L.A. sheriff: Pay for preschool, not prisons

USINFO | 2013-09-30 14:01

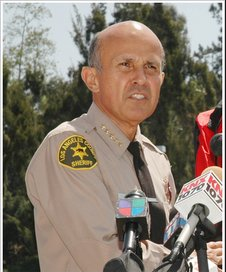

The man who runs the nation’s largest jail system came to Washington on Monday to promote what he considers a potent tool in crime-fighting: universal pre-school.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Leroy Baca is heading a lobbying effort by more than 1,000 police chiefs, sheriffs and prosecutors to convince Congress to enact the Obama administration’s plan to expand preschool to every 4-year-old in the country.

“Either you have to pay now (for preschool), or you’re going to have to pay a guy like me later,” Baca said. He oversees a jail system with 19,000 inmates.

About 60 percent of those behind bars in Los Angeles are high school dropouts, said Baca, adding that many struggled in school because they did not have the benefit of preschool during their earliest years.

“When children go to preschool, they get to kindergarten with social confidence,” said Baca, 71, who worked as a part-time teacher in middle and high school and adult education classes for 30 years, in addition to his criminal justice career.

“They’re more sensitive about others,” Baca said. “You don’t steal from people as easily (if you attend preschool), you’re not as destructive, you acquire the skills to be socially engaged at an early age.”

Advances in neuroscience over the past decade suggest that the window between birth and age 5 is a critical period of rapid learning and brain development.

“I would rather invest in children than in jails,” said Baca, who is heading a new group known as Fight Crime: Invest in Kids. The Los Angeles County jail spends about $35,000 a year to house and feed each inmate, he said.

President Obama has made a sweeping expansion of preschool education a priority for his second term. He wants to see universal preschool for 4-year-olds, saying that quality early childhood education pays huge dividends by boosting graduation rates, reducing teen pregnancy and bringing down violent crime. Early education for low-income children is estimated to generate $4 to $11 in benefits for every dollar spent on the program, according to a 2011 cost-benefit analysis funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Obama wants to raise $75 billion over the next decade for the plan by doubling the federal tax on cigarettes from $1.01 to $1.95 per pack. They money would allow all low-income and some moderate-income 4-year-olds to attend preschool.

The plan would expand such preschool services to 1.1 million additional 4-year-olds, according to the Education Department.

That idea has been attacked by tobacco companies and is anathema to many anti-tax Republicans.

The administration has said the plan will be a partnership with the states. In the first two years, the federal government would pay 91 percent of the costs, with participating states paying 9 percent. The ratio would gradually shift until the states are paying 75 percent and the federal government 25 percent by the 10th year.

In addition to preschool, Obama is seeking $15 billion for education programs for babies and toddlers.

Four Democratic senators — Patty Murray (Washington), Tom Harkin (Iowa), Bob Casey (Pennsylvania) and Mazie Hirono (Hawaii) — are working on legislation that would incorporate Obama’s preschool plan.

Nearly half of all 4-year-olds and about 20 percent of 3-year-olds were enrolled in state-funded or federally funded preschool programs in 2011, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University. Those state-funded programs cost taxpayers about $5.5 billion, an average of about $5,000 per child.

The 2008 recession slowed or halted growth of programs, but in recent months, lawmakers in several states have been talking about how to expand access to preschool. In 2013, 24 states either debated expanding or expanded state-funded preschool programs, according to Fight Crime: Invest in Kids. More than half of those states have Republican governors, the group said.

Still, 10 states do not fund preschool of any kind. Several, including Indiana, do not compel children to attend kindergarten, so some children first enroll in school in first grade at ages 6 or 7.

Baca helped create a program that allows inmates to receive an education while behind bars.

Five of those inmates have asked a judge to extend their sentence so they can finish their studies and receive a high school diploma, Baca said.

Of the inmates who spent their time in jail learning, 19 percent ended up returning to jail, or half the recidivism rate of the general jail population, he said.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Leroy Baca is heading a lobbying effort by more than 1,000 police chiefs, sheriffs and prosecutors to convince Congress to enact the Obama administration’s plan to expand preschool to every 4-year-old in the country.

“Either you have to pay now (for preschool), or you’re going to have to pay a guy like me later,” Baca said. He oversees a jail system with 19,000 inmates.

About 60 percent of those behind bars in Los Angeles are high school dropouts, said Baca, adding that many struggled in school because they did not have the benefit of preschool during their earliest years.

“When children go to preschool, they get to kindergarten with social confidence,” said Baca, 71, who worked as a part-time teacher in middle and high school and adult education classes for 30 years, in addition to his criminal justice career.

“They’re more sensitive about others,” Baca said. “You don’t steal from people as easily (if you attend preschool), you’re not as destructive, you acquire the skills to be socially engaged at an early age.”

Advances in neuroscience over the past decade suggest that the window between birth and age 5 is a critical period of rapid learning and brain development.

“I would rather invest in children than in jails,” said Baca, who is heading a new group known as Fight Crime: Invest in Kids. The Los Angeles County jail spends about $35,000 a year to house and feed each inmate, he said.

President Obama has made a sweeping expansion of preschool education a priority for his second term. He wants to see universal preschool for 4-year-olds, saying that quality early childhood education pays huge dividends by boosting graduation rates, reducing teen pregnancy and bringing down violent crime. Early education for low-income children is estimated to generate $4 to $11 in benefits for every dollar spent on the program, according to a 2011 cost-benefit analysis funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Obama wants to raise $75 billion over the next decade for the plan by doubling the federal tax on cigarettes from $1.01 to $1.95 per pack. They money would allow all low-income and some moderate-income 4-year-olds to attend preschool.

The plan would expand such preschool services to 1.1 million additional 4-year-olds, according to the Education Department.

That idea has been attacked by tobacco companies and is anathema to many anti-tax Republicans.

The administration has said the plan will be a partnership with the states. In the first two years, the federal government would pay 91 percent of the costs, with participating states paying 9 percent. The ratio would gradually shift until the states are paying 75 percent and the federal government 25 percent by the 10th year.

In addition to preschool, Obama is seeking $15 billion for education programs for babies and toddlers.

Four Democratic senators — Patty Murray (Washington), Tom Harkin (Iowa), Bob Casey (Pennsylvania) and Mazie Hirono (Hawaii) — are working on legislation that would incorporate Obama’s preschool plan.

Nearly half of all 4-year-olds and about 20 percent of 3-year-olds were enrolled in state-funded or federally funded preschool programs in 2011, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University. Those state-funded programs cost taxpayers about $5.5 billion, an average of about $5,000 per child.

The 2008 recession slowed or halted growth of programs, but in recent months, lawmakers in several states have been talking about how to expand access to preschool. In 2013, 24 states either debated expanding or expanded state-funded preschool programs, according to Fight Crime: Invest in Kids. More than half of those states have Republican governors, the group said.

Still, 10 states do not fund preschool of any kind. Several, including Indiana, do not compel children to attend kindergarten, so some children first enroll in school in first grade at ages 6 or 7.

Baca helped create a program that allows inmates to receive an education while behind bars.

Five of those inmates have asked a judge to extend their sentence so they can finish their studies and receive a high school diploma, Baca said.

Of the inmates who spent their time in jail learning, 19 percent ended up returning to jail, or half the recidivism rate of the general jail population, he said.

Share this page