Doomed: The Rise & Fall of Deadwood's Chinatown

USINFO | 2013-05-27 09:47

More than half of the lots sit vacant along a lonely two-block stretch of Black Hills road. A layer of crushed rock covers most of the empty land, making life difficult for the few dandelion tenants that take root in the spring. A century ago this was a thriving community with its own court of justice, religious buildings, police force and fire department. Now the once-bustling burg is all but abandoned, with only three buildings left standing – none of which date from its turn-of-the-century heyday.

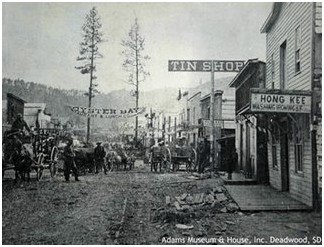

But this ghost town isn’t located at the bottom of some forsaken valley, nor is it lost at the top of a mountain peak where the gold mines ran dry long ago. Once known as Chinatown, this forgotten city sits in the very center of Deadwood, where upwards of two million visitors unknowingly stroll through it each year.

At its peak, the boundaries of Deadwood’s Chinatown stretched from the present intersection of Main Street and U.S. 85 to the location of the modern Mineral Palace Hotel. Grocers, boarding houses, bakeries, opium dens, gambling halls and stables lined the street in between, which bustled with the noise of several hundred residents. The ubiquitous Chinese laundry was there too, and several more were conveniently scattered throughout the city. Leading businessmen organized rival hose teams, a type of volunteer fire department that also doubled as an athletic team in celebratory foot races. A joss house served as both a temple and a court of law. Emporiums sold foods, spices and medicines imported from China – true luxuries, given the 7,300-mile journey by ship, rail and wagon. The more Deadwood prospered, the more Chinatown grew.

But Deadwood’s prosperity couldn’t compete with national sentiment. A flurry of anti-immigration laws kept the town’s largely bachelor Chinese population from replenishing itself. At the same time, the ethnic enclaves or larger urban centers on America’s coasts grew in size, enticing the Chinese living in the Black Hills with the promise of new economic opportunities. Deadwood’s Chinatown shrunk significantly following the birth of the 20th century, and by 1940 there were only two known persons of Chinese origin in the entirety of Lawrence County.

Though visibly faded, the community has never been entirely erased from Deadwood. Fueled by a mix of history and local legend, the rise and fall of Chinatown still exudes an influence over the city today, beckoning to residents and visitors alike with its historically exotic allure.

GOLD MOUNTAIN

While the Chinese immigrants who flooded into the United States during the latter half of the 19th century came from a culture utterly foreign to the American Frontier, they had the same reasons for migrating as most white pioneers: gold. The bloody Taiping Rebellion, which claimed upwards of 20 million lives between 1851 and 1864, sandwiched by the Opium Wars with Britain, created miserable living conditions for many in China. News of California’s 1849 gold rush infused hope into the hearts of the common people, who began referring to America as gam saan (金山), or gold mountain.

Filled with visions of wealth and an easier life, tens of thousands began making the perilous four-month journey across the ocean on clipper ships and older sailing vessels. The $200 to $300 price of passage was steeper than many Chinese could afford, and occasionally up to 20% of the passengers would die en route. The dangers did little to discourage waves of Chinese immigrants, who engaged in prospecting, laboring and general commerce.

But as the placer deposits petered out on America’s West Coast, prospectors moved inland toward other gold discoveries. The 1876 rush to the Black Hills, the last of the nation’s major gold rushes, attracted thousands of eager miners, including many of Chinese origin. Coupled with a national financial crisis caused by the Panic of 1873, the rich placer claims of Deadwood seem to offer the perfect financial opportunity.

“You have a recession going on, and the announcement that gold has been discovered, and the Chinese, like everyone else, were very eager to capitalize on that announcement,” explains Mary Kopco, director of the Adams Museum and House in Deadwood. “Many came to set up businesses to service the mining camp, and others came to work the placers.”

However, census figures indicate that only a small portion of Deadwood’s Chinese were engaged in mining. Most chose to operate restaurants, boarding houses, the ubiquitous laundry and other service-related businesses, perhaps in an effort to avoid the unpleasant confrontations with jealous white prospectors that marked many other Western gold camps.

“They did the placer mining as much as the local miners would allow them,” says Eileen French, an amateur local historian. “There was resistance, just like we have resistance to immigration today. People feel threatened.”

“Where you see the hatred and animosity is where the Chinese come and work the mines,” echoes David Wolff, an associate professor of history at Black Hills State University. “Now some of the Chinese did work claims on lower Whitewood Creek. But the sense is that everyone thought, ‘Well, they’re so far down there, that’s the worst mining ground anyway.’ And it was pretty bad for mining, but some of them did pretty well.”

The success of Chinese miners was significant enough to make the newspapers of the day, which reported on October 4, 1878 that one fortunate immigrant had discovered “a nugget on his claim that weighed over four hundred dollars.” A few months later the Black Hills Daily Times wrote that a certain group of Chinese using sluices “have been taking out at the rate of $4 to the heathen, while the white miners were unable to make the water run.”

Liping Zhu, associate professor of history at Eastern Washington University, points to several reasons for the achievements of Chinese prospectors. “A spirit of teamwork, water management skills, nutritious diets, advanced healthcare and environmental adaptation abilities all contributed to the success,” he wrote in Ethnic Oasis: The Chinese in the Black Hills.

Laundries were one of the more popular business choices for the Chinese in Deadwood, due to their low start-up costs (less than $20, according to Zhu), low overhead (water from the creek and wood from the forest were free) and high profit potential. Zhu notes that most miners were taking in between $4 and $7 per day in the late 1870s, while a savvy laundry operator could make $10 or better.

In fact, the Chinese held a virtual monopoly on laundry business in Deadwood for several decades – a business advantage they protected with a vengeance. After years of complaining about the high prices of laundry services, Deadwood residents rejoiced in 1880 when two white women built their own laundry establishment in town. The Chinese laundries responded by severely underselling their new competition, who soon went out of business – at which point the Chinese brought their rates back up to previous levels.

But this ghost town isn’t located at the bottom of some forsaken valley, nor is it lost at the top of a mountain peak where the gold mines ran dry long ago. Once known as Chinatown, this forgotten city sits in the very center of Deadwood, where upwards of two million visitors unknowingly stroll through it each year.

At its peak, the boundaries of Deadwood’s Chinatown stretched from the present intersection of Main Street and U.S. 85 to the location of the modern Mineral Palace Hotel. Grocers, boarding houses, bakeries, opium dens, gambling halls and stables lined the street in between, which bustled with the noise of several hundred residents. The ubiquitous Chinese laundry was there too, and several more were conveniently scattered throughout the city. Leading businessmen organized rival hose teams, a type of volunteer fire department that also doubled as an athletic team in celebratory foot races. A joss house served as both a temple and a court of law. Emporiums sold foods, spices and medicines imported from China – true luxuries, given the 7,300-mile journey by ship, rail and wagon. The more Deadwood prospered, the more Chinatown grew.

But Deadwood’s prosperity couldn’t compete with national sentiment. A flurry of anti-immigration laws kept the town’s largely bachelor Chinese population from replenishing itself. At the same time, the ethnic enclaves or larger urban centers on America’s coasts grew in size, enticing the Chinese living in the Black Hills with the promise of new economic opportunities. Deadwood’s Chinatown shrunk significantly following the birth of the 20th century, and by 1940 there were only two known persons of Chinese origin in the entirety of Lawrence County.

Though visibly faded, the community has never been entirely erased from Deadwood. Fueled by a mix of history and local legend, the rise and fall of Chinatown still exudes an influence over the city today, beckoning to residents and visitors alike with its historically exotic allure.

GOLD MOUNTAIN

While the Chinese immigrants who flooded into the United States during the latter half of the 19th century came from a culture utterly foreign to the American Frontier, they had the same reasons for migrating as most white pioneers: gold. The bloody Taiping Rebellion, which claimed upwards of 20 million lives between 1851 and 1864, sandwiched by the Opium Wars with Britain, created miserable living conditions for many in China. News of California’s 1849 gold rush infused hope into the hearts of the common people, who began referring to America as gam saan (金山), or gold mountain.

Filled with visions of wealth and an easier life, tens of thousands began making the perilous four-month journey across the ocean on clipper ships and older sailing vessels. The $200 to $300 price of passage was steeper than many Chinese could afford, and occasionally up to 20% of the passengers would die en route. The dangers did little to discourage waves of Chinese immigrants, who engaged in prospecting, laboring and general commerce.

But as the placer deposits petered out on America’s West Coast, prospectors moved inland toward other gold discoveries. The 1876 rush to the Black Hills, the last of the nation’s major gold rushes, attracted thousands of eager miners, including many of Chinese origin. Coupled with a national financial crisis caused by the Panic of 1873, the rich placer claims of Deadwood seem to offer the perfect financial opportunity.

“You have a recession going on, and the announcement that gold has been discovered, and the Chinese, like everyone else, were very eager to capitalize on that announcement,” explains Mary Kopco, director of the Adams Museum and House in Deadwood. “Many came to set up businesses to service the mining camp, and others came to work the placers.”

However, census figures indicate that only a small portion of Deadwood’s Chinese were engaged in mining. Most chose to operate restaurants, boarding houses, the ubiquitous laundry and other service-related businesses, perhaps in an effort to avoid the unpleasant confrontations with jealous white prospectors that marked many other Western gold camps.

“They did the placer mining as much as the local miners would allow them,” says Eileen French, an amateur local historian. “There was resistance, just like we have resistance to immigration today. People feel threatened.”

“Where you see the hatred and animosity is where the Chinese come and work the mines,” echoes David Wolff, an associate professor of history at Black Hills State University. “Now some of the Chinese did work claims on lower Whitewood Creek. But the sense is that everyone thought, ‘Well, they’re so far down there, that’s the worst mining ground anyway.’ And it was pretty bad for mining, but some of them did pretty well.”

The success of Chinese miners was significant enough to make the newspapers of the day, which reported on October 4, 1878 that one fortunate immigrant had discovered “a nugget on his claim that weighed over four hundred dollars.” A few months later the Black Hills Daily Times wrote that a certain group of Chinese using sluices “have been taking out at the rate of $4 to the heathen, while the white miners were unable to make the water run.”

Liping Zhu, associate professor of history at Eastern Washington University, points to several reasons for the achievements of Chinese prospectors. “A spirit of teamwork, water management skills, nutritious diets, advanced healthcare and environmental adaptation abilities all contributed to the success,” he wrote in Ethnic Oasis: The Chinese in the Black Hills.

Laundries were one of the more popular business choices for the Chinese in Deadwood, due to their low start-up costs (less than $20, according to Zhu), low overhead (water from the creek and wood from the forest were free) and high profit potential. Zhu notes that most miners were taking in between $4 and $7 per day in the late 1870s, while a savvy laundry operator could make $10 or better.

In fact, the Chinese held a virtual monopoly on laundry business in Deadwood for several decades – a business advantage they protected with a vengeance. After years of complaining about the high prices of laundry services, Deadwood residents rejoiced in 1880 when two white women built their own laundry establishment in town. The Chinese laundries responded by severely underselling their new competition, who soon went out of business – at which point the Chinese brought their rates back up to previous levels.

Share this page