the United States failed to recognize the Taliban's need for a "face saving formula."[104] In 2007, bin Laden indicated that the Taliban had no knowledge of his plans for the 9/11 attacks.[105]

Legal basis for war

On 14 September 2001, Congress passed legislation titled Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, which was signed on 18 September 2001 by President Bush. It authorized the use of U.S. Armed Forces against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks. The Bush administration, for its part, did not seek a declaration of war by Congress, and labeled Taliban troops as supporters of terrorists rather than soldiers. It thus defined them as outside the protections of the Geneva Convention and due process of law. This position was later overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2008, following other decisions that overturned some Bush executive positions in the war on terror.[106] Military lawyers responsible for prosecuting detainees also had questioned some of the policies, and such internal disagreements were revealed years later in the press.[107]

The United Nations Charter, to which all the Coalition countries are signatories, provides that all UN member states must settle their international disputes peacefully and no member nation can use military force except in self-defense. The U.S. Constitution states that international treaties, such as the United Nations Charter, that are ratified by the U.S. are part of the law of the land, though subject to effective repeal by any subsequent act of the U.S. Congress (i.e., the "leges posteriores priores contrarias abrogant" or "last in time" canon of statutory interpretation).[108] The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) did not authorize the U.S.-led military campaign in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom).

Defenders of the legitimacy of the U.S.-led invasion argue that U.N. Security Council authorization was not required since the invasion was an act of collective self-defense provided for under Article 51 of the UN Charter, and not a war of aggression.[108][109] Critics maintain that the bombing and invasion of Afghanistan were not legitimate self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter because the 9/11 attacks were not “armed attacks” by another state, but were perpetrated by non-state actors. They said these attackers had no proven connection to Afghanistan or the Taliban rulers. Such critics have said that, even if a state had made the 9/11 attacks, no bombing campaign would constitute self-defense. They interpreted self-defense to be actions that were "instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation."[108]

On 20 December 2001, more than two months after the U.S.-led attack began, the UNSC authorized the creation of an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to take all measures necessary to fulfill its mandate of assisting the Afghan Interim Authority in maintaining security.[110] Command of the ISAF passed to NATO on 11 August 2003, following the US invasion of Iraq in March of that year.[111]

History of the conflict

2001: Overthrow of the Taliban

On 7 October 2001, the U.S. government launched military operations in Afghanistan. On 7 October 2001, airstrikes were reported in Kabul (where electricity supplies were severed), at the airport, at Kandahar (home of the Taliban's Supreme Leader Mullah Omar), and in the city of Jalalabad. CNN released exclusive footage of Kabul being bombed to American broadcasters at approximately 5:08 pm 7 October 2001.[112]

U.S. Army Special Forces and U.S. Air Force Combat Controllers with Northern Alliance troops on horseback

On the ground, teams from the CIA's Special Activities Division (SAD) were the first U.S. forces to enter Afghanistan and begin combat operations. They were soon joined by U.S. Army Special Forces from the 5th Special Forces Group and other units fromUSSOCOM.[113][114]At 17:00 UTC, President Bush confirmed the strikes on national television and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Tony Blair also addressed the UK. Bush stated that Taliban military sites and terrorist training grounds would be targeted. In addition, food, medicine, and supplies would be dropped to "the starving and suffering men, women and children of Afghanistan".[116]

Bin Laden released a prerecorded videotape before the attacks in which he condemned any attacks against Afghanistan. Al Jazeera, the Arabic satellite news channel, reported that the tapes were received shortly before the attack.

British and American special forces worked jointly to take Herat in November 2001. These forces worked with Afghan opposition groups on the ground, in particular the Northern Alliance. The United Kingdom, Canada and Australia also deployed forces, and several other countries provided basing, access and overflight permission.

The U.S. was able to track Mohammed Atef, al-Qaeda's number three at the time, who was one of the most wanted. He was killed by bombing at his Kabul home between 14–16 November 2001, along with his guard Abu Ali al-Yafi'i and six others.[117][118] This was one of America's first and largest victories during the early stages of the war.

Air campaigns

Bombers operating at high altitudes well out of range of antiaircraft guns bombed at Afghan training camps and Taliban air defenses. U.S. aircraft, including Apache helicopter gunships from the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade, operated throughout the campaign with no losses due to Taliban air defenses. U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers launched several Tomahawk Cruise Missiles.

The strikes initially focused on the area in and around the cities of Kabul, Jalalabad, and Kandahar. Within a few days, most Taliban training sites were severely damaged, and the Taliban's air defenses were destroyed. The campaign focused on command, control, and communication targets, which weakened the ability of the Taliban forces to communicate. But, the line facing the Afghan Northern Alliance held, and no battlefield successes were achieved. Two weeks into the campaign, the Northern Alliance demanded the air campaign focus more on the front lines.

The next stage of the campaign began with carrier based F/A-18 Hornet fighter-bombers hitting Taliban vehicles in pinpoint strikes, while other U.S. planes began cluster bombing Taliban defenses. For the first time in years, Northern Alliance commanders began to see the substantive results that they had long hoped for on the front lines.

At the beginning of November, the allied forces attacked front lines with daisy cutter bombs, and by AC-130 gunships. The Taliban fighters had no previous experience with American firepower, and often stood on top of bare ridgelines where U.S. Army Special Forces could easily spot them and call in close air support. By 2 November, Taliban frontal positions were devastated, and a Northern Alliance march on Kabul seemed possible. According to author Stephen Tanner,

"After a month of the U.S. bombing campaign rumblings began to reach Washington from Europe, the Mideast, and Pakistan where Musharraf had requested the bombing to cease. Having begun the war with the greatest imaginable reservoir of moral authority, the U.S. was on the verge of letting it slip away through high-level attacks using the most ghastly inventions its scientists could come up with."[119]

President George W. Bush went to New York City on 10 November 2001, "where the wreckage of the World Trade Center still smoldered with underground fires",[119]to address the United Nations. He said that not only the U.S. was in danger of further attacks by the 9/11 terrorists, but so was every other countries in the world. Tanner writes: "His words had impact. Most of the world renewed its support for the American effort, including commitments of material help from Germany, France, Italy, Japan and other countries."[119]

Fighters from al-Qaeda took over security in the Afghan cities, demonstrating the instability of the Taliban regime. The Northern Alliance and their Central Intelligence Agency/Special Forces advisers planned the next stage of their offensive. Northern Alliance troops would seize Mazari Sharif, thereby cutting off Taliban supply lines and enabling the flow of equipment from the countries to the north, followed by an attack on Kabul itself.

Areas most targeted

During the early months of the war, the U.S. military had a limited presence on the ground. The plan was that Special Forces, and intelligence officers with a military background, would serve as liaisons with Afghan militias opposed to the Taliban, would advance after the cohesiveness of the Taliban forces was disrupted by American air power.[120][121][122]

The Tora Bora Mountains lie roughly east of Afghanistan's capital Kabul, which is close to the border with Pakistan. American intelligence analysts believed that the Taliban and al-Qaeda had dug in behind fortified networks of well-supplied caves and underground bunkers. The area was subjected to a heavy continuous bombardment by B-52 bombers.[120][121][122][123]

The U.S. forces and the Northern Alliance also began to diverge in their objectives. While the U.S. was continuing the search for Osama bin Laden, the Northern Alliance was pressuring for more support in their efforts to finish off the Taliban and control the country.

Battle of Mazar-i Sharif

The battle for Mazari Sharif was considered important, not only because it is the home of the Shrine of Hazrat Ali or "Blue Mosque", a sacred Muslim site, but also because it is the location of a significant transportation hub with two main airports and a major supply route leading into Uzbekistan.[124] It would also enable humanitarian aid to alleviate Afghanistan's looming food crisis, which had threatened more than six million people with starvation. Many of those in most urgent need lived in rural areas to the south and west of Mazar-i-Sharif.[124][125] On 9 November 2001, Northern Alliance forces, under the command of generals Abdul Rashid Dostum and Ustad Atta Mohammed Noor, swept across the Pul-i-Imam Bukhri bridge, meeting some resistance,[126][127] and seized the city's main military base and airport.

U.S. Special Operations Forces (namely Special Forces Operational Detachment A-595, CIA paramilitary officers and United States Air Force Combat Control Team[128][129][130] on horseback and using Close Air Support platforms, took part in the push into the city of Mazari Sharif in Balkh Province by the Northern Alliance. After a bloody 90-minute battle, Taliban forces, who had held the city since 1998, withdrew from the city, triggering jubilant celebrations among the townspeople whose ethnic and political affinities are with the Northern Alliance.[125][131]

The Taliban had spent three years fighting the Northern Alliance for Mazar-i-Sharif, precisely because its capture would confirm them as masters of all Afghanistan.[131] The fall of the city was a "body blow"[131] to the Taliban and ultimately proved to be a "major shock",[129] since the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) had originally believed that the city would remain in Taliban hands well into the following year,[132] and any potential battle would be "a very slow advance".[133]

Following rumors that Mullah Dadullah was headed to recapture the city with as many as 8,000 Taliban fighters, a thousand American 10th Mountain Division personnel were airlifted into the city, which provided the first solid foothold from which Kabul and Kandahar could be reached.[134][135] While prior military flights had to be launched from Uzbekistan or Aircraft carriers in theArabian Sea, now the Americans held their own airport in the country which allowed them to fly more frequent sorties for resupply missions and humanitarian aid. These missions allowed massive shipments of humanitarian aid to be immediately shipped to hundreds of thousands of Afghans facing starvation on the northern plain.[131][136]

The American-backed forces now controlling the city began immediately broadcasting from Radio Mazar-i-Sharif, the former Taliban Voice of Sharia channel on 1584 kHz,[137] including an address from former President Burhanuddin Rabbani.[138]

Fall of Kabul

On the night of 12 November, Taliban forces fled from the city of Kabul, leaving under the cover of darkness. By the time Northern Alliance forces arrived in the afternoon of 13 November, only bomb craters, burned foliage, and the burnt-out shells of Taliban gun emplacements and positions were there to greet them. A group of about twenty hardline fighters hiding in the city's park were the only remaining defenders. This Taliban group was killed in a 15-minute gun battle, being heavily outnumbered and having had little more than a telescope to shield them. After these forces were neutralized Kabul was in the hands of the U.S./NATO forces and the Northern Alliance.[139]

The fall of Kabul marked the beginning of a collapse of Taliban positions across the map. Within 24 hours, all the Afghan provinces along the Iranian border, including the key city of Herat, had fallen. Local Pashtun commanders and warlords had taken over throughout northeastern Afghanistan, including the key city of Jalalabad. Taliban holdouts in the north, mainly Pakistani volunteers, fell back to the northern city of Kunduz to make a stand. By 16 November, the Taliban's last stronghold in northern Afghanistan was besieged by the Northern Alliance. Nearly 10,000 Taliban fighters, led by foreign fighters, refused to surrender and continued to put up resistance. By then, the Taliban had been forced back to their heartland in southeastern Afghanistan around Kandahar.[140]

By 13 November, al-Qaeda and Taliban forces, with the possible inclusion of Osama bin Laden, had regrouped and were concentrating their forces in the Tora Bora cave complex, on the Pakistan border 50 kilometers (30 mi) southwest of Jalalabad, to prepare for a stand against the Northern Alliance and U.S./NATO forces. Nearly 2,000 al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters fortified themselves in positions within bunkers and caves, and by 16 November, U.S. bombers began bombing the mountain fortress. Around the same time, CIA and Special Forces operatives were already at work in the area, enlisting and paying local warlords to join the fight and planning an attack on the Tora Bora complex.[141]

Fall of Kunduz

Just as the bombardment at Tora Bora was stepped up, the siege of Kunduz that began on 16 November was continuing. Finally, after nine days of heavy fighting and American aerial bombardment, Taliban fighters surrendered to Northern Alliance forces on 25 November – 26 November. Shortly before the surrender, Pakistani aircraft arrived to evacuate intelligence and military personnel who had been in Afghanistan to aid the Taliban's ongoing fight against the Northern Alliance. However, during this airlift, it is alleged that up to five thousand people were evacuated from the region, including Taliban and al-Qaeda troops.[142][143][144]

Battle of Qala-i-Jangi

U.S. Army Special Forces with Hamid Karzai inKandahar province

By the end of November, Kandahar, the Taliban's birthplace, was its last remaining stronghold, and was coming under increasing pressure. Nearly 3,000 tribal fighters, led by Hamid Karzai, a loyalist of the former Afghan king, and Gul Agha Sherzai, the governor of Kandahar before the Taliban seized power, pressured Taliban forces from the east and cut off the northern Taliban supply lines to Kandahar. The threat of the Northern Alliance loomed in the north and northeast.

Meanwhile, nearly 1,000 U.S. Marines, ferried in by CH-53E Super Stallion helicopters and C-130s, set up a Forward Operating Base known as Camp Rhino in the desert south of Kandahar on 25 November. This was the coalition's first strategic foothold in Afghanistan, and was the stepping stone to establishing other operating bases. The first significant combat involving U.S. ground forces occurred a day after Rhino was captured when 15 armored vehicles approached the base and were attacked by helicopter gunships, destroying many of them. Meanwhile, the airstrikes continued to pound Taliban positions inside the city, where Mullah Omar was holed up. Omar, the Taliban leader, remained defiant although his movement only controlled 4 out of the 30 Afghan provinces by the end of November and called on his forces to fight to the death.

On 6 December, the U.S. government rejected any amnesty for Omar or any Taliban leaders. Shortly thereafter on 7 December, Omar slipped out of the city of Kandahar with a group of his hardcore loyalists and moved northwest into the mountains of Uruzgan Province, reneging on the Taliban's promise to surrender their fighters and their weapons. He was last reported seen driving off with a group of his fighters on a convoy of motorcycles.

Other members of the Taliban leadership fled into Pakistan through the remote passes of Paktia and Paktika Provinces. Nevertheless, Kandahar, the last Taliban-controlled city, had fallen, and the majority of the Taliban fighters had disbanded. The border town of Spin Boldak was surrendered on the same day, marking the end of Taliban control in Afghanistan. The Afghan tribal forces under Gul Agha seized the city of Kandahar while the U.S. Marines took control of the airport outside and established a U.S. base.

Battle of Tora Bora

The U.S. and its allies quickly drove the Taliban from power and captured all major cities and towns in the country. Many Al Qaeda and Taliban leaders escaped to neighboring Pakistan or retreated to rural or remote mountainous regions. In December 2001, the U.N. Security Councilestablished the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), to oversee security in the country and train the Afghan National Army. At the Bonn Conference in December 2001, Hamid Karzai was selected to head the Afghan Interim Administration, which after a loya jirga in Kabul in June 2002, became the Afghan Transitional Administration. In the popular elections of 2004, Karzai was elected the president of the new permanent Afghan government, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.[24]

In 2003, NATO assumed leadership of ISAF, included troops from 43 countries, with NATO members providing the core of the force.[25] Only a portion of U.S. forces in Afghanistan operate under NATO command; the rest remained under direct American command. Mullah Omar reorganized the Taliban movement and launched the insurgency against the Afghan government and ISAF forces in the spring of 2003.[26][27] Though vastly outgunned and outnumbered by NATO forces and the Afghan National Army, the Taliban and its allies, most notably the Haqqani Network and Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin, have waged asymmetric warfare with guerilla raids and ambushes in the countryside, suicide attacks against urban targets, and turncoat killings against coalition forces. The Taliban exploited the weak administration of the Afghan government, among the most corrupt in the world, to reassert influence across rural areas of southern and eastern Afghanistan. NATO countries responded in 2006 by increasing troops for operations to "clear and hold" villages and "nation building" projects to "win hearts and minds".[28][29]

While NATO forces continued to battle the Taliban insurgency, the war expanded into the tribal areas of neighboring North-West Pakistan.[30] In 2004, the Pakistani Army began to clash with local tribes hosting Al-Qaeda and Taliban forces. The U.S. military began to launch air strikes and then drone strikes into the region, targeting at first Al-Qaeda and later the local "Pakistan Taliban" leaders, which launched an insurgency in Waziristan in 2007.

On 2 May 2011, U.S. forces killed Osama bin Laden in Abbotabad, Pakistan. On 21 May 2012 the leaders of the NATO-member countries endorsed an exit strategy for removing NATO soldiers from Afghanistan.

Tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians have lost their lives in the war.[31]

Historical background

Origins of Afghanistan's civil warThe breakdown of Afghanistan's political order began with the overthrow of King Zahir Shah by his cousin Mohammed Daoud Khan in a bloodless coup in 1973. Daoud Khan, who had served as prime minister since 1953, continued to promote economic modernization, emanicipation of women and Pashtun nationalism, which was threatening to neighboring Pakistan, with its own restive Pashtun population. In the mid-1970s, Pakistani Prime MinisterZulfikar Ali Bhutto began to encourage Islamic leaders from Afghanistan such as Burhanuddin Rabbani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, to fight against the Daoud Khan regime. In 1978, Daoud Khan was killed in a coup by Afghan's Communist Party, his former partner in government, known as the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The PDPA pushed for socialist transformation of Afghan society by abolishing arranged marriages, promoting mass literacy and reforming land ownership, which undermined the traditional tribal order and provoked opposition from Islamic leaders across rural areas of the country. The PDPA's crackdown was met with open rebellion, including Ismail Khan's Herat Uprising. The PDPA itself was beset by leadership differences and weakened by another an internal coup on September 11, 1979 when Hafizullah Amin ousted Nur Muhammad Taraki. The Soviet Union, sensing PDPA weakness, intervened militarily three months later, to depose Amin and install another PDA faction led by Babrak Karmal.

Soviet troops in 1986

The entry of the Soviet Union into Afghanistan in December 1979 prompted its Cold War rivals, the United States, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Chinato support rebels fighting against the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan In contrast to the secular and socialist government, which controlled the cities, the religiously-motivated Mujahadeen held sway in large swathes of the countryside. Beside Rabbani, Hekmatar, Khan, other mujahedin commanders included Jalaluddin Haqqani, The CIA worked closely with Pakistan's Inter-Service Intelligence, the to funnel foreign support for the mujahedin to rebel groups across Afghanistan. The war also attracted Arab volunteers, known as "Afghan Arabs", including Osama Bin Laden.After the withdrawal of the Soviet military from Afghanistan in May 1989, the PDPA regime under Najibullah held on against the Mujahedeein until 1992 when the collapse of the Soviet Union deprived the regime of aid, and the defection of Uzbek general Abdul Rashid Dostum cleared the approach to Kabul. With the political stage cleared of Afghan socialists, the remaining Islamic warlords vied for power. By then Bin Laden had left the country. The United States' interest in Afghanistan also diminished.

Warlord Interregnum (1992-1996)

Main article: Civil war in Afghanistan (1992–96)

In 1992, Rabbani became president of the Islamic State of Afghanistan but this regime fought with other warlords for control of Kabul. In late 1994, Rabbani's defense minister, Ahmad Shah Massoud defeated Hekmatyr in Kabul and ended bombardments of the capital.[32][33][34] Massoud tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation. Other warlords maintained their fiefdoms such as Ismail Khan in the west and Dostum in the north.

In 1994, Mullah Omar, a Pashtun mujahedeen, who taught at a madrassa in Pakistan, returned to Kandahar and founded the Taliban. His followers were religious students, known as the Talib and they sought to end warlordism through strict adherence to Islamic law. By November 1994, the Taliban had captured all of Kandahar Province. They declined the government's offer to join in a coalition government and marched on Kabul in 1995.[35] The Taliban declined.[35]

Taliban Emirate vs Northern Alliance

The Taliban's early victories in 1994 were followed by a series of defeats that resulted in heavy losses.[36] Pakistan provided strong support to the Taliban.[37][38] Analysts such as Amin Saikal described the Taliban as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests, which the Taliban deny.[37] The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were driven by back by Massoud.[33][39]

On 27 September 1996, the Taliban, with military support by Pakistan and financial support by Saudi Arabia, seized Kabul and founded the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.[40] They imposed their fundamentalist interpretation of Islam in areas under their control, issuing edicts forbidding women to work outside the home, attend school, or to leave their homes unless accompanied by a male relative.[41] According to the Pakistani expert Ahmed Rashid, "between 1994 and 1999, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Pakistanis trained and fought in Afghanistan" on the side of the Taliban.[42][43]

Massoud and Dostum, former arch-enemies, created a United Front, commonly known as the Northern Alliance against the Taliban.[44] In addition to the Tajik forces of Massoud and the Uzbek forces of Dostum, the United Front included Hazara factions and Pashtun forces under the leadership of commanders such as Abdul Haq and Haji Abdul Qadir. Abdul Haq received a limited number of defecting Pashtun Taliban.[45] Both agreed to work together with the exiled Afghan king Zahir Shah.[43] International officials who met with representatives of the new alliance, which the journalistSteve Coll referred to as the "grand Pashtun-Tajik alliance", said, "It's crazy that you have this today ... Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Hazara ... They were all ready to buy in to the process ... to work under the king's banner for an ethnically balanced Afghanistan."[46][47] The Northern Alliance received varying degrees of support from Russia, Iran, Tajikistan and India.

The Taliban captured Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998 and drove Dostum went into exile.

The conflict was brutal. According the United Nations (UN), the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians.[48][49] UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001.[48][49] The Taliban especially targeted the Shiite Hazaras.[48][49] In retaliation of the execution of 3,000 Taliban prisoners by Uzbek general Abdul Malik Pahlawan in 1997, the Taliban executed about 4,000 civilians after taking Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998.[50][51]

Bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians.[52] The report by the United Nations quotes eyewitnesses in many villages describing "Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people".[48][49]

By 2001, the Taliban controlled as much as 90% of the country, with the Northern Alliance confined to northeast corner of Afghanistan. Fighting alongside Taliban forces were some 28,000-30,000 Pakistanis and 2,000-3,000 Al Qaeda militants.[35][52][53][54] Many of the Pakistanis were recruited from madrassas.[52] A 1998 document by the U.S. State Department confirmed that "20–40 percent of [regular] Taliban soldiers are Pakistani."[38] The document said that many of the parents of those Pakistani nationals "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan."[38] According to the U.S. State Department report and reports by Human Rights Watch, the other Pakistani nationals fighting in Afghanistan were regular soldiers, especially from the Frontier Corps, but also from the army providing direct combat support.[38][55]

Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan

In August 1996, Osama Bin Laden was forced to leave Sudan and arrived in Jalabad, Afghanistan. He had founded Al-Qaeda in the late 1980s to support the mujahdeen's war against the Soviets but became disillusioned by infighting among warlords. He grew close to Mullah Omar and moved Al Qaeda's operations to eastern Afghanistan.

The 9/11 Commission in the US reported found that under the Taliban, al-Qaeda was able to use Afghanistan as a place to train and indoctrinate fighters, import weapons, coordinate with other jihadists, and plot terrorist actions.[56] While al-Qaeda maintained its own camps in Afghanistan, it also supported training camps of other organizations. An estimated 10,000 and 20,000 men passed through these facilities before 9/11, most of whom were sent to fight for the Taliban against the United Front. A smaller number were inducted into al-Qaeda.[57]

After the August 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings were linked to bin Laden, President Bill Clinton ordered missile strikes on militant training camps in Afghanistan. U.S. officials pressed the Taliban to surrender bin Laden. In 1999, the international community imposed sanctions on the Taliban, calling for bin Laden to be surrendered. The Taliban repeatedly rebuffed their demands.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Special Activities Division paramilitary teams were active in Afghanistan in the 1990s in clandestine operations to locate and kill or capture Osama bin Laden. These teams planned several operations but did not receive the order to execute from President Clinton.[58] Their efforts built many of the relationships with Afghan leaders that proved essential in the 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan.[58]

Change in U.S. policy toward Afghanistan

During the Clinton administration, the U.S. tended to favor Pakistan and until 1998-1999 had no clear policy toward Afghanistan. In 1997, for instance, the U.S. State Department's Robin Raphel told Ahmad Shah Massoud to surrender to the Taliban. Massoud responded that, as long as he controlled an area the size of his hat, he would continue to defend it from the Taliban.[35] Around the same time, top foreign policy officials in the Clinton administration flew to northern Afghanistan to try to persuade the United Front not to take advantage of a chance to make crucial gains against the Taliban.[59][59] They insisted it was the time for a cease-fire and an arms embargo. At the time, Pakistan began a "Berlin-like airlift to resupply and re-equip the Taliban", financed with Saudi money.[59]

U.S. policy toward Afghanistan changed after the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings. Subsequently, Osama bin Laden was indicted for his involvement in the embassy bombings. In 1999 both the U.S. and the United Nations enacted sanctions against the Taliban via United Nations Security Council Resolution 1267, which demanded the Taliban surrender Osama bin Laden for trial in the U.S. and close all terrorist bases in Afghanistan.[60] The only collaboration between Massoud and the US at the time was an effort with the CIA to trace Osama bin Laden following the 1998 bombings.[61] The U.S. and the European Union provided no support to Massoud for the fight against the Taliban.

By 2001 the change of policy sought by CIA officers who knew Massoud was underway.[62] CIA lawyers, working with officers in the Near East Division and Counter-terrorist Center, began to draft a formal finding for President George W. Bush’s signature, authorizing a new covert action program in Afghanistan. It would be the first in a decade to seek to influence the course of the Afghan war in favor of Massoud.[46] Richard A. Clarke, chair of the Counter-Terrorism Security Group under the Clinton administration, and later an official in the Bush administration, allegedly presented a plan to incoming Bush administration official Condoleezza Rice in January 2001.

According to later reporting, a change in US policy was concluded in August 2001.[46] The Bush administration agreed on a plan to start giving support to the anti-Taliban forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud, who sought to create a democratic form of government in Afghanistan. A meeting of the Bush administration's top national security officials agreed that the Taliban would be presented in negotiations with a final ultimatum to hand over Osama bin Laden and other leading al-Qaeda operatives. If the Taliban refused, the US would provide covert military aid to anti-Taliban groups. If both those options failed, "the deputies agreed that the United States would seek to overthrow the Taliban regime through more direct action."[63]

Northern Alliance on the eve of 9/11

Ahmad Shah Massoud was the only leader of the United Front in Afghanistan. In the areas under his control, Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Declaration.[64] As a consequence, many civilians had fled during those years to areas under his control.[65][66] In total, estimates range up to one million people fleeing the Taliban.[67]

In late 2000, Massoud officially brought together this new alliance in a meeting in Northern Afghanistan to discuss "a Loya Jirga, or a traditional council of elders, to settle political turmoil in Afghanistan".[68] That part of the Pashtun-Tajik-Hazara-Uzbek peace plan did eventually develop. Among those in attendance was a Pashtun named Hamid Karzai.[69][70]

In early 2001, Massoud, with other ethnic leaders, addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, asking the international community to provide humanitarian help to the people of Afghanistan.(see video)[67] He said that the Taliban and al-Qaeda had introduced "a very wrong perception of Islam" and that without the support of Pakistan and Osama bin Laden, the Taliban would not be able to sustain their military campaign for up to a year.[67] On this visit to Europe, he warned that his intelligence had gathered information about a large-scale attack on U.S. soil being imminent.[71]

On 9 September 2001, Massoud was critically wounded in a suicide attack by two Arabs posing as journalists, who detonated a bomb hidden in their video camera during an interview in Khoja Bahauddin, in the Takhar Province of Afghanistan.[72][73] Massoud died in the helicopter taking him to a hospital. The funeral, held in a rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of mourning Afghans.

September 11, 2001 Attacks

On the morning of 11 September 2001, al-Qaeda carried out four coordinated attacks on U.S. soil. Four commercial passenger jet airliners were hijacked.[74][75] The hijackers intentionally crashed two of the airliners into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing everyone on board and thousands working in the buildings. Both buildings collapsed within two hours from fire damage related to the crashes, destroying nearby buildings and damaging others. The hijackers crashed a third airliner into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, just outsideWashington, D.C.. The fourth plane crashed into a field near Shanksville, in rural Pennsylvania, after some of its passengers and flight crew attempted to retake control of the plane, which the hijackers had redirected toward Washington, D.C to target the White House, or the U.S. Capitol. No flights had survivors.

Nearly 3,000 people, including the 19 hijackers, died in the attacks.[76] According to the New York State Health Department, 836 responders, including firefighters and police personnel, have died as of June 2009.[76]

On 11 September, the Taliban's foreign minister, Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil, "denounce[d] the terrorist attack, whoever is behind it."[77] The following day, President Bush called the attacks more than just "acts of terror" but "acts of war" and resolved to pursue and conquer an "enemy" that would no longer be safe in "its harbors."[78] The Taliban ambassador to Pakistan, Abdul Salam Zaeef said on 13 September that the Taliban would consider extraditing bin Laden if there was solid evidence linking him to the attacks.[79] Though in 2004, Osama bin Laden eventually took responsibility for the 9/11 attacks, he denied having any involvement in a statement issued on September 17 and by interview on September 29.[80][81]

The State Department, in a memo dated 14 September, demanded that the Taliban surrender all known al-Qaeda associates in Afghanistan, provide intelligence on him and his affiliates, and expel all terrorists from Afghanistan.[83] On 18 September, the director of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence, Mahmud Ahmedconveyed these demands to Mullah Omar and the senior Taliban leadership, whose response was "not negative on all points."[84] Mahmoud reported that the Taliban leadership was in "deep introspection" and waiting for the recommendation of a grand council of religious clerics that was assembling to decide the matter.[84] On 20 September, President Bush, in an address to Congress, demanded the Taliban deliver Osama bin Laden and destroy bases of al Qaeda.[85]

In the days and weeks immediately following 9/11, when the Taliban sought evidence of his involvement in the attacks, Osama bin Laden repeatedly denied having any role.

The same day, a grand council of over 1,000 Muslim clerics from across Afghanstan, which had convened at the request of the Taliban leadership to decide the fate of bin Laden, issued a fatwa, expressing sadness for the deaths in the 9/11 attacks, urging bin Laden to leave their country, and calling on theUnited Nations and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to conduct an independent investigation of "recent events to clarify the reality and prevent harassment of innocent people."[86] The fatwa went on to warn that should the United States not agree with its decision and invade Afghanistan, "jihad becomes an order for all Muslims."[86] White House spokesperson Ari Fleischer rejected the response, saying the time for talk had ended and it was time for action.[87]

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell toldMeet the Press on 23 September 2001, that the U.S. government would release evidence linking Osama bin Laden to the 9/11 attacks. The evidence, however, was not made public prior to the outbreak of war.

On 21 September, Taliban representatives in Pakistan reacted to the U.S. response with defiance.[88] Zaeef said the Taliban were ready, if necessary, for war with the United States.[88] His deputy Suhail Shaheen, warned that a U.S. invasion would share in the same fate that befell Great Britain and the Soviet Union in previous centuries.[88] Zaeef reiterated the demand for evidence of bin Laden's involvement in the 9/11 attacks.[88] "If the Americans provide evidence, we will cooperate with them, but they do not provide evidence," he said.[88] "In America, if I think you are a terrorist, is it properly justified that you should be punished without evidence?" he asked.[88] "This is an international principle. If you use the principle, why do you not apply it to Afghanistan?"[88] On 23 September, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell told NBC's Meet the Press that the U.S. government would, "in the near future" release "a document that will describe quite clearly the evidence . . . linking [bin Laden] to this attack."[89] The evidence was not made public but instead shown to Pakistan's government whose leaders later stated that the materials they had seen "provide[d] sufficient basis for indictment in a court of law."[90] Pakistan ISI chief Lieutenant General Mahmud Ahmed shared information provided to him by the U.S. with Taliban leaders.[91]

On 24 September, ISI Director Mahmoud told U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan that while the Taliban was "weak and ill-prepared to face the American onslaught", "real victory will come through negotiations" for if the Taliban were eliminated, Afghanistan would revert to warlordism.[92] On 28 September, he led a delegation of eight Pakistani religious leaders to persuade Mullah Omar to accept having religious leaders from Islamic countries examine the evidence and decide bin Laden's fate.[93] Mullah Omar was noncommittal.[93] The U.S. government remained opposed to any negotiations with the Taliban.[93]

Meanwhile the U.S. Department of Defense under Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, was exploring ways to broaden the military response beyond Afghanistan.[94] In a memo to President Bush on September 30, Rumsfeld argued "finding a few hundred terrorists in the caves of Afghanistan," was not the U.S. government's "strong suit" which should instead use "the vastness of our military and humanitarian resources," to strengthen the domestic opposition in "terrorist-supporting states" and achieve regime change in "Afghanistan and another key State (or two) that supports terrorism."[94]

On 30 September 2001, the U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeldurged a broader military response to the 9/11 attacks, going beyondregime change in Afghanistan to "another key State (or two) that support terrorism."

On 1 October, Mullah Omar agreed to a proposal by Qazi Hussain Ahmad, the head of Pakistan's most important Islamic party, the Jamaat-i-Islami, to have bin Laden taken to Pakistan where he would be held under house arrest in Peshawarand tried by an international tribunal.[95] But Pakistan's president Pervez Musharraf blocked the plan because he could not guarantee bin Laden's safety.[95] On 2 October, Zaeef appealed the United States to negotiate, "We do not want to compound the problems of the people, the country or the region."[96] He pleaded, "the Afghan people need food, need aid, need shelter, not war."[96] The U.S. government refused to negotiate and instead focused on building a new government around former Afghan King Zahir Shah.[96] The British Prime Minister Tony Blair called on the Taliban to "surrender the terrorists or surrender power."[97] Mullah Omar warned that unlike the former King's government which was overthrown in 1973 and surrendered, the Taliban "would just retreat to the mountains" and continue to fight.[96]

On 5 October, the Taliban offered to try bin Laden in an Afghan court, so long as the U.S. provided what it called "solid evidence" of his guilt.[98] The U.S. government dismissed the request for proof as "request for delay or prevarication"; NATO commander George Robertson said the evidence was "clear and compelling."[97] On 7 October, as the U.S. aerial bombing campaign began, President Bush ignored questions about the Taliban's offer and said instead "Full warning had been given, and time is running out."[99] The same day, the State Department gave the Pakistani government one last message to the Taliban: Hand over all al-Qaeda leaders or "every pillar of the Taliban regime will be destroyed."[100]

A week into the bombing campaign, on 14 October, Abdul Kabir, the Taliban's third ranking leader, offered to hand over bin Laden if the U.S. government provided evidence of his guilt and halted the bombing campaign. President Bush rejected the offer as non-negotiable.[101]On 16 October, Muttawakil, the Taliban foreign minister, dropped the condition to see evidence and offered to send bin Laden to a third country in return for a halt to the bombing.[102] US officials also rejected this offer.[103] At that time, some Afghan experts said the United States failed to recognize the Taliban's need for a "face saving formula."[104] In 2007, bin Laden indicated that the Taliban had no knowledge of his plans for the 9/11 attacks.[105]

Legal basis for war

On 14 September 2001, Congress passed legislation titled Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, which was signed on 18 September 2001 by President Bush. It authorized the use of U.S. Armed Forces against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks. The Bush administration, for its part, did not seek a declaration of war by Congress, and labeled Taliban troops as supporters of terrorists rather than soldiers. It thus defined them as outside the protections of the Geneva Convention and due process of law. This position was later overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2008, following other decisions that overturned some Bush executive positions in the war on terror.[106] Military lawyers responsible for prosecuting detainees also had questioned some of the policies, and such internal disagreements were revealed years later in the press.[107]

The United Nations Charter, to which all the Coalition countries are signatories, provides that all UN member states must settle their international disputes peacefully and no member nation can use military force except in self-defense. The U.S. Constitution states that international treaties, such as the United Nations Charter, that are ratified by the U.S. are part of the law of the land, though subject to effective repeal by any subsequent act of the U.S. Congress (i.e., the "leges posteriores priores contrarias abrogant" or "last in time" canon of statutory interpretation).[108] The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) did not authorize the U.S.-led military campaign in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom).

Defenders of the legitimacy of the U.S.-led invasion argue that U.N. Security Council authorization was not required since the invasion was an act of collective self-defense provided for under Article 51 of the UN Charter, and not a war of aggression.[108][109] Critics maintain that the bombing and invasion of Afghanistan were not legitimate self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter because the 9/11 attacks were not “armed attacks” by another state, but were perpetrated by non-state actors. They said these attackers had no proven connection to Afghanistan or the Taliban rulers. Such critics have said that, even if a state had made the 9/11 attacks, no bombing campaign would constitute self-defense. They interpreted self-defense to be actions that were "instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation."[108]

On 20 December 2001, more than two months after the U.S.-led attack began, the UNSC authorized the creation of an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to take all measures necessary to fulfill its mandate of assisting the Afghan Interim Authority in maintaining security.[110] Command of the ISAF passed to NATO on 11 August 2003, following the US invasion of Iraq in March of that year.[111]

History of the conflict

On 7 October 2001, the U.S. government launched military operations in Afghanistan. On 7 October 2001, airstrikes were reported in Kabul (where electricity supplies were severed), at the airport, at Kandahar (home of the Taliban's Supreme Leader Mullah Omar), and in the city of Jalalabad. CNN released exclusive footage of Kabul being bombed to American broadcasters at approximately 5:08 pm 7 October 2001.[112]

On the ground, teams from the CIA's Special Activities Division (SAD) were the first U.S. forces to enter Afghanistan and begin combat operations. They were soon joined by U.S. Army Special Forces from the 5th Special Forces Group and other units fromUSSOCOM.[113][114]At 17:00 UTC, President Bush confirmed the strikes on national television and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Tony Blair also addressed the UK. Bush stated that Taliban military sites and terrorist training grounds would be targeted. In addition, food, medicine, and supplies would be dropped to "the starving and suffering men, women and children of Afghanistan".[116]

Bin Laden released a prerecorded videotape before the attacks in which he condemned any attacks against Afghanistan. Al Jazeera, the Arabic satellite news channel, reported that the tapes were received shortly before the attack.

British and American special forces worked jointly to take Herat in November 2001. These forces worked with Afghan opposition groups on the ground, in particular the Northern Alliance. The United Kingdom, Canada and Australia also deployed forces, and several other countries provided basing, access and overflight permission.

The U.S. was able to track Mohammed Atef, al-Qaeda's number three at the time, who was one of the most wanted. He was killed by bombing at his Kabul home between 14–16 November 2001, along with his guard Abu Ali al-Yafi'i and six others.[117][118] This was one of America's first and largest victories during the early stages of the war.

Air campaigns

| “ | Having begun the war with the greatest imaginable reservoir of moral authority, the U.S. was on the verge of letting it slip away through high-level attacks using the most ghastly inventions its scientists could come up with. | ” |

| —Stephen Tanner, Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the War against the Taliban[119] | ||

The strikes initially focused on the area in and around the cities of Kabul, Jalalabad, and Kandahar. Within a few days, most Taliban training sites were severely damaged, and the Taliban's air defenses were destroyed. The campaign focused on command, control, and communication targets, which weakened the ability of the Taliban forces to communicate. But, the line facing the Afghan Northern Alliance held, and no battlefield successes were achieved. Two weeks into the campaign, the Northern Alliance demanded the air campaign focus more on the front lines.

The next stage of the campaign began with carrier based F/A-18 Hornet fighter-bombers hitting Taliban vehicles in pinpoint strikes, while other U.S. planes began cluster bombing Taliban defenses. For the first time in years, Northern Alliance commanders began to see the substantive results that they had long hoped for on the front lines.

At the beginning of November, the allied forces attacked front lines with daisy cutter bombs, and by AC-130 gunships. The Taliban fighters had no previous experience with American firepower, and often stood on top of bare ridgelines where U.S. Army Special Forces could easily spot them and call in close air support. By 2 November, Taliban frontal positions were devastated, and a Northern Alliance march on Kabul seemed possible. According to author Stephen Tanner,

"After a month of the U.S. bombing campaign rumblings began to reach Washington from Europe, the Mideast, and Pakistan where Musharraf had requested the bombing to cease. Having begun the war with the greatest imaginable reservoir of moral authority, the U.S. was on the verge of letting it slip away through high-level attacks using the most ghastly inventions its scientists could come up with."[119]

President George W. Bush went to New York City on 10 November 2001, "where the wreckage of the World Trade Center still smoldered with underground fires",[119]to address the United Nations. He said that not only the U.S. was in danger of further attacks by the 9/11 terrorists, but so was every other countries in the world. Tanner writes: "His words had impact. Most of the world renewed its support for the American effort, including commitments of material help from Germany, France, Italy, Japan and other countries."[119]

Fighters from al-Qaeda took over security in the Afghan cities, demonstrating the instability of the Taliban regime. The Northern Alliance and their Central Intelligence Agency/Special Forces advisers planned the next stage of their offensive. Northern Alliance troops would seize Mazari Sharif, thereby cutting off Taliban supply lines and enabling the flow of equipment from the countries to the north, followed by an attack on Kabul itself.

Areas most targeted

During the early months of the war, the U.S. military had a limited presence on the ground. The plan was that Special Forces, and intelligence officers with a military background, would serve as liaisons with Afghan militias opposed to the Taliban, would advance after the cohesiveness of the Taliban forces was disrupted by American air power.[120][121][122]

The Tora Bora Mountains lie roughly east of Afghanistan's capital Kabul, which is close to the border with Pakistan. American intelligence analysts believed that the Taliban and al-Qaeda had dug in behind fortified networks of well-supplied caves and underground bunkers. The area was subjected to a heavy continuous bombardment by B-52 bombers.[120][121][122][123]

The U.S. forces and the Northern Alliance also began to diverge in their objectives. While the U.S. was continuing the search for Osama bin Laden, the Northern Alliance was pressuring for more support in their efforts to finish off the Taliban and control the country.

Battle of Mazar-i Sharif

The battle for Mazari Sharif was considered important, not only because it is the home of the Shrine of Hazrat Ali or "Blue Mosque", a sacred Muslim site, but also because it is the location of a significant transportation hub with two main airports and a major supply route leading into Uzbekistan.[124] It would also enable humanitarian aid to alleviate Afghanistan's looming food crisis, which had threatened more than six million people with starvation. Many of those in most urgent need lived in rural areas to the south and west of Mazar-i-Sharif.[124][125] On 9 November 2001, Northern Alliance forces, under the command of generals Abdul Rashid Dostum and Ustad Atta Mohammed Noor, swept across the Pul-i-Imam Bukhri bridge, meeting some resistance,[126][127] and seized the city's main military base and airport.