You’re on White House Candid Camera

USINFO | 2013-09-30 11:20

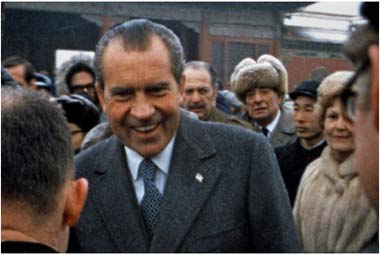

These days, Dwight Chapin shoots movies on his iPad. But in the Richard M. Nixon White House, he and his colleagues John Ehrlichman and H. R. Haldeman were Super 8-wielding auteurs, capturing intimate moments that eluded the press corps: Tricia Nixon before her wedding; the president in Beijing enjoying a ballet about a workers’ insurrection; Pope Paul VI shot sideways (because Haldeman had smuggled his camera into the Vatican).

The images, surreptitious and otherwise, are included in “Our Nixon,” the impressionistic documentary directed by Penny Lane that has its premiere Thursday on CNN. The film makes use of hundreds of reels of home movies shot by Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Mr. Chapin, some of which had been confiscated by the F.B.I. during the Watergate investigation. The footage remained largely unseen for 40 years.

“They weren’t being hidden,” Ms. Lane said. “They were being ignored.”

A Kickstarter campaign by Ms. Lane and her co-producer, Brian Frye, helped pay for transfers of the material, the rights to which were in the public domain, from the National Archive. They spent two years making their film, which was originally intended to be about the personalities revealed, rather than hard-core Nixon history.

“We didn’t even want to mention Watergate,” Ms. Lane, 35, said with a laugh, over breakfast in Manhattan. “There are so many great books, and so much research. What we were interested in were the human casualties, the people who got caught up in it, and who went down.”

At the heart of the documentary are nearly 4,000 hours of audio from the infamous Oval Office taping system, 500 reels of Super 8 confiscated by the F.B.I. from Ehrlichman’s desk after his resignation in 1973, and original footage donated by Haldeman’s family to the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in 2012. It provides a unique look at a doomed presidency that can still start arguments.

“We know that people come into the film with a lot of baggage,” Ms. Lane said. “There are people who say, ‘I can’t hear John Ehrlichman’s voice without my stomach hurting.’ And there’s the Nixon loyalist side, which has its own very strong feelings about, say, Dan Rather, or Daniel Ellsberg.”

The loyalist side includes Mr. Chapin, the former deputy assistant to the president and the lone surviving member of the White House movie crew. (Haldeman died in 1993, Ehrlichman in 1999.) All three served prison time for Watergate-related crimes. Among the aspects of the documentary Mr. Chapin takes exception to is the juxtaposition of Nixon’s famous “Silent Majority” speech of Nov. 3, 1969, and a telephone conversation with Haldeman that seems to address the same speech.

That telephone call never existed, Mr. Chapin said from Yorba Linda, Calif. (home of the Nixon Library) because the Nixon taping system had not yet been installed.

“That conversation,” he said, “was about a speech much later in the administration. Penny didn’t have anything, so she lifted that discussion from later in the administration and brought it into the Nov. 3 speech. That is obviously creative license, but if you’re representing your film as documentary, it becomes a piece of propaganda.

“I don’t mean to be a fly in the ointment,” Mr. Chapin added. “But when you’re watching it with a group of people, the audience laughs, and they’re laughing at President Nixon based on something that’s not a factual representation.”

Ms. Lane, who has been making short documentaries since 2004 (“Nixon” is her feature-length debut), conceded that she exercised artistic license in the film and happily cataloged instances where the movie did not proceed chronologically, or where material was edited for clarity.

“All of which I told Dwight,” she said. “But I think that to him, any creative license, including the kind of summaries and simplifications that are just necessary to filmmaking, is a problem.”

Mr. Frye, who teaches about intellectual property and art at the University of Kentucky College of Law, said that the other material in the film — like newscasts and interviews. — are there to provide a context that the home movies lacked.

“We tried very hard to be very rigorous in avoiding anything that would cause people to believe something factually inaccurate,” he said. “But when you make a movie, you make aesthetic choices, especially working with archive material. There was a lot of massaging to make some sense out of what we had.”

Amy Entelis, senior vice president for development for CNN Worldwide, said “Our Nixon” was an obvious choice for the fledgling CNN Films. (Cinedigm will release the film theatrically Aug. 30.) “So much material was original, and the story is told in an unconventional way.” she said.

Further programming can be spun off a film like this, she added. Whether Mr. Chapin will be part of it is a question. Two years ago, he was asked by Ms. Lane to cooperate with her film, and he said no.

“The first I knew it was completed was when I was having breakfast with Carl Bernstein,” he said of the former Washington Post reporter who broke the Watergate story with Bob Woodward. (Mr. Chapin, apparently, doesn’t hold grudges.) “We ran into each other in the Hamptons, and he asked if I’d seen it, and I said no. Penny sent a link.”

Based on watching it four times, “I think the characterization of President Nixon is very stereotyped,” he said. “She viewed and projected exactly what people are sick of seeing. It does not zero in on the incredible six decades of political life he had and his contribution to the country.”

Ms. Lane wouldn’t necessary disagree, not about the president. “I think that Nixon’s presidency is slowly emerging out of the shadow of Watergate,” she said. Her own interest, however, is what the White House films say about the three men behind the cameras.

“They looked so excited,” she said. “It seemed so obvious that they thought they were doing something great. It was so sad. They’re all going to prison. And they don’t know that.”

Share this page