Gulf War(2)

USINFO | 2013-09-16 13:35

The Scud missiles targeting Israel were relatively ineffective, as firing at extreme range resulted in a dramatic reduction in accuracy and payload. Jewish Virtual Library states that a total of 74 Israelis died as a result of the Iraqi attacks: two directly and the rest from suffocation and heart attacks.[14] Approximately 230 Israelis were injured.[13] In one incident, a strike on a neighborhood in Tel Aviv caused three deaths and 96 injuries.[97] Extensive property damage was also caused, and according to Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, "Damage to general property consisted of 1,302 houses, 6142 apartments, 23 public buildings, 200 shops and 50 cars."[98] It was feared that Iraq would fire missiles filled with nerve agents or sarin. As a result, Israel's government issued gas masks to its citizens. When the first Iraqi missiles hit Israel, some people injected themselves with an antidote for nerve gas.

Aftermath of an Iraq Armed forces strike on U.S. barracks.

In response to the threat of Scuds on Israel, the U.S. rapidly sent a Patriot missile air defense artillery battalion to Israel along with two batteries of MIM-104 Patriot missiles for the protection of civilians.[99] Coalition air forces were also extensively exercised in "Scud hunts" in the Iraqi desert, trying to locate the camouflaged trucks before they fired their missiles at Israel or Saudi Arabia. On the ground, special operations forces also infiltrated Iraq, tasked with locating and destroying Scuds. Once special operations were combined with air patrols, the number of attacks fell sharply, then increased slightly as Iraqi forces adjusted to Coalition tactics.The Royal Netherlands Air Force also deployed Patriot missiles to counter the Scud threat. The Dutch Defense Ministry later stated that the military use of the Patriot missile system was largely ineffective, but its psychological value was high, even though the Patriot missiles caused far more casualties and property damage than the Scuds themselves did.[100][101] It has been suggested that the sturdy construction techniques used in Israeli cities, coupled with the fact that Scuds were only launched at night, played an important role in limiting the number of casualties from Scud attacks.[13]

As the Scud attacks continued, the Israelis grew increasingly impatient, and considered taking unilateral military action against Iraq. After the attack on Ramat Gan, the Israelis warned that unless the U.S. stopped the Scuds, Israel would. At one point, Israeli commandos were loaded onto helicopters prepared to fly into Iraq, but the mission was called off after a phone call from U.S. Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, reporting on the extent of Coalition efforts to destroy Scuds and emphasizing that Israeli intervention could endanger U.S. forces.[102]

In addition to the attacks on Israel, 47 Scud missiles were fired into Saudi Arabia, and one missile was fired at Bahrain and another at Qatar. The missiles were fired at both military and civilian targets. One Saudi civilian was killed, and 78 others were injured. No casualties were reported in Bahrain or Qatar. The Saudi government issued all its citizens and expatriates with gas masks in the event of Iraq using missiles with chemical or biological warheads. The government broadcast alerts and 'all clear' messages over television to warn citizens during Scud attacks.

On 25 February 1991, a Scud missile hit a U.S. Army barracks of the 14th quartermaster Detachment, out of Greensburg, PA, stationed in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, killing 28 soldiers and injuring over 100.[15]

Battle of Khafji

Main article: Battle of Khafji

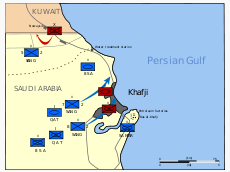

Military operations during Khafji's liberation

On 29 January, Iraqi forces attacked and occupied the lightly defended Saudi city of Khafji with tanks and infantry. The Battle of Khafji ended two days later when the Iraqis were driven back by the Saudi Arabian National Guard, supported by Qatari forces. The allied forces used extensive artillery fire.Casualties were heavy on both sides, although Iraqi forces sustained substantially more dead and captured than the allied forces. Eleven Americans were killed in two separate friendly fire incidents, an additional 14 U.S. airmen were killed when their AC-130 gunship was shot down by an Iraqi surface-to-air missile, and two U.S. soldiers were captured during the battle. Saudi and Qatari forces had a total of 18 dead. Iraqi forces in Khafji had 60–300 dead and 400 captured.

Khafji was a strategically important city immediately after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. Iraq's reluctance to commit several armored divisions to the occupation, and its subsequent use of Khafji as a launching pad into the initially lightly defended eastern Saudi Arabia was assessed by Coalition intelligence as a grave strategic error. Not only would Iraq have secured a majority of Middle Eastern oil supplies, but it would have found itself better able to threaten the subsequent U.S. deployment along superior defensive lines.[103]

Ground campaign

The Coalition forces dominated the air with their technological advantages. Coalition forces had the significant advantage of being able to operate under the protection of air supremacy that had been achieved by their air forces before the start of the main ground offensive. Coalition forces also had two key technological advantages:

- The Coalition main battle tanks, such as the U.S. M1 Abrams, British Challenger 1, and Kuwaiti M-84AB were vastly superior to the Chinese Type 69 and domestically built T-72 tanks used by the Iraqis, with crews better trained and armored doctrine better developed.

- The use of GPS made it possible for Coalition forces to navigate without reference to roads or other fixed landmarks. This, along with aerial reconnaissance, allowed them to fight a battle of maneuver rather than a battle of encounter: they knew where they were and where the enemy was, so they could attack a specific target rather than searching on the ground for enemy forces.

Main article: Liberation of Kuwait campaign

See also: Gulf War order of battle ground campaign

U.S. decoy attacks by air attacks and naval gunfire the night before Kuwait's liberation were designed to make the Iraqis believe the main Coalition ground attack would focus on central Kuwait.

For months, American units in Saudi Arabia had been under almost constant Iraqi artillery fire, as well as threats from Scud missile or chemical attacks. On 24 February 1991, the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions, and the 1st Light Armored Infantry Battalion crossed into Kuwait and headed toward Kuwait City. They encountered trenches, barbed wire, and minefields. However, these positions were poorly defended, and were overrun in the first few hours. Several tank battles took place, but apart from that, Coalition troops encountered minimal resistance, as most Iraqi troops surrendered. The general pattern was that the Iraqis would put up a short fight before surrendering. However, Iraqi air defenses shot down nine U.S. aircraft. Meanwhile, forces from Arab states advanced into Kuwait from the east, encountering little resistance and suffering few casualties.

Despite the successes of Coalition forces, it was feared that the Iraqi Republican Guard would escape into Iraq before it could be destroyed. It was decided to send British armored forces into Kuwait fifteen hours ahead of schedule, and to send U.S. forces after the Republican Guard. The Coalition advance was preceded by a heavy artillery and rocket barrage, after which 150,000 troops and 1,500 tanks began their advance. Iraqi forces in Kuwait counterattacked against U.S. troops, acting on a direct order from Saddam himself. Despite the intense combat, the Americans repulsed the Iraqis and continued to advance towards Kuwait City.

Kuwaiti forces were tasked with liberating the city. Iraqi troops offered only light resistance. The Kuwaitis lost one soldier killed and one plane shot down, and quickly liberated the city. On 27 February, Saddam ordered a retreat from Kuwait, and President Bush declared it liberated. However, an Iraqi unit atKuwait International Airport appeared not to have gotten the message, and fiercely resisted. U.S. Marines had to fight for hours before securing the airport, after which Kuwait was declared secure. After four days of fighting, Iraqi forces were expelled from Kuwait. As part of a scorched earth policy, they set fireto nearly 700 oil wells, and placed land mines around the wells to make extinguishing the fires more difficult.

Initial moves into Iraq

Iraqi T-62 knocked out by 3rd Armored Divisionfire

The first units to move into Iraq were three patrols of the British Special Air Service's B squadron, call signs Bravo One Zero, Bravo Two Zero, and Bravo Three Zero, in late January. These eight-man patrols landed behind Iraqi lines to gather intelligence on the movements of Scud mobile missile launchers, which couldn't be detected from the air, as they were hidden under bridges and camouflage netting during the day.[105] Other objectives included the destruction of the launchers and their fiber-optic communications arrays that lay in pipelines and relayed coordinates to the TEL operators that were launching attacks against Israel. The operations were designed to prevent any possible Israeli intervention. Due to lack of sufficient ground cover to carry out their assignment, One Zero and Three Zero abandoned their operations, while Two Zero remained, and was later compromised, with only Sergeant Chris Ryan escaping to Syria.

Elements of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Battalion 5th Cavalry of the 1st Cavalry Division of the U.S. Army performed a direct attack into Iraq on 15 February 1991, followed by one in force on 20 February that led directly through 7 Iraqi divisions which were caught off guard.[citation needed] From 15–20 February, the Battle of Wadi Al-Batin took place inside Iraq; this was the first of two attacks by 1 Battalion 5th Cavalry of the 1st Cavalry Division. It was a feint attack, designed to make the Iraqis think that a Coalition invasion would take place from the south. The Iraqis fiercely resisted, and the Americans eventually withdrew as planned back into the Wadi Al-Batin. Three U.S. soldiers were killed and nine wounded as well with only 1 M-2 IFV turret destroyed, but they had taken 40 prisoners and destroyed five tanks, and successfully deceived the Iraqis. This attack led the way for the XVIII Airborne Corps to sweep around behind the 1st Cav and attack Iraqi forces to the west. On 22 February 1991, Iraq agreed to a Soviet-proposed ceasefire agreement. The agreement called for Iraq to withdraw troops to pre-invasion positions within six weeks following a total cease-fire, and called for monitoring of the cease-fire and withdrawal to be overseen by the U.N. Security Council.

The Coalition rejected the proposal, but said that retreating Iraqi forces wouldn't be attacked,and gave twenty-four hours for Iraq to begin withdrawing forces. On 23 February, fighting resulted in the capture of 500 Iraqi soldiers. On 24 February, British and American armored forces crossed the Iraq-Kuwait border and entered Iraq in large numbers, taking hundreds of prisoners. Iraqi resistance was light, and 4 Americans were killed.[106]

Coalition forces enter Iraq

Shortly afterwards, the U.S. VII Corps, in full strength and spearheaded by the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, launched an armored attack into Iraq early on 24 February, just to the west of Kuwait, taking Iraqi forces by surprise. Simultaneously, the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps launched a sweeping “left-hook” attack across southern Iraq's largely undefended desert, led by the U.S. 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment and the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized). This movement's left flank was protected by France's 6th Light Armoured Division Daguet.

The French force quickly overcame Iraq's 45th Infantry Division, suffering light casualties and taking a large number of prisoners, and took up blocking positions to prevent an Iraqi counter-attack on the Coalition's flank. The movement's right flank was protected by the United Kingdom's 1st Armoured Division. Once the allies had penetrated deep into Iraqi territory, they turned eastward, launching a flank attack against the elite Republican Guard before it could escape. The Iraqis resisted fiercely from dug-in positions and stationary vehicles, and even mounted armored charges.

Unlike many previous engagements, the destruction of the first Iraqi tanks did not result in a mass surrender. The Iraqis suffered massive losses and lost dozens of tanks and vehicles, while U.S. casualties were comparatively low, with a single Bradley knocked out. Coalition forces pressed another ten kilometers into Iraqi territory, and captured their objective within three hours. They took 500 prisoners and inflicted heavy losses, defeating Iraq's 26th Infantry Division. A U.S. soldier was killed by an Iraqi land mine, another five by friendly fire, and thirty wounded during the battle. Meanwhile, British forces attacked Iraq's Medina Division and a major Republican Guard logistics base. In nearly two days of some of the war's most intense fighting, the British destroyed 40 enemy tanks and captured a division commander.

Meanwhile, U.S. forces attacked the village of Al Busayyah, meeting fierce resistance. They suffered no casualties, but destroyed a considerable amount of military hardware and took prisoners.

On 25 February 1991, Iraqi forces fired a Scud missile at an American barracks in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The missile attack killed 28 U.S. military personnel.[107]

The Coalition's advance was much swifter than U.S. generals had expected. On 26 February, Iraqi troops began retreating from Kuwait, after they had set itsoil fields on fire (737 oil wells were set on fire). A long convoy of retreating Iraqi troops formed along the main Iraq-Kuwait highway. Although they were retreating, this convoy was bombed so extensively by Coalition air forces that it came to be known as the Highway of Death. Hundreds of Iraqi troops were killed. American, British, and French forces continued to pursue retreating Iraqi forces over the border and back into Iraq, eventually moving to within 150 miles (240 km) of Baghdad before withdrawing back to Iraq's border with Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

One hundred hours after the ground campaign started, on 28 February, President Bush declared a ceasefire, and he also declared that Kuwait had been liberated.

Post-war military analysis

Although it was said in Western media at the time that Iraqi troops numbered approximately 545,000 to 600,000, most experts today believe that the Iraqi Army's qualitative and quantitative descriptions were exaggerated, as they included both temporary and auxiliary support elements. Many Iraqi troops were young, under-resourced, and poorly trained conscripts.

The Coalition committed 540,000 troops, and a further 100,000 Turkish troops were deployed along the Turkish-Iraqi border. This caused a significant force dilution of Iraq's military by forcing it to deploy its forces along all its borders. This allowed the main thrust by the U.S. to possess not only a significant technological advantage, but also a numerical superiority.

The widespread support for Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War equipped Iraq with military equipment from most major world arms dealers. This resulted in a lack of standardization in this large heterogeneous force, which additionally suffered from poor training and poor motivation. The majority of Iraqi armored forces still used old Chinese Type 59s andType 69s, Soviet-made T-55s from the 1950s and 1960s, and poor quality Asad Babil tanks (domestically assembled tank based on Polish T-72 hulls with other parts of mixed origin). These machines were not equipped with up-to-date equipment, such as thermal sights or laser rangefinders, and their effectiveness in modern combat was very limited.

The Iraqis failed to find an effective countermeasure to the thermal sights and sabot rounds used by Coalition tanks. This equipment enabled them to engage and destroy Iraqi tanks from more than three times the range that Iraqi tanks could engage Coalition tanks. The Iraqi crews used old, cheap steel penetrators against the advanced Chobham Armour of the U.S. and British tanks, with ineffective results. The Iraqis also failed to exploit the advantage that could be gained from using urban warfare — fighting within Kuwait City – which could have inflicted significant casualties on the attacking forces. Urban combat reduces the range at which fighting occurs, and can negate some of the technological advantages of well-equipped forces.

The Iraqis also tried to use Soviet military doctrine, but the implementation failed due to the lack of skill of their commanders, and the preventive Coalition air strikes on communication centers and bunkers.

The end of active hostilities

Main article: 1991 uprisings in Iraq

Persian Gulf Veterans National Medal of the U.S. military.

In Coalition-occupied Iraqi territory, a peace conference was held where a ceasefire agreement was negotiated and signed by both sides. At the conference, Iraq was approved to fly armed helicopters on their side of the temporary border, ostensibly for government transit due to the damage done to civilian infrastructure. Soon after, these helicopters and much of Iraq's military were used to fight a uprising in the south. The rebellions were encouraged by an airing of "The Voice of Free Iraq" on 2 February 1991, which was broadcast from a CIA-run radio station out of Saudi Arabia. The Arabic service of the Voice of America supported the uprising by stating that the rebellion was large, and that they soon would be liberated from Saddam.[108]

In the North, Kurdish leaders took American statements that they would support an uprising to heart, and began fighting, hoping to trigger a coup d'état. However, when no U.S. support came, Iraqi generals remained loyal to Saddam and brutally crushed the Kurdish uprising. Millions of Kurds fled across the mountains to Turkey and Kurdish areas of Iran. These events later resulted in no-fly zones being established in northern and southern Iraq. In Kuwait, the Emir was restored, and suspected Iraqi collaborators were repressed. Eventually, over 400,000 people were expelled from the country, including a large number of Palestinians, due to PLOsupport of Saddam. Yasser Arafat didn't apologize for his support of Iraq, but after his death, the Fatah under Mahmoud Abbas' authority formally apologized in 2004.[109]

There was some criticism of the Bush administration, as they chose to allow Saddam to remain in power instead of pushing on to capture Baghdad and overthrowing his government. In their co-written 1998 book, A World Transformed, Bush and Brent Scowcroft argued that such a course would have fractured the alliance, and would have had many unnecessary political and human costs associated with it.

In 1992, the U.S. Defense Secretary during the war, Dick Cheney, made the same point:

I would guess if we had gone in there, we would still have forces in Baghdad today. We'd be running the country. We would not have been able to get everybody out and bring everybody home. And the final point that I think needs to be made is this question of casualties. I don't think you could have done all of that without significant additional U.S. casualties, and while everybody was tremendously impressed with the low cost of the (1991) conflict, for the 146 Americans who were killed in action and for their families, it wasn't a cheap war. And the question in my mind is, how many additional American casualties is Saddam (Hussein) worth? And the answer is, not that damned many. So, I think we got it right, both when we decided to expel him from Kuwait, but also when the President made the decision that we'd achieved our objectives and we were not going to go get bogged down in the problems of trying to take over and govern Iraq.[110]

— Dick Cheney

Instead of a greater involvement of its own military, the U.S. hoped that Saddam would be overthrown in an internal coup d'état. The CIA used its assets in Iraq to organize a revolt, but the Iraqi government defeated the effort.

On 10 March 1991, 540,000 U.S. troops began moving out of the Persian Gulf.

Coalition involvement

Coalition troops from Egypt, Syria, Oman, France and Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm.

Main article: Coalition of the Gulf WarCoalition members included Argentina, Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Egypt, France, Greece, Honduras, Hungary, Italy, Kuwait, Malaysia, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Niger, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America.[111]

Germany and Japan provided financial assistance and donated military hardware, but didn't send direct military assistance. This later became known ascheckbook diplomacy.

United Kingdom

British Army Challenger 1 main battle tank during Operation Desert Storm.

The United Kingdom committed the largest contingent of any European state that participated in the war's combat operations.Operation Granby was the code name for the operations in the Persian Gulf. British Army regiments (mainly with the 1st Armoured Division), Royal Air Force squadrons and Royal Navy vessels were mobilized in the Gulf. The Royal Air Force, using various aircraft, operated from airbases in Saudi Arabia. Almost 2,500 armored vehicles and 53,462 troops were shipped for action.Chief Royal Navy vessels deployed to the Gulf included Broadsword-class frigates, and Sheffield-class destroyers, other R.N. and R.F.A. ships were also deployed. The light aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal was deployed to the Mediterranean Sea.Special operations forces were deployed in the form of several SAS squadrons.

France

The second largest European contingent was from France, which committed 18,000 troops.[111] Operating on the left flank of the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps, the main French Army force was the 6th Light Armoured Division, including troops from the French Foreign Legion. Initially, the French operated independently under national command and control, but coordinated closely with the Americans (via CENTCOM) and Saudis. In January, the Division was placed under the tactical control of the XVIII Airborne Corps. France also deployed several combat aircraft and naval units. The French called their contribution Opération Daguet.

Canada

Canadian CF-18 Hornetsparticipated in combat during the Gulf War.

See also: Operation FRICTIONCanada was one of the first countries to condemn Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, and it quickly agreed to join the U.S.-led coalition. In August 1990, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney committed the Canadian Forces to deploy a Naval Task Group. The destroyers HMCS Terra Nova and HMCS Athabaskan joined the maritime interdiction force supported by the supply shipHMCS Protecteur in Operation Friction. The Canadian Task Group led the Coalition's maritime logistics forces in the Persian Gulf. A fourth ship, HMCS Huron, arrived in-theater after hostilities had ceased and was the first allied ship to visit Kuwait.

Following the U.N.-authorized use of force against Iraq, the Canadian Forces deployed a CF-18 Hornet and CH-124 Sea King squadron with support personnel, as well as a field hospital to deal with casualties from the ground war. When the air war began, the CF-18s were integrated into the Coalition force and were tasked with providing air cover and attacking ground targets. This was the first time since the Korean War that Canada's military had participated in offensive combat operations. The only CF-18 Hornet to record an official victory during the conflict was an aircraft involved in the beginning of the Battle of Bubiyan against the Iraqi Navy.[112]

The Canadian Commander in the Middle East was Commodore Kenneth J. Summers.

Australia

Main article: Australian contribution to the 1991 Gulf War

Australia contributed a Naval Task Group, which formed part of the multi-national fleet in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman, under Operation Damask. In addition, medical teams were deployed aboard a U.S. hospital ship, and a naval clearance diving team took part in de-mining Kuwait’s port facilities following the end of combat operations.

While the Australian forces didn't see combat, they did play a significant role in enforcing the sanctions put in place against Iraq following Kuwait's invasion, as well as other small support contributions to Operation Desert Storm. Following the war's end, Australia deployed a medical unit on Operation Habitat to northern Iraq as part of Operation Provide Comfort.

Argentina

Argentina participated in the war through the Operation Bishop, sending the destroyer ARA Almirante Brown (D-10) and the corvette ARA Spiro (P-43). Later, that fleet was replaced by the corvette ARA Rosales (P-42) and transport ship ARA Bahía San Blas (B-4).

The increased importance of air attacks from both warplanes and cruise missiles led to controversy over the number of civilian deaths caused during the war's initial stages. Within the war's first 24 hours, more than 1,000 sorties were flown, many against targets in Baghdad. The city was the target of heavy bombing, as it was the seat of power for Saddam and the Iraqi forces'command and control. This ultimately led to civilian casualties.

In one noted incident, two USAF stealth planes bombed a bunker in Amiriyah, causing the deaths of 408 Iraqi civilians who were in the shelter.[113] Scenes of burned and mutilated bodies were subsequently broadcast, and controversy arose over the bunker's status, with some stating that it was a civilian shelter, while others contended that it was a center of Iraqi military operations, and that the civilians had been deliberately moved there to act as human shields.

An investigation by Beth Osborne Daponte estimated total civilian fatalities at about 3,500 from bombing, and some 100,000 from the war's other effects.[114][115][116]

Iraqi

The exact number of Iraqi combat casualties is unknown, but is believed to have been heavy. Some estimate that Iraq sustained between 20,000 and 35,000 fatalities.[114] A report commissioned by the U.S. Air Force, estimated 10,000–12,000 Iraqi combat deaths in the air campaign, and as many as 10,000 casualties in the ground war.[117] This analysis is based on Iraqi prisoner of war reports.

Saddam's government gave high civilian casualty figures in order to draw support from Islamic countries. The Iraqi government claimed that 2,300 civilians died during the air campaign. [118]According to the Project on Defense Alternatives study, 3,664 Iraqi civilians, and between 20,000 and 26,000 military personnel, were killed in the conflict, while 75,000 Iraqi soldiers were wounded.[119]

Coalition

| Coalition troops killed by country | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Total |

Enemy action |

Accident |

Friendly fire |

Ref |

| United States | 294 | 114 | 145 | 35 | [120] |

| Senegal | 92 | 92 | [121] | ||

| United Kingdom | 47 | 38 | 9 | [122] | |

| Saudi Arabia | 24 | 18 | 6 | .[123][124] | |

| France | 9 | 9 | [120] | ||

| United Arab Emirates | 6 | 6 | [125] | ||

| Qatar | 3 | 3 | [120] | ||

| Syria | 2 | [126] | |||

| Egypt | 11 | 5 | .[127][128] | ||

| Kuwait | 1 | 1 | [129] | ||

The DoD reports that U.S. forces suffered 148 battle-related deaths (35 to friendly fire[130]), with one pilotlisted as MIA (his remains were found and identified in August 2009). A further 145 Americans died in non-combat accidents.[120] The U.K. suffered 47 deaths (9 to friendly fire, all by U.S. forces), France 2,[120] and the other countries, not including Kuwait, suffered 37 deaths (18 Saudis, 1 Egyptian, 6 UAE, and 3 Qataris).[120] At least 605 Kuwaiti soldiers were still missing 10 years after their capture.[131]

The largest single loss of life among Coalition forces happened on 25 February 1991, when an Iraqi Al Hussein missile hit a U.S. military barrack in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, killing 28 U.S. Army Reservists from Pennsylvania. In all, 190 Coalition troops were killed by Iraqi fire during the war, 113 of whom were American, out of a total of 358 Coalition deaths. Another 44 soldiers were killed, and 57 wounded, by friendly fire. 145 soldiers died of exploding munitions, or non-combat accidents.[132]

The largest accident among Coalition forces happened on 21 March 1991, a Royal Saudi Air Force C-130H crashed in heavy smoke on approach to Ras Al-Mishab Airport, Saudi Arabia. 92 Senegalese soldiers were killed.

The number of Coalition wounded in combat seems to have been 776, including 458 Americans.[133]

190 Coalition troops were killed by Iraqi combatants, the rest of the 379 Coalition deaths being from friendly fire or accidents. This number was much lower than expected. Among the American dead were three female soldiers.

Friendly fire

While the death toll among Coalition forces engaging Iraqi combatants was very low, a substantial number of deaths were caused by accidental attacks from other Allied units. Of the 148 U.S. troops who died in battle, 24% were killed by friendly fire, a total of 35 service personnel.[134] A further 11 died in detonations of allied munitions. Nine British military personnel were killed in a friendly fire incident when a USAF A-10 Thunderbolt II destroyed a group of two Warrior IFVs.

Main article: Gulf War syndrome

Many returning Coalition soldiers reported illnesses following their action in the war, a phenomenon known as Gulf War syndrome or Gulf War illness. There has been widespread speculation and disagreement about the causes of the illness and the reported birth defects. Some factors considered as possibilities include exposure to depleted uranium, chemical weapons, anthrax vaccinesgiven to deploying soldiers, and/or infectious diseases. Major Michael Donnelly, a USAF officer during the War, helped publicize the syndrome and advocated for veterans' rights in this regard.

Effects of depleted uranium

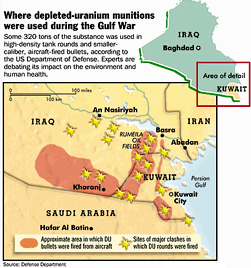

Approximate area and major clashes in which DU rounds were used.

Main article: Depleted uranium#Health considerationsDepleted uranium was used in the war in tank kinetic energy penetrators and 20–30 mm cannon ordnance. DU is a pyrophoric, genotoxic, and teratogenicheavy metal. Many have cited its use during the war as a contributing factor to a number of instances of health issues in the conflict's veterans and surrounding civilian populations. However, scientific opinion on the risk is mixed.[135][136]

Highway of Death

Main article: Highway of Death

On the night of 26–27 February 1991, some Iraqi forces began leaving Kuwait on the main highway north of Al Jahra in a column of some 1,400 vehicles. A patrolling E-8 Joint STARS aircraft observed the retreating forces and relayed the information to the DDM-8 air operations center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[137] These vehicles and the retreating soldiers were subsequently attacked, resulting in a 60 km stretch of highway strewn with debris—the Highway of Death.

Chuck Horner, Commander of U.S. and allied air operations has written:

[By February 26], the Iraqis totally lost heart and started to evacuate occupied Kuwait, but airpower halted the caravan of Iraqi Army and plunderers fleeing toward Basra. This event was later called by the media "The Highway of Death." There were certainly a lot of dead vehicles, but not so many dead Iraqis. They'd already learned to scamper off into the desert when our aircraft started to attack. Nevertheless, some people back home wrongly chose to believe we were cruelly and unusually punishing our already whipped foes.

[...]

By February 27, talk had turned toward terminating the hostilities. Kuwait was free. We were not interested in governing Iraq. So the question became "How do we stop the killing."[138]

Bulldozer assault

Another incident during the war highlighted the question of large-scale Iraqi combat deaths. This was the "bulldozer assault", wherein two brigades from the U.S. 1st Infantry Division (Mechanized) were faced with a large and complex trench network, as part of the heavily fortified "Saddam Hussein Line". After some deliberation, they opted to use anti-mine plows mounted ontanks and combat earthmovers to simply plow over and bury alive the defending Iraqi soldiers. One newspaper story reported that U.S. commanders estimated thousands of Iraqi soldiers surrendered, escaping live burial during the two-day assault 24–26 February 1991. Patrick Day Sloyan of Newsday reported, "Bradley Fighting Vehicles and Vulcan armored carriers straddled the trench lines and fired into the Iraqi soldiers as the tanks covered them with mounds of sand. 'I came through right after the lead company,' [Col. Anthony] Moreno said. 'What you saw was a bunch of buried trenches with peoples' arms and things sticking out of them...'"[139] However, after the war, the Iraqi government claimed to have found only 44 bodies.[140] In his book The Wars Against Saddam,John Simpson alleges that U.S. forces attempted to cover up the incident.[141] After the incident, the commander of the 1st Brigade said: "I know burying people like that sounds pretty nasty, but it would be even nastier if we had to put our troops in the trenches and clean them out with bayonets."[139]

1991 Palestinian exodus from Kuwait

Main article: Palestinian expulsion from Kuwait

Kuwait's expulsion policy was a response to PLO leader Yasser Arafat's alignment with Saddam, who had earlier invaded Kuwait. Prior to the war, Palestinians made up about 30% of Kuwait's 2 million residents.[142] The exodus took place during one week in March 1991, following Kuwait's liberation from Iraqi occupation. Kuwait expelled about 300,000 Palestinians from its territory,[143] By 2011, many had returned to Kuwait and today the number of Palestinians living in Kuwait is 90,000.[144]

Coalition bombing of Iraq's civilian infrastructure

In the 23 June 1991 edition of The Washington Post, reporter Bart Gellman wrote: "Many of the targets were chosen only secondarily to contribute to the military defeat of [Iraq]. . . . Military planners hoped the bombing would amplify the economic and psychological impact of international sanctions on Iraqi society. . . . They deliberately did great harm to Iraq's ability to support itself as an industrial society. . . ."[145] In the Jan/Feb 1995 edition of Foreign Affairs, French diplomat Eric Rouleau wrote: "[T]he Iraqi people, who were not consulted about the invasion, have paid the price for their government's madness. . . . Iraqis understood the legitimacy of a military action to drive their army from Kuwait, but they have had difficulty comprehending the Allied rationale for using air power to systematically destroy or cripple Iraqi infrastructure and industry: electric power stations (92 percent of installed capacity destroyed), refineries (80 percent of production capacity), petrochemical complexes, telecommunications centers (including 135 telephone networks), bridges (more than 100), roads, highways, railroads, hundreds of locomotives and boxcars full of goods, radio and television broadcasting stations, cement plants, and factories producing aluminum, textiles, electric cables, and medical supplies."[146]However, the U.N. subsequently spent billions rebuilding hospitals, schools, and water purification facilities throughout the country.[147]

Abuse of Coalition POWs

During the conflict, Coalition aircrew shot down over Iraq were displayed as prisoners of war on TV, most with visible signs of abuse. Amongst several testimonies to poor treatment,[148] Royal Air Force Tornado crew John Nichol and John Peters have both alleged that they were tortured during this time.[149][150] Nichol and Peters were forced to make statements against the war in front of television cameras. Members of British Special Air Service Bravo Two Zero were captured while providing information about an Iraqi supply line of Scud missiles to Coalition forces. Only one,Chris Ryan, evaded capture while the group's other surviving members were violently tortured.[151] Flight surgeon (later General) Rhonda Cornum was raped by one of her captors[152] after the Black Hawk she was riding in was shot down while searching for a downed F-16 pilot.

Operation Southern Watch

Main article: Operation Southern Watch

Since the war, the U.S. has had a continued presence of 5,000 troops stationed in Saudi Arabia – a figure that rose to 10,000 during the 2003 conflict in Iraq.[153] Operation Southern Watch enforced the no-fly zones over southern Iraq set up after 1991; oil exports through the Persian Gulf's shipping lanes were protected by the Bahrain-based U.S. Fifth Fleet.

Since Saudi Arabia houses Mecca and Medina, Islam's holiest sites, many Muslims were upset at the permanent military presence. The continued presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia after the war was one of the stated motivations behind the 11 September terrorist attacks,[153] the Khobar Towers bombing, and the date chosen for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings (7 August), which was eight years to the day that U.S. troops were sent to Saudi Arabia.[154] Osama bin Laden interpreted the Islamic prophet Muhammad as banning the "permanent presence of infidels in Arabia".[155] In 1996, bin Laden issued a fatwa, calling for U.S. troops to leave Saudi Arabia. In a December 1999 interview with Rahimullah Yusufzai, bin Laden said he felt that Americans were "too near to Mecca" and considered this a provocation to the entire Islamic world.[156]

Sanctions

Main articles: United Nations Security Council Resolution 661 and Iraq sanctions

On 6 August 1990, after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 661 which imposed economic sanctions on Iraq, providing for a full trade embargo, excluding medical supplies, food and other items of humanitarian necessity, these to be determined by the Council's sanctions committee. From 1991 until 2003, the effects of government policy and sanctions regime led to hyperinflation, widespread poverty and malnutrition.

During the late 1990s, the U.N. considered relaxing the sanctions imposed because of the hardships suffered by ordinary Iraqis. Studies dispute the number of people who died in south and central Iraq during the years of the sanctions.[157][158][159]

Draining of the Qurna Marshes

Main article: Draining of the Qurna Marshes

The draining of the Qurna Marshes was an irrigation project in Iraq during and immediately after the war, to drain a large area of marshes in the Tigris–Euphrates river system. Formerly covering an area of around 3,000 square kilometers, the large complex of wetlands were almost completely emptied of water, and the local Shi'ite population relocated, following the war and 1991 uprisings. By 2000, United Nations Environment Programme estimated that 90% of the marshlands had disappeared, causing desertification of over 7,500 square miles (19,000 km2).

Many international organizations such as the U.N. Human Rights Commission, the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, the Wetlands International, and Middle East Watch have described the project as a political attempt to force the Marsh Arabs out of the area through water diversion tactics.[160]

Oil spill

Main article: Gulf War oil spill

On 23 January, Iraq dumped 400 million US gallons (1,500,000 m3) of crude oil into the Persian Gulf [162], causing the largest offshore oil spill in history at that time.[161] It was reported as a deliberate natural resources attack to keep U.S. Marines from coming ashore (Missouri and Wisconsin had shelled Failaka Island during the war to reinforce the idea that there would be an amphibious assault attempt).[163] About 30–40% of this came from allied raids on Iraqi coastal targets.[164]

Kuwaiti oil fires

Main article: Kuwaiti oil fires

The Kuwaiti oil fires were caused by the Iraqi military setting fire to 700 oil wells as part of a scorched earth policy while retreating from Kuwait in 1991 after conquering the country but being driven out by Coalition forces. The fires started in January and February 1991 and the last one was extinguished by November 1991.[165]

The resulting fires burned out of control because of the dangers of sending in firefighting crews. Land mines had been placed in areas around the oil wells, and a military cleaning of the areas was necessary before the fires could be put out. Somewhere around 6 million barrels (950,000 m3) of oil were lost each day. Eventually, privately contracted crews extinguished the fires, at a total cost of US$1.5 billion to Kuwait.[166] By that time, however, the fires had burned for approximately ten months, causing widespread pollution.

The cost of the war to the United States was calculated by the U.S. Congress to be $61.1 billion.[167] About $52 billion of that amount was paid by other countries: $36 billion by Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and other Arab states of the Persian Gulf; $16 billion by Germany and Japan (which sent no combat forces due to their constitutions). About 25% of Saudi Arabia's contribution was paid in the form of in-kind services to the troops, such as food and transportation.[167] U.S. troops represented about 74% of the combined force, and the global cost was therefore higher.

Effect on developing countries

Apart from the impact on the Gulf states themselves, the resulting economic disruptions after the crisis affected many states. The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) undertook a study in 1991 to assess the effects on developing states and the international community's response. A briefing paper finalized on the day that the conflict ended draws on their findings which had two main conclusions: Many developing states were severely affected and while there has been a considerable response to the crisis, the distribution of assistance was highly selective.[168]

The ODI factored in elements of "cost" which included oil imports, remittance flows, re-settlement costs, loss of export earnings and tourism. For Egypt, the cost totaled $1 billion, 3% of GDP. Yemen had a cost of $830 million, 10% of GDP, while it cost Jordan $1.8 billion, 32% of GDP.

International response to the crisis on developing states came with the channeling of aid through The Gulf Crisis Financial Co-ordination Group. They were 24 states, comprising most of the OECD countries plus some Gulf states: Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait. The members of this group agreed to disperse $14 billion in development assistance.

The World Bank responded by speeding up the disbursement of existing project and adjustment loans. The International Monetary Fund adopted two lending facilities – the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) and the Compensatory & Contingency Financing Facility (CCFF). The European Community offered $2 billion in assistance.[168]

Media coverage

The war was heavily televised. For the first time, people all over the world were able to watch live pictures of missiles hitting their targets and fighters departing from aircraft carriers. Allied forces were keen to demonstrate their weapons' accuracy.

In the United States, the "big three" network anchors led the war's network news coverage: ABC's Peter Jennings, CBS's Dan Rather, and NBC's Tom Brokaw were anchoring their evening newscasts when air strikes began on 16 January 1991. ABC News correspondent Gary Shepard, reporting live from Baghdad, told Jennings of the city's quietness. But, moments later, Shepard was back on the air as flashes of light were seen on the horizon and tracer fire was heard on the ground.

On CBS, viewers were watching a report from correspondent Allen Pizzey, who was also reporting from Baghdad, when the war began. Rather, after the report was finished, announced that there were unconfirmed reports of flashes in Baghdad and heavy air traffic at bases in Saudi Arabia. On the "NBC Nightly News", correspondent Mike Boettcher reported unusual air activity in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Moments later, Brokaw announced to his viewers that the air attack had begun.

Still, it was CNN whose coverage gained the most popularity and indeed its wartime coverage is often cited as one of the landmark events in the network's development. CNN correspondents John Holliman and Peter Arnett and CNN anchor Bernard Shaw relayed audio reports from Baghdad's Al-Rashid Hotel as the air strikes began. The network had previously convinced the Iraqi government to allow installation of a permanent audio circuit in their makeshift bureau. When the telephones of all of the other Western TV correspondents went dead during the bombing, CNN was the only service able to provide live reporting. After the initial bombing, Arnett remained behind and was, for a time, the only American TV correspondent reporting from Iraq.

In the United Kingdom, the BBC devoted the FM portion of its national speech radio station BBC Radio 4 to an eighteen-hour rolling news format creating Radio 4 News FM. The station was short lived, ending shortly after President Bush declared the ceasefire and Kuwait's liberation. However, it paved the way for the later introduction of Radio Five Live.

Two BBC journalists, John Simpson and Bob Simpson (no relation), defied their editors and remained in Baghdad to report on the war's progress. They were responsible for a report which included an "infamous cruise missile that travelled down a street and turned left at a traffic light."[169]

Newspapers all over the world also covered the war and Time magazine published a special issue dated 28 January 1991, the headline "WAR IN THE GULF" emblazoned on the cover over a picture of Baghdad taken as the war began.

U.S. policy regarding media freedom was much more restrictive than in the Vietnam War. The policy had been spelled out in a Pentagon document entitled Annex Foxtrot. Most of the press information came from briefings organized by the military. Only selected journalists were allowed to visit the front lines or conduct interviews with soldiers. Those visits were always conducted in the presence of officers, and were subject to both prior approval by the military and censorship afterward. This was ostensibly to protect sensitive information from being revealed to Iraq. This policy was heavily influenced by the military's experience with the Vietnam War, in which public opposition within the U.S. grew throughout the war's course. It wasn't only the limitation of information in the Middle East; media were also restricting what was shown about the war with more graphic depictions like Ken Jarecke's image of a burnt Iraqi soldier being pulled from the American AP wire whereas in Europe it was given extensive coverage.[170][171][172]

At the same time, the war's coverage was new in its instantaneousness. About halfway through the war, Iraq's government decided to allow live satellite transmissions from the country by Western news organizations, and U.S. journalists returned en masse to Baghdad. NBC's Tom Aspell, ABC's Bill Blakemore, and CBS News' Betsy Aaronfiled filed reports, subject to acknowledged Iraqi censorship. Throughout the war, footage of incoming missiles was broadcast almost immediately.

A British crew from CBS News (David Green and Andy Thompson), equipped with satellite transmission equipment traveled with the front line forces and, having transmitted live TV pictures of the fighting en route, arrived the day before the forces in Kuwait City, broadcasting live television from the city and covering the entrance of the Arab forces the next day.

Alternative media outlets provided views in opposition to the war. Deep Dish Television compiled segments from independent producers in the U.S. and abroad, and produced a ten-hour series that was distributed internationally, called The Gulf Crisis TV Project. The series' first program War, Oil and Power was compiled and released in 1990, before the war broke out. News World Order was the title of another program in the series; it focused on the media's complicity in promoting the war, as well as Americans' reactions to the media coverage. In San Francisco, as a local example, Paper Tiger Television West produced a weekly cable television show with highlights of mass demonstrations, artists' actions, lectures, and protests against mainstream media coverage at newspaper offices and television stations. Local media outlets in cities across the country screened similar oppositional media.

The organization Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) critically analyzed media coverage during the war in various articles and books, such as the 1991 Gulf War Coverage: The Worst Censorship was at Home.[173]

Technology

Precision-guided munitions, such as the U.S. Air Force's AGM-130 guided missile, were heralded as key in allowing military strikes to be made with a minimum of civilian casualties compared to previous wars, although they weren't used as often as more traditional, less accurate bombs. Specific buildings in downtown Baghdad could be bombed while journalists in their hotels watched cruise missiles fly by.

Precision-guided munitions amounted to approximately 7.4% of all bombs dropped by the Coalition. Other bombs included cluster bombs, which disperse numerous submunitions,[174] and daisy cutters, 15,000-pound bombs which can disintegrate everything within hundreds of yards.

Global Positioning System units were important in enabling Coalition units to easily navigate across the desert. Since military GPS receivers were not avai.

Share this page