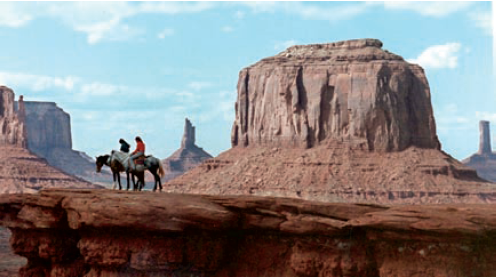

Monument Valley is often featured in American movies, especially the classic westerns of director John Ford.

The American film industry, despite its critics, continues to dominate the world market for movies. The author discusses why this is and relates the impact of several recent movies in the United States and abroad. Thomas Doherty is a professor of film studies at Brandeis University near Boston, Massachusetts, and the author of several books, including Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II (1999) and Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s (2002).

The Americans have colonized our subconscious,” says a character in Wim Wenders’s Kings of the Road (1976), speaking as much in admiration as complaint, which only makes sense in a road movie by a German director who, first chance he got, rushed to shoot a picture on location in Monument Valley, Utah, an area frequently used by famed Hollywood director John Ford. Wenders’s double-edged attitude to the mother country of the movies expresses a common enough sentiment among the “colonials,” one often shared by the host country nationals. Hollywood’s genius for projecting the stuff that American dreams are made of may be undeniable, but non-American moviegoers can’t help but resent this invasion of their brainstem. No wonder every year at the Cannes Film Festival the cinephiles joke that the odds-on favorite for the Palme d’Or is always an anti-American film . . . from America. Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) fit the bill perfectly.

Despite onslaughts from DVD pirates and YouTube videographers, the company town for the mass production and widescreen exhibition of American values in the 20th century seems poised to dominate the market well into the 21st century. Detroit, Michigan, home to the American automobile industry, may have buckled under the competition of carmakers in Toyota City (Japan) and Sindelfingen (Germany), but Hollywood still retains its brand supremacy in popular entertainment. In part, the preeminence of the American logo is due to the intrinsic appeal of a quality package filled with gleaming treasures: individualism, freedom of movement, upward mobility, pursuits of happiness (erotic and financial), and heroes who achieve moral reform through violent means. Yet the corporate descendents of film companies 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers, and MGM have also thrived by doing what automobile manufacturers have not: adapting to new market forces and co-opting the competition. Today the Hollywood product line is not only being manufactured to overseas specifications but assembled by imported engineers.

INTERNATIONAL INFLUENCES

According to the entertainment news source Variety, more than 50 percent of Hollywood’s box-office revenues typically derive from ticket windows beyond American shores. Often the gross receipts—upwards of 70 percent in the case of transnational blockbusters like Casino Royale and The Da Vinci Code—surpass domestic tallies. That is, the bonehead antics, braindead plots, and really big explosions that, in the eyes of foreign detractors, define the worst exports result from Hollywood’s trawling for a global mandate not a domestic constituency. A simple, predictable plotline, dazzling visual effects, and monosyllabic grunts that require minimal subtitling travel better than intricate webs of narrative causality, multilayered characterizations, and fast-breaking wisecracks—which is why the ticket queues from Singapore to Senegal match up pretty well with the buying habits of American teenagers.

Of course, as an international industry hustling to sell its wares beyond American shores, Hollywood has always had an eye out for foreign customers. Even during the classic studio era, when soundstage-bound motion picture production meant that the movies were 100 percent made in America, they were never 100 percent made for America—or, more to the point, made by Americans. Then as now, the ratio of indigenous ingredients to exotic elements recorded a variable percentage, with the play-off between native-grown and foreign-born influences changing on a film-by-film basis. The most visible signs of the mix and match were the very names on the marquee, stars and directors alike. Hollywood’s only prejudice was against the foreign talent who could not be bought out. In the 1920s and 1930s, German and British directors willingly succumbed to the open checkbooks of American film producers Louis B. Mayer and David O. Selznick; lately, Mexican and Taiwanese filmmakers have proven just as susceptible to the lure of magical technology and bloated budgets. In short, perhaps what makes American movies most American is how readily the non-American strains are absorbed.

Every year-end wrap-up of the past season’s release chart offers evidence aplenty that Hollywood has long since supplanted Ellis Island as the emblematic port of entry for offshore talent angling for a piece of the action. However, the 2006 vintage, Oscar-worthy and not, offers a particularly rich sampling of immigrant success stories. It is a testimony to the assimilationist power of the medium, and the business, that the films with the deepest American roots are not always credited to an American name above the title. Consider:

The Departed: Martin Scorcese’s latest study of the rituals of American gangsterdom is a mixed-blood crossbreed: a blarney-drenched remake of the Hong Kong crime thriller Infernal Affairs (2002) recast with Hollywood stars, set among the Boston Irish, and rendered with the adrenaline energy that has been the Italian-American Scorcese’s signature touch since Mean Streets (1972). Featuring native Boston sons, actors Matt Damon and Mark Wahlberg, spitting out their distinctive accents in authentic area locations (a commitment to verisimilitude that is no minor attraction when the chameleon cities of Canada are usually hired to impersonate stateside metropolises), the film made the tribal national and (judging by its huge popularity overseas) international. Highly acclaimed, the film won the best film and best director Academy Awards this year.

Dreamgirls: Jump-cutting to another American city, Detroit, known for more melodious tribal pastimes, Bill Condon’s adaptation of the Broadway smash is the kind of bloated, bombastic, big-screen musical behemoth that only the soundstages of Hollywood could choreograph. A thinly veiled musical à clef of the rise of Motown Records and a Supremeslike girl group, the film speaks to the cost/ benefit of breaking into the Top Forty radio charts while the civil rights movement unfolds offstage. For Americans, the subtextual undertones of the success story reverberated as rhythmically as the soundtrack: Break-out star Jennifer Hudson, who was voted off the smallscreen American Idol in 2004, morphed into an authentic big-screen American idol in the musical competition that is Dreamgirls. It was a good year for musicals with an American backbeat: The family-friendly Happy Feet featured computer-animated penguins gyrating to a rock-and-roll soundtrack and inculcating environmental consciousness, in a kind of kiddie version of Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth.

Jennifer Hudson won an Academy Award for her performance in the musical Dreamgirls

Little Miss Sunshine: The most kid-centered American film of the year was also the most adult. Not unlike Wim Wenders, co-directors Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris took inspiration from Huck Finn, Jack Kerouac, and a rack of Hollywood road movies, packed a dysfunctional family into a beat-up Volkswagen van, and lit out for the territory. As always, the destination (California—where else?) is less important than the trip and the passengers along for the ride: a child beauty pageant contestant, a failed motivational speaker, a heroin-snorting grandfather, an alienated intellectual, an alienated teenager, and a wife and mother who holds it all together. Enormously popular—even beloved—stateside, Little Miss Sunshine has not fared as well overseas. Hollywood may have perfected a global positioning system of awesome efficiency, but the international swath has also meant a leveling homogeneity. A film that is too verbal, too vernacular, and too nation-specific will not cross borders profitably. Better to cultivate the transnational tagline that all true blockbusters aspire to: “a nonstop rollercoaster ride!.”

Little Miss Sunshine used a family’s cross-country road trip to chronicle their individual stories and changes in family relationships.

The Devil Wears Prada: Faring better overseas was an impeccably coiffed comedy-melodrama, directed by David Frankel from the novel by Lauren Weisberger, a Cinderella story where the princess wears not a single pair of glass slippers but a wardrobe full of high-end designer clothes. As the golden girl ingenue played by Anne Hathaway swans down the catwalk of the big screen, sleek, cool, and fabulous, the dragon lady fashionista played by Meryl Streep suffers the sad fate reserved for victims of what film critic Robin Wood diagnosed as the Rosebud syndrome: Even in America, wealth and fame is not enough without heart and character, and the soulless greedmonger will wind up like Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane (1941), dying alone, pining for the lost innocence of childhood.

Actresses Meryl Streep (left) and Anne Hathaway attend the premiere of The Devil Wears Prada in Deauville, France

Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood’s ambitious double bill was a roll of the dice unprecedented in Hollywood history, two separate films telling the same story from behind two different enemy lines. The staggered-release twinpack ranked high on the year-end “Ten Best” lists from elite film critics, but neither film was embraced by the American audience, for whom World War II is a sacred site, never an exercise in futility or moral equivalence, always a passage to celebrate.

Director Clint Eastwood is flanked by Japanese actors Ken Watanabe (left) and Tsuyoshi Ihara at the Tokyo world premier of Letters from Iwo Jima

Ironically, or appropriately, foreign-born artists read the American pulse more accurately than Eastwood, the iconic American actor-auteur. Like previous generations of fresh-off-the-boat émigrés, they brought their baggage from overseas, but quickly learned the lingo of the locals and achieved both critical and commercial renown.

The Queen: The stateside success of Stephen Frears’s modern-day costume drama reflects the longstanding American fascination with English royalty, but the byplay between a democratic ethos of feel-your-pain (Prime Minister Tony Blair) and a regal fidelity to stiff-upperlipness (Queen Elizabeth II) sides in the end with the unexpected party as each reacts to the death of Princess Diana. Counterintuitively, the queen’s traditional stoicism proves more ennobling than the easy tears shed by a celebrity culture.

Academy Award winner Helen Mirren is featured on this poster for The Queen at the Venice Film Festival.

United 93: A British director also helmed what was, for many Americans, the most resonant and wrenching experience of the year in film. Paul Greenglass’s insidethe- cockpit thriller was the first feature-length film to depict in detail the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Low-tech and cinema verité in style, unspooling virtually in real time, the film needed no star power to hit a raw nerve in the American body politic. To see United 93 in a movie theater stateside was to receive a collective gut-punch, a bracing memento mori whose impact, I suspect, did not transfer to theatrical venues beyond American shores.

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan: No discussion of the impact of guest workers in American cinema would be complete without mentioning the crudest and rudest arrival hailing from the normally well-mannered United Kingdom, the agent provocateur Sacha Baron Cohen, whose twisted road movie traces the classic frontier trajectory from East (New York) to West (in search of actress and model Pamela Anderson). Though not exactly Alexis de Tocqueville, Cohen’s clueless alter ego ends up showing Americans sides of themselves heretofore unseen, namely their limitless tolerance for the most intolerant of foreigners.

Pan’s Labyrinth, Babel, and Children of Men: The serendipity of three Mexican directors (Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón) producing three high-profile marquee titles about, respectively, a nightmarish past, an interlocking present, and a dystopian future provided the most obvious proof of the infiltration of foreign agents into Hollywood. Dubbed “The Three Amigos” by the entertainment press, the trio brought a painterly texture and a tragic sense to the glittering veneer and chirpy optimism of the American mainstream, a south-of-the-border sobriety where heroes die in the end and the world is a very nasty place impervious to human intervention. Of all the American movies from 2006, born in the USA or foreign-made, Babel, a film that belies its title, may be the best predictor of Hollywood’s multilingual, multinational future: a congenial mélange of cross-cultural elements in casting, creators, location sites (Morocco, California, Mexico, and Japan), and sensibilities. Returning a payment in kind, the foreigners are colonizing American movies.

(Left to right) Mexican filmmakers Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro, and Alejandro González Iñárritu attend New York’s Gotham Awards.