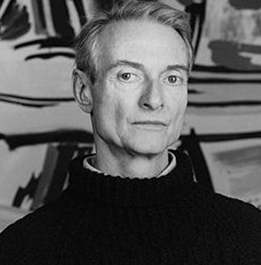

Roy Lichtenstein (pronounced ˈlɪktənˌstaɪn; October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997) was an American pop artist. During the 1960s, his paintings were exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City and, along with Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, and others. He became a leading figure in the new art movement. His work defined the basic premise of pop art better than any other through parody.[2] Favoring the old-fashioned comic strip as subject matter, Lichtenstein produced hard-edged, precise compositions that documented while it parodied often in a tongue-in-cheek humorous manner. His work was heavily influenced by both popular advertising and the comic book style. He described pop art as, not 'American' painting but actually industrial painting.[3]

Roy Lichtenstein was born in New York City, into an upper-middle-class Jewish[1] family. His father, Milton, was a real estate broker, his mother, Beatrice (Werner), a homemaker.[4] He was raised on the Upper West Side and attended public school until the age of twelve.

He then enrolled at New York's Franklin School for Boys, remaining there for his secondary education. Lichtenstein first became interested in art and design as a hobby, and through school.[5] He was an avid jazz fan, often attending concerts at the Apollo Theater in Harlem.[5] He frequently drew portraits of the musicians playing their instruments.[5] In his last year of high school, 1939, Lichtenstein enrolled in summer classes at the Art Students League of New York, where he worked under the tutelage of Reginald Marsh.[6]

Career

Cap de Barcelona, sculpture, mixed media, Barcelona (reverse side)

Lichtenstein then left New York to study at the Ohio State University, which offered studio courses and a degree in fine arts.[1] His studies were interrupted by a three-year stint in the army during and after World War II between 1943 and 1946.[1] After being in training programs for languages, engineering, and pilot training, all of which were cancelled, he served as an orderly, draftsman, and artist.[1]

Lichtenstein returned home to visit his dying father and was discharged from the army with eligibility for the G.I. Bill.[5] He returned to studies in Ohio under the supervision of one of his teachers, Hoyt L. Sherman, who is widely regarded to have had a significant impact on his future work (Lichtenstein would later name a new studio he funded at OSU as the Hoyt L. Sherman Studio Art Center).[7]

Lichtenstein entered the graduate program at Ohio State and was hired as an art instructor, a post he held on and off for the next ten years. In 1949 Lichtenstein received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Ohio State University.

In 1951 Lichtenstein had his first solo exhibition at the Carlebach Gallery in New York.[1][8] He moved to Cleveland in the same year, where he remained for six years, although he frequently traveled back to New York. During this time he undertook jobs as varied as a draftsman to a window decorator in between periods of painting.[1] His work at this time fluctuated between Cubism and Expressionism.[5] In 1954, his first son, David Hoyt Lichtenstein, now a songwriter, was born. His second son, Mitchell Lichtenstein, was born in 1956.

In 1957, he moved back to upstate New York and began teaching again.[3] It was at this time that he adopted the Abstract Expressionism style, being a late convert to this style of painting.[10] Lichtenstein began teaching in upstate New York at the State University of New York at Oswego in 1958.

Rise to fame

In 1960, he started teaching at Rutgers University where he was heavily influenced by Allan Kaprow, who was also a teacher at the university. This environment helped reignite his interest in Proto-pop imagery.[1] In 1961, Lichtenstein began his first pop paintings using cartoon images and techniques derived from the appearance of commercial printing. This phase would continue to 1965, and included the use of advertising imagery suggesting consumerism and homemaking.[5] His first work to feature the large-scale use of hard-edged figures and Ben-Day dots was Look Mickey (1961, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.).[11] This piece came from a challenge from one of his sons, who pointed to a Mickey Mouse comic book and said; I bet you can't paint as good as that, eh, Dad[12] In the same year he produced six other works with recognizable characters from gum wrappers and cartoons.[13]

In 1961, Leo Castelli started displaying Lichtenstein's work at his gallery in New York. Lichtenstein had his first one-man show at the Castelli gallery in 1962; the entire collection was bought by influential collectors before the show even opened.[1] A group of paintings produced between 1961-1962 focused on solitary household objects such as sneakers, hot dogs, and golf balls.[14] In September 1963 he took a leave of absence from his teaching position at Douglass College at Rutgers.

Fame

Drowning Girl (1963).On display at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

It was at this time, that Lichtenstein began to find fame not just in America but worldwide. He moved back to New York to be at the center of the art scene and resigned from Rutgers University in 1964 to concentrate on his painting.[16] Lichtenstein used oil and Magna paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Girl (1963), which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics' Secret Hearts #83.

(Drowning Girl now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, New York.[17]) Drowning Girl also features thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots, as if created by photographic reproduction. Of his own work Lichtenstein would say that Abstract Expressionists put things down on the canvas and responded to what they had done, to the color positions and sizes. My style looks completely different, but the nature of putting down lines pretty much is the same; mine just don't come out looking calligraphic, like Pollock's or Kline's.[18]

Rather than attempt to reproduce his subjects, his work tackled the way mass media portrays them. Lichtenstein would never take himself too seriously however I think my work is different from comic strips- but I wouldn't call it transformation; I don't think that whatever is meant by it is important to art.[19] When his work was first released, many art critics of the time challenged its originality. His work was harshly criticized as vulgar and empty. The title of a Life magazine article in 1964 asked, “Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.”[20]

Lichtenstein responded to such claims by offering responses such as the following The closer my work is to the original, the more threatening and critical the content. However, my work is entirely transformed in that my purpose and perception are entirely different. I think my paintings are critically transformed, but it would be difficult to prove it by any rational line of argument.[21] He discussed experiencing this heavy criticism in interview with April Bernard and Mimi Thompson in 1986. Suggesting that it was at times difficult to be criticized, Lichtenstein said, “I don’t doubt when I’m actually painting, it’s the criticism that makes you wonder, it does.”[22]

Whaam!, 1963, Tate Modern

His most famous image is arguably Whaam! (1963, Tate Modern, London[23]), one of the earliest known examples of pop art, adapted a comic-book panel from a 1962 issue of DC Comics' All-American Men of War.[24] The painting depicts a fighter aircraft firing a rocket into an enemy plane, with a red-and-yellow explosion. The cartoon style is heightened by the use of the onomatopoeic lettering Whaam! and the boxed caption I pressed the fire control... and ahead of me rockets blazed through the sky... This diptych is large in scale, measuring 1.7 x 4.0 m (5 ft 7 in x 13 ft 4 in).[23] Whaam is widely regarded as one of his finest and most notable works. It follows the comic strip-based themes of some of his previous paintings and is part of a body of war-themed work created between 1962 and 1964. It is one of his two notable large war-themed paintings. It was purchased by the Tate Modern in 1966, after being exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1963, and has remained in their collection since.

Lichtenstein began experimenting with sculpture around 1964, demonstrating a knack for the form that was at odds with the insistent flatness of his paintings. For Head of Girl (1964), and Head with Red Shadow (1965), he collaborated with a ceramicist who sculpted the form of the head out of clay. Lichtenstein then applied a glaze to create the same sort of graphic motifs that he used in his paintings; the application of black lines and Ben-day dots to three-dimensional objects resulted in a flattening of the form[25]

Most of his best-known artworks are relatively close, but not exact, copies of comic book panels, a subject he largely abandoned in 1965.

(He would occasionally incorporate comics into his work in different ways in later decades.) These panels were originally drawn by such comics artists as Jack Kirby and DC Comics artists Russ Heath, Tony Abruzzo, Irv Novick, and Jerry Grandenetti, who rarely received any credit. Jack Cowart, executive director of the Lichtenstein Foundation, contests the notion that Lichtenstein was a copyist, saying Roy's work was a wonderment of the graphic formulae and the codification of sentiment that had been worked out by others. The panels were changed in scale, color, treatment, and in their implications. There is no exact copy.[26] However, some[27] have been critical of Lichtenstein's use of comic-book imagery and art pieces, especially insofar as that use has been seen as endorsement of a patronizing view of comics by the art mainstream;[27] noted comics author Art Spiegelman commented that Lichtenstein did no more or less for comics than Andy Warhol did for soup.[27]

In 1966, Lichtenstein moved on from his much-celebrated imagery of the early 1960s, and began his Modern Paintings series, including over 60 paintings and accompanying drawings. Using his characteristic Ben Day dots and geometric shapes and lines, he rendered incongruous, challenging images out of familiar architectural structures, patterns borrowed from Art Déco and other subtly evocative, often sequential, motifs.[28] The Modern Sculpture series of 1967–8 made reference to motifs from Art Déco architecture.[29]