History and Organization of State Judicial System

American Corner | 2013-02-01 16:20

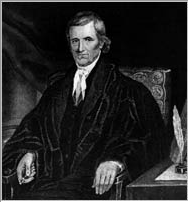

Chief Justice John Marshall, who headed the U.S. Supreme Court from 1801 to 1835, in a portrait by Alonzo Chappel (© AP Images)

(The following article is taken from the U.S. Department of State publication, Outline of the U.S. Legal System.)

Even prior to the Articles of Confederation and the writing of the U.S. Constitution in 1787, the colonies, as sovereign entities, already had written constitutions. Thus, the development of state court systems can be traced from the colonial period to the present.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF STATE COURTS

No two states are exactly alike when it comes to the organization of courts. Each state is free to adopt any organizational scheme it chooses, create as many courts as it wishes, name those courts whatever it pleases, and establish their jurisdiction as it sees fit. Thus, the organization of state courts does not necessarily resemble the clear-cut, three-tier system found at the federal level. For instance, in the federal system the trial courts are called district courts and the appellate tribunals are known as circuit courts. However, in well over a dozen states the circuit courts are trial courts. Several other states use the term superior court for their major trial courts. Perhaps the most bewildering situation is found in New York, where the major trial courts are known as supreme courts.

Although confusion surrounds the organization of state courts, no doubt exists about their importance. Because statutory law is more extensive in the states than at the federal level, covering everything from the most basic personal relationships to the state's most important public policies, the state courts handle a wide variety of cases, and the number of cases litigated annually in the state courts far exceeds those decided in the federal tribunals.

The Colonial Period

During the colonial period, political power was concentrated in the hands of the governor appointed by the king of England. Because the governors performed executive, legislative, and judicial functions, an elaborate court system was not necessary.

The lowest level of the colonial judiciary consisted of local judges called justices of the peace or magistrates. They were appointed by the colony's governor. At the next level in the system were the county courts, the general trial courts for the colonies. Appeals from all courts were taken to the highest level – the governor and his council. Grand and petit juries were also introduced during this period and remain prominent features of the state judicial systems.

By the early 18th century the legal profession had begun to change. Lawyers trained in the English Inns of Court became more numerous, and as a consequence colonial court procedures were slowly replaced by more sophisticated English common law.

Early State Courts

Following the American Revolution (1775-83), the powers of the government were not only taken over by legislative bodies but also greatly reduced. The former colonists were not eager to see the development of a large, independent judiciary given that many of them harbored a distrust of lawyers and the common law. The state legislatures carefully watched the courts and in some instances removed judges or abolished specific courts because of unpopular decisions.

Increasingly, a distrust of the judiciary developed as courts declared legislative actions unconstitutional. Conflicts between legislatures and judges, often stemming from opposing interests, became more prominent. Legislators seemed more responsive to policies that favored debtors, whereas courts generally reflected the views of creditors. These differences were important because "out of this conflict over legislative and judicial power...the courts gradually emerged as an independent political institution," according to David W. Neubauer in America's Courts and the Criminal Justice System.

Modern State Courts

From the Civil War (1861-65) to the early 20th century, the state courts were beset by other problems. Increasing industrialization and the rapid growth of urban areas created new types of legal disputes and resulted in longer and more complex court cases. The state court systems, largely fashioned to handle the problems of a rural, agrarian society, were faced with a crisis of backlogs as they struggled to adjust.

One response was to create new courts to handle the increased volume of cases. Often, courts were piled on top of each other. Another strategy was the addition of new courts with jurisdiction over a specific geographic area. Still another response was to create specialized courts to handle one particular type of case. Small claims courts, juvenile courts, and domestic relations courts, for example, became increasingly prominent.

The largely unplanned expansion of state and local courts to meet specific needs led to a situation many have referred to as fragmentation. A multiplicity of trial courts was only one aspect of fragmentation, however. Many courts had very narrow jurisdiction. Furthermore, the jurisdictions of the various courts often overlapped.

Early in the 20th century, people began to speak out against the fragmentation in the state court systems. The program of reforms that emerged in response is generally known as the court unification movement. The first well-known legal scholar to speak out in favor of court unification was Roscoe Pound, dean of the Harvard Law School. Pound and others called for the consolidation of trial courts into a single set of courts or two sets of courts, one to hear major cases and one to hear minor cases.

A good deal of opposition has arisen to court unification. Many trial lawyers who are in court almost daily become accustomed to existing court organizations and, therefore, are opposed to change. Also, judges and other personnel associated with the courts are sometimes opposed to reform. Their opposition often grows out of fear – of being transferred to new courts, of having to learn new procedures, or of having to decide cases outside their area of specialization. The court unification movement, then, has not been as successful as many would like. On the other hand, proponents of court reform have secured victories in some states.

STATE COURT ORGANIZATION

Some states have moved in the direction of a unified court system, whereas others still operate with a bewildering complex of courts with overlapping jurisdiction. The state courts may be divided into four general categories or levels: trial courts of limited jurisdiction, trial courts of general jurisdiction, intermediate appellate courts, and courts of last resort.

Trial Courts of Limited Jurisdiction

Trial courts of limited jurisdiction handle the bulk of litigation in the United States each year and constitute about 90 percent of all courts. They have a variety of names: justice of the peace courts, magistrate courts, municipal courts, city courts, county courts, juvenile courts, domestic relations courts, and metropolitan courts, to name the more common ones.

The jurisdiction of these courts is limited to minor cases. In criminal matters, for example, state courts deal with three levels of violations: infractions (the least serious), misdemeanors (more serious), and felonies (the most serious). Trial courts of limited jurisdiction handle infractions and misdemeanors. They may impose only limited fines (usually no more than $1,000) and jail sentences (generally no more than one year). In civil cases these courts are usually limited to disputes under a certain amount, such as $500. In addition, these types of courts are often limited to certain kinds of matters: traffic violations, domestic relations, or cases involving juveniles, for example.

Another difference from trial courts of general jurisdiction is that in many instances these limited courts are not courts of record. Since their proceedings are not recorded, appeals of their decisions usually go to a trial court of general jurisdiction for what is known as a trial "de novo" (new trial). Yet another distinguishing characteristic of trial courts of limited jurisdiction is that the presiding judges of such courts are often not required to have any formal legal training.

Many of these courts suffer from a lack of resources. Often, they have no permanent courtroom, meeting instead in grocery stores, restaurants, or private homes. Clerks are frequently not available to keep adequate records. The results are informal proceedings and the processing of cases on a mass basis. Full-fledged trials are rare and cases are disposed of quickly.

Finally, trial courts of limited jurisdiction are used in some states to handle preliminary matters in felony criminal cases. They often hold arraignments, set bail, appoint attorneys for indigent defendants, and conduct preliminary examinations. The case is then transferred to a trial court of general jurisdiction for such matters as hearing pleas, holding trials, and sentencing.

Trial Courts of General Jurisdiction

Most states have one set of major trial courts that handle the more serious criminal and civil cases. In addition, in many states, special categories – such as juvenile criminal offenses, domestic relations cases, and probate cases – are under the jurisdiction of the general trial courts.

In most states these courts also have an appellate function. They hear appeals in certain types of cases that originate in trial courts of limited jurisdiction. These appeals are often heard in a trial de novo or tried again in the court of general jurisdiction.

General trial courts are usually divided into judicial districts or circuits. Although the practice varies by state, the general rule is to use existing political boundaries, such as a county or a group of counties, in establishing the district or circuit. In rural areas the judge may ride circuit and hold court in different parts of the territory according to a fixed schedule. In urban areas, however, judges hold court in a prescribed place throughout the year. In larger counties the group of judges may be divided into specializations. Some may hear only civil cases; others try criminal cases exclusively.

The courts at this level have a variety of names. The most common are district, circuit, and superior. The judges at this level are required by law in all states to have law degrees. These courts also maintain clerical help because they are courts of record.

U.S. courts often settle passionately contested issues such as affirmative action in higher education. (© AP Images)

Intermediate Appellate Courts

The intermediate appellate courts are relative newcomers to the state judicial scene. Only 13 such courts existed in 1911, whereas 39 states had created them by 1995. Their basic purpose is to relieve the workload of the state's highest court.

In most instances these courts are called courts of appeals, although other names are occasionally used. Most states have one court of appeals with statewide jurisdiction. The size of intermediate courts varies from state to state. The court of appeals in Alaska, for example, has only three judges. At the other extreme, Texas has 80 courts of appeals judges. In some states the intermediate appeals courts sit en banc, whereas in other states they sit in permanent or rotating panels.

Courts of Last Resort

Every state has a court of last resort. The states of Oklahoma and Texas have two highest courts. Both states have a supreme court with jurisdiction limited to appeals in civil cases and a court of criminal appeals for criminal cases. Most states call their highest courts supreme courts; other designations are the court of appeals (Maryland and New York), the supreme judicial court (Maine and Massachusetts), and the supreme court of appeals (West Virginia). The courts of last resort range in size from three to nine judges (or justices in some states). They typically sit en banc and usually, although not necessarily, convene in the state capital.

The highest courts have jurisdiction in matters pertaining to state law and are, of course, the final arbiters in such matters. In states that have intermediate appellate courts, the supreme court's cases come primarily from these mid-level courts. In this situation the high court typically is allowed to exercise discretion in deciding which cases to review. Thus, it is likely to devote more time to cases that deal with the important policy issues of the state. When there is no intermediate court of appeals, cases generally go to the state's highest court on a mandatory review basis.

In most instances, then, the state courts of last resort resemble the U.S. Supreme Court in that they have a good deal of discretion in determining which cases will occupy their attention. Most state supreme courts also follow procedures similar to those of the U.S. Supreme Court. That is, when a case is accepted for review the opposing parties file written briefs and later present oral arguments. Then, upon reaching a decision, the judges issue written opinions explaining that decision.

Juvenile Courts

Americans are increasingly concerned about the handling of cases involving juveniles, and states have responded to the problem in a variety of ways. Some have established a statewide network of courts specifically to handle matters involving juveniles. Two states – Rhode Island and South Carolina – have family courts, which handle domestic relations matters as well as those involving juveniles.

The most common approach is to give one or more of the state's limited or general trial courts jurisdiction to handle situations involving juveniles. In Alabama, for example, the circuit courts (trial courts of general jurisdiction) have jurisdiction over juvenile matters. In Kentucky, however, exclusive juvenile jurisdiction is lodged in trial courts of limited jurisdiction – the district courts.

Finally, some states apportion juvenile jurisdiction among more than one court. The state of Colorado has a juvenile court for the city of Denver and has given jurisdiction over juveniles to district courts (general trial courts) in the other areas of the state.

Also, some variation exists among the states as to when jurisdiction belongs to an adult court. States set a standard age at which defendants are tried in an adult court. In addition, many states require that more youthful offenders be tried in an adult court if special circumstances are present. In Illinois, for instance, the standard age at which juvenile jurisdiction transfers to adult courts is 17. The age limit drops to 15, however, for first-degree murder, aggravated criminal sexual assault, armed robbery, robbery with a firearm, and unlawful use of weapons on school grounds.

ADMINISTRATIVE AND STAFF SUPPORT IN THE STATE JUDICIARY

The daily operation of the federal courts requires the efforts of many individuals and organizations. This is no less true for the state court systems.

Magistrates

State magistrates, who may also be known in some states as commissioners or referees, are often used to perform some of the work in the early stages of civil and criminal case processing. In this way they are similar to U.S. magistrate judges. In some jurisdictions they hold bond hearings and conduct preliminary investigations in criminal cases. They are also authorized in some states to make decisions in minor cases.

Law Clerks

In the state courts, law clerks are likely to be found, if at all, in the intermediate appellate courts and courts of last resort. Most state trial courts do not utilize law clerks, and they are practically unheard of in local trial courts of limited jurisdiction. As at the national level, some law clerks serve individual judges while others serve an entire court as a staff attorney.

Administrative Office of the Courts

Every state now has an administrative office of courts or a similarly titled agency that performs a variety of administrative tasks for that state's court system. Among the tasks more commonly associated with administrative offices are budget preparation, data processing, facility management, judicial education, public information, research, and personnel management. Juvenile and adult probation are the responsibility of administrative offices in a few states, as is alternative dispute resolution.

Court Clerks and Court Administrators

The clerk of the court has traditionally handled the day-to-day routines of the court. This includes making courtroom arrangements, keeping records of case proceedings, preparing orders and judgments resulting from court actions, collecting court fines and fees, and disbursing judicial monies. In the majority of states these officials are elected and may be referred to by other titles.

The traditional clerks of court have been replaced in many areas by court administrators. In contrast to the court clerk, who traditionally managed the operations of a specific courtroom, the modern court administrator may assist a presiding judge in running the entire courthouse.

STATE COURT WORKLOAD

The lion's share of the nation's judicial business exists at the state, not the national, level. The fact that federal judges adjudicate several hundred thousand cases a year is impressive; the fact that state courts handle several million a year is overwhelming, even if the most important cases are handled at the federal level. While justice of the peace and magistrate courts at the state level handle relatively minor matters, some of the biggest judgments in civil cases are awarded by ordinary state trial court juries.

The National Center for State Courts has compiled figures on the caseloads of state courts of last resort and intermediate appellate courts in 1998. In all, some 261,159 mandatory cases and discretionary petitions were filed in the state appellate courts. Reliable data on cases filed in the state trial courts are harder to come by. Still, the center does an excellent job of tracking figures for states' trial courts. In 1998, 17,252,940 cases were filed in the general jurisdiction and limited jurisdiction courts. As with the federal courts, the vast majority of the cases are civil, although the criminal cases often receive the most publicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

[Chapters 1 through 8 are adapted with permission from the book Judicial Process in America, 5th edition, by Robert A. Carp and Ronald Stidham, published by Congressional Quarterly, Inc. Copyright © 2001 Congressional Quarterly Inc. All rights reserved.]

Share this page