The movie industry, from individuals to major studios, is adopting more environmentally friendly practices. Robin L. Yeager is a staff writer with the Bureau of International Information Programs of the U.S. Department of State, and is the editor of Society & Values.

Making movies can be a messy business, especially from an environmental point of view. “Lights, camera, action” usually means buildings and sets are constructed for temporary use, hundreds of copies of scripts need to be printed, people must be fed and kept either warm or cool, and action scenes often require explosions and pyrotechnics. Lights need power, and everyone and everything has to be driven, flown, or otherwise moved from point to point. Even digital technology results in environmental challenges from the production, use, and disposition of specialized equipment.

As one of the largest industries in southern California, the film business has historically contributed to regional pollution levels. But many in Hollywood are committed to changing how business is conducted. Those interested in supporting the environment range from the leaders and staffs of large studios to individual actors, artists, and business people.

The Industry: Among the studio chiefs leading their companies into environmentally friendly programs are Alan Horn, president and chief operating officer of Warner Bros., and Ron Meyer, president and chief operating officer of Universal. Universal is committed to a 3 percent greenhouse gas reduction and has taken a variety of actions, such as replacing the diesel trams at their theme park with more environmentally friendly vehicles. Warner Bros. has placed emphasis on the environment for more than 14 years and has a corporate executive in charge of environmental issues. The company’s environmental projects began with waste reduction and recycling and have expanded to a comprehensive program, outlined on their Web site [www .wbenvironmental.com]. Select “Eco-Tour” from the menu to see Shelley Billik, vice president of environmental initiatives, tell the Warner Bros. story. Billik takes the viewer through many aspects of the film business, pointing out actions the studio has taken and making the case that, in addition to being good for the earth, environmental policies can be good for business.

Shelley Billik of Warner Bros. discusses the studio’s industry-leading environmental efforts.

Films: The feature film Syriana, for which George Clooney won a best supporting actor Academy Award, contained an environmental theme. The Academy Award-winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth brought former Vice President Al Gore’s presentation on global warming to a worldwide audience. Both movies challenged filmmakers to produce an entire project “carbon neutral.” Carbon neutral means that greenhouse gas emissions generated by energy consumed in the production of a project are offset by planting a number of trees or through investments in solar or other renewableenergy alternatives in an amount equivalent to the energy used on the project.

Individuals: Actors and filmmakers keep the environment in mind when choosing roles and projects, they use their status to call attention to issues, and they financially support environmental causes. The list of those active for the environment includes Robert Redford, who has received numerous honors for his efforts and whose cable television Sundance Channel recently launched The Green, a weekly block of programming dedicated to environmental issues; Leonardo DiCaprio, whose fulllength documentary project on the state of the global environment, The 11th Hour, is due out in 2007, and who has worked on a green-themed reality show and short films addressing environmental issues [www.leonard odicaprio.org]; and writer-director Paul Haggis, who backs up his professional efforts with a personal commitment to the environment, including living in a solar-powered home and driving a hybrid vehicle. Others noted for their efforts include Laurie and Larry David, Rob Reiner, Tom Hanks, Harrison Ford, Norman Lear, Cameron Diaz, Darryl Hannah, and many others.

Appropriately, during the Academy Awards ceremony in February 2007, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced that the ceremony itself was a green production and directed viewers to www.oscar.com for further information and links to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

George Clooney produced and won a best supporting actor Academy Award for his role in the film Syriana,

one of the first films to be produced in a carbon neutral manner.

Government and the Movies

Unlike many countries where the government oversees cultural programs, including cinema, the United States does not have a government office or ministry that regulates the film industry. Government, however, does interface with the movie business in several ways.

FILM PRODUCTION

In the United States, films generally come from two sources: large studios that produce many films and television programs each year and independent filmmakers, including both students and experienced filmmakers. Sometimes—through grants from universities or arts or humanities councils— independent filmmakers do receive support indirectly from funding that originated with the local, state, or federal government, but more often funding comes from private investors or through philanthropic organizations concerned with either promotion of the arts or promotion of a cause being addressed by a film.

While there is no ministry of film, there are many government offices that interact with the film industry. At the state and local levels, government film offices promote local film locations because use of their locale brings employment and other economic advantages, promotes tourist sites, or shows their region in a favorable light. These offices also help filmmakers work with the police and others to arrange for filming that impacts traffic, uses public buildings, or otherwise needs special consideration.

This film is being made with assistance of the Texas Film Commission.

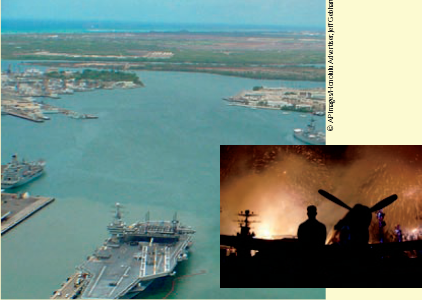

Similarly, government entities, especially the branches of the military, have offices that help coordinate filmmakers’ use of facilities, equipment, and even personnel. It would be difficult, for example, for a filmmaker to construct a make-believe aircraft carrier or to hire a cast of extras to be in the background of a movie who look like real soldiers, sailors, airmen, or marines (whose haircuts, fitness levels, and posture are often different than that of civilian actors). The military is willing to make their facilities available, within reason, for approved projects, and each branch has an office that handles these requests. Other branches of the government address requests to use public spaces and buildings, such as monuments or parks.

Many years ago, the U.S. government did produce some feature films and worked closely with Hollywood on films that would encourage public morale during wartime. However, since World War II, these programs have been eliminated through a combination of budgetary and philosophical concerns. One exception has been work carried out by government offices that, by definition, deal with external audiences, domestic or foreign. The United States Information Agency, for example, for many years produced films for exhibition to overseas audiences to complement its other educational programs. One such film, John F. Kennedy: Years of Lightning, Day of Drums, a posthumous tribute to the assassinated president, even won the 1965 Academy Award for best documentary. This agency, now a part of the U.S. Department of State, no longer produces original films.

CENSORSHIP

There have been times, especially during World War II, when national security was an issue and certain types of information were restricted from wide distribution, but, in general, the government has remained hands-off with regard to censorship. In efforts to balance free speech concerns with those of public welfare and public taste, voluntary standards enacted by the motion picture industry have resulted in a rating system (G for general audiences, R for restricted audiences, and several other categories) that industry—not government—censors apply to films, allowing viewers, parents, and theater owners to better gauge the sexual, violent, or profane-language content of a film.

FILM DISTRIBUTION

Today, with very few exceptions, films produced in the United States are distributed domestically and in other countries through commercial channels that are controlled by the market. If a film does not attract an audience, its run in the theater will be cut short and another will take its place, hoping to be a hit. In the first half of the 20th century, there was some government support to send abroad films that helped showcase American ideals. This effort has largely been reduced to a small office in the State Department that will, for example, help U.S. embassies get access to commercial films for showing to local audiences, usually in collaboration with a local sponsor, such as the ministry of culture or a university. In this way, the U.S. government supports efforts to organize film festivals and other local programs.

Through special offices of the military, filmmakers can gain access to military sites and equipment, such as those used in these scenes from the film Pearl Harbor.