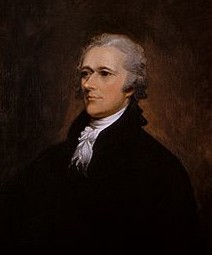

Alexander Hamilton

wikipedia.org | 2013-01-07 15:11

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757[1] – July 12, 1804) was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America's first constitutional lawyers and the first United States Secretary of the Treasury.

As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton was the primary author of the economic policies of the George Washington administration, especially the funding of the state debts by the Federal government, the establishment of a national bank, a system of tariffs, and friendly trade relations with Britain. He became the leader of the Federalist Party, created largely in support of his views, and was opposed by the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Hamilton served in the American Revolutionary War. At the start of the war, he organized an artillery company and was chosen as its captain. He later became the senior aide-de-camp and confidant to General George Washington, the American commander-in-chief. He served again under Washington in the army raised to defeat the Whiskey Rebellion, a tax revolt of western farmers in 1794. In 1798, Hamilton called for mobilization against France after the XYZ Affair and secured an appointment as commander of a new army, which he trained for a war. However, the Quasi-War, although hard-fought at sea, was never officially declared. In the end, President John Adams found a diplomatic solution that avoided war.

Born out of wedlock and raised in the West Indies, Hamilton was effectively orphaned at about the age of 11. Recognized for his abilities and talent, he was sponsored by people from his community to go to the North American mainland for his education. He attended King's College (now Columbia University), in New York City. After the American Revolutionary War, Hamilton was elected to the Continental Congress from New York. He resigned to practice law and founded the Bank of New York.

Hamilton was among those dissatisfied with the Articles of Confederation—the first attempt at a national governing document—because it lacked an executive, courts, and taxing powers. He led the Annapolis Convention, which successfully influenced Congress to issue a call for the Philadelphia Convention in order to create a new constitution. He was an active participant at Philadelphia and helped achieve ratification by writing 51 of the 85 installments of the Federalist Papers, which supported the new constitution and to this day is the single most important source for Constitutional interpretation. In the new government under President George Washington, Hamilton was appointed the Secretary of the Treasury. An admirer of British political systems, Hamilton was a nationalist who emphasized strong central government and successfully argued that the implied powers of the Constitution could be used to fund the national debt, assume state debts, and create the government-owned Bank of the United States. These programs were funded primarily by a tariff on imports and later also by a highly controversial excise tax on whiskey.

Embarrassed when a extra-marital affair from his past became public, Hamilton resigned from office in 1795 and returned to the practice of law in New York. He kept his hand in politics and was a powerful influence on the cabinet of President Adams (1797–1801). Hamilton's opposition to Adams' re-election helped cause his defeat in the 1800 election. When in the same contest Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied for the presidency in the electoral college, Hamilton helped defeat Burr, whom he found unprincipled, and elect Jefferson despite philosophical differences. After failing to support Adams, the Federalist candidate, Hamilton lost some national prominence within the party. Vice President Burr later ran for governor in New York State, but Hamilton's influence in his home state was strong enough to prevent a Burr victory. Taking offense at some of Hamilton's comments, Burr challenged him to a duel and mortally wounded Hamilton, who died within days.

Childhood in the Caribbean

Alexander Hamilton was born in Charlestown, the capital of the island of Nevis, in the Leeward Islands; Nevis was then one of the British West Indies. Hamilton was born out of wedlock to Rachel Faucette Buck, a married woman of partial French Huguenot descent, and James A. Hamilton, the fourth son of the Scottish laird Alexander Hamilton of Grange, Ayrshire.

The birthplace and early childhood home of Alexander Hamilton, in Nevis, West Indies

His mother moved with the infant Hamilton to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands, then ruled by Denmark. It is not certain whether the year of Hamilton's birth was 1757 or 1755; most historical evidence after Hamilton's arrival in North America supports the idea that he was born in 1757, and many historians had accepted this birth date. Hamilton's early life in the Caribbean was recorded in documents first published in Danish in 1930; this evidence has caused historians since then to opt for a birth year of 1755.

Hamilton listed his birth year as 1757 when he first arrived in the Thirteen Colonies. He celebrated his birthday on January 11. In later life, he tended to give his age only in round figures. Probate papers from St. Croix in 1768, after the death of Hamilton's mother, list him as then 13 years old,a date that would support a birth year of 1755. Historians have explained the different birth years by the following: If 1755 is correct, Hamilton may have been trying to appear younger than his college classmates or perhaps wished to avoid standing out as older; on the other hand, if 1757 is correct, the probate document indicating a birth year of 1755 may have been in error, or Hamilton may have been attempting to pass as 13, in order to be more employable after his mother's death.

Hamilton in his youth

Hamilton's mother had been married previously to Johann Michael Lavien of St. Croix, a much older merchant planter, who is described in some accounts as Danish-Jewish. To escape this unhappy marriage, Rachel left her husband and first son, traveling to St. Kitts in 1750, where she met James Hamilton. Hamilton and Rachel moved together to Rachel's birthplace, Nevis, where she had inherited property from her father. Their two sons were James, Jr., and Alexander. Because Alexander Hamilton's parents were not legally married, the Church of England denied him membership and education in the church school. Hamilton received "individual tutoring" and classes in a private school led by a Jewish headmistress. Hamilton supplemented his education with a family library of thirty-four books, including Greek and Roman classics.

Hamilton's father James abandoned Rachel and their two sons, allegedly to "spar[e] a charge of bigamy . . . after finding out that her first husband intend[ed] to divorce her under Danish law on grounds of adultery and desertion." Rachel supported her family in St. Croix by keeping a small store in Christiansted. She contracted a severe fever and died on February 19, 1768, 1:02 am, leaving Hamilton effectively orphaned. This may have had severe emotional consequences for him, even by the standards of an eighteenth-century childhood. In probate court, Rachel's "first husband seized her estate" and obtained the few valuables Rachel had owned, including some household silver. Many items were auctioned off, but a friend purchased the family books and returned them to the young Hamilton.

Hamilton became a clerk at a local import-export firm, Beekman and Cruger, which traded with New England; he was left in charge of the firm for five months in 1771, while the owner was at sea. He and his older brother James were adopted briefly by a cousin, Peter Lytton, but when Lytton committed suicide, the brothers were separated. James apprenticed with a local carpenter, while Alexander was adopted by a Nevis merchant, Thomas Stevens. According to the writer Ron Chernow, some evidence suggests that Stevens may have been Alexander Hamilton's biological father: his son, Edward Stevens, became a close friend of Hamilton. The two boys were described as looking much alike, were both fluent in French, and shared similar interests.

Hamilton continued clerking, but he remained an avid reader, later developed an interest in writing, and began to desire a life outside the small island where he lived. He wrote an essay published in the Royal Danish-American Gazette, a detailed account of a hurricane that had devastated Christiansted on August 30, 1772. The essay impressed community leaders, who collected a fund to send the young Hamilton to the North American colonies for his education.

Education

Statue of Hamilton outside Hamilton Hall overlooking Hamilton Lawn at his alma mater, Columbia University in New York City

In the autumn of 1772, Hamilton arrived by way of Boston, Massachusetts, at Elizabethtown Academy, a grammar school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. In 1773 he studied with Francis Barber at Elizabethtown in preparation for college work. He came under the influence of William Livingston, a leading intellectual and revolutionary, with whom he lived for a time at his Liberty Hall.

Hamilton applied to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), asking to be allowed to study at a quicker pace and complete his studies in a shorter time.[20] The college's Board of Trustees refused his request. Hamilton made a similar request to King's College in New York City (now Columbia University), was accepted, and entered the college in late 1773 or early 1774.

Hamilton Lawn separates Hamilton Hall and John Jay Hall at Columbia University

When the Church of England clergyman Samuel Seabury published a series of pamphlets promoting the Loyalist cause the following year, Hamilton responded with his first political writings, "A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress" and "The Farmer Refuted". He published two additional pieces attacking the Quebec Act as well as fourteen anonymous installments of "The Monitor" for Holt's New York Journal. Although Hamilton was a supporter of the Revolutionary cause at this prewar stage, he did not approve of mob reprisals against Loyalists. On May 10, 1775, Hamilton saved his college president Myles Cooper, a Loyalist, from an angry mob by speaking to the crowd long enough for Cooper to escape.

During the Revolutionary War

Alexander Hamilton in the Uniform of the New York Artillery by Alonzo Chappel (1828–1887)

Early military career

In 1775, after the first engagement of American troops with the British in Boston, Hamilton joined a New York volunteer militia company called the Hearts of Oak, which included other King's College students. He drilled with the company, before classes, in the graveyard of nearby St. Paul's Chapel. Hamilton studied military history and tactics on his own and achieved the rank of lieutenant. Under fire from HMS Asia, he led a successful raid for British cannon in the Battery, the capture of which resulted in the Hearts of Oak becoming an artillery company thereafter.

Through his connections with influential New York patriots such as Alexander McDougall and John Jay, he raised the New York Provincial Company of Artillery of sixty men in 1776, and was elected captain. It took part in the campaign of 1776 around New York City, particularly at the Battle of White Plains; at the Battle of Trenton, it was stationed at the high point of town, the meeting of the present Warren and Broad Streets, to keep the Hessians pinned in the Trenton Barracks.

Through his connections with influential New York patriots such as Alexander McDougall and John Jay, he raised the New York Provincial Company of Artillery of sixty men in 1776, and was elected captain. It took part in the campaign of 1776 around New York City, particularly at the Battle of White Plains; at the Battle of Trenton, it was stationed at the high point of town, the meeting of the present Warren and Broad Streets, to keep the Hessians pinned in the Trenton Barracks.

Washington's staff

Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, 1787

Hamilton was invited to become an aide to Nathanael Greene and to Henry Knox; however, he declined these invitations, believing his best chance for improving his station in life was glory on the battlefield. Hamilton eventually received an invitation he felt he could not refuse: to serve as Washington's aide, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.[26] Hamilton served for four years as Washington's chief of staff. He handled letters to Congress, state governors, and the most powerful generals in the Continental Army; he drafted many of Washington's orders and letters at the latter's direction; he eventually issued orders from Washington over Hamilton's own signature. Hamilton was involved in a wide variety of high-level duties, including intelligence, diplomacy, and negotiation with senior army officers as Washington's emissary. The important duties with which he was entrusted attest to Washington's deep confidence in his abilities and character, then and afterward. At the points in their relationship when there was little personal attachment, there was still always a reciprocal confidence and respect.

During the war, Hamilton became close friends with several fellow officers. His letters to the Marquis de Lafayette and to John Laurens, employing the sentimental literary conventions of the late eighteenth century and alluding to Greek history and mythology, have been read by Jonathan Katz as revealing a homosocial or perhaps homosexual relationship, but few historians agree.

Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown by John Trumbull, oil on canvas, 1820

Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler on December 14, 1780. She was the daughter of Philip Schuyler, a general and wealthy landowner from one of the most prominent families in the state of New York. The marriage took place at Schuyler Mansion in Albany, New York.

Hamilton was also close to Eliza's older sister, Angelica, who eloped with John Barker Church, an Englishman who made a fortune in the American colonies during the Revolution. She returned with Church to London after the war, where she later become a joint friend of Maria Cosway and Thomas Jefferson.

While on Washington's staff, Hamilton long sought command and a return to active combat. As the war drew nearer to a close, he knew that opportunities for military glory were fading. In February 1781, Hamilton was mildly reprimanded by Washington, and used this as an excuse to resign his staff position. He asked Washington and others for a field command. This continued until early July 1781, when Hamilton submitted a letter to Washington with his commission enclosed, "thus tacitly threatening to resign if he didn't get his desired command."

On July 31, 1781, Washington relented and assigned Hamilton as commander of a New York light infantry battalion. In the planning for the assault on Yorktown, Hamilton was given command of three battalions, which were to fight in conjunction with French troops in taking Redoubts No. 9 and No. 10 of the British fortifications at Yorktown. Hamilton and his battalions fought bravely and took Redoubt No. 10 with bayonets in a nighttime action, as planned. The French also fought bravely, took heavy casualties, and successfully took Redoubt #9. This action forced the British surrender of an entire army at Yorktown, effectively ending major British military operations in North America.

Hamilton enters Congress

After the Battle of Yorktown, Hamilton resigned his commission. He was elected in July 1782 to the Congress of the Confederation as a New York representative for the term beginning in November 1782. Hamilton supported congressmen such as Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris, his assistant Gouverneur Morris (no relation), along with James Wilson and James Madison, to provide the Congress with the independent source of revenue it lacked under the Articles of Confederation.

While on Washington's staff, Hamilton had become frustrated with the decentralized nature of the wartime Continental Congress, particularly its dependence upon the states for financial support. Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress had no power to collect taxes or to demand money from the states. This lack of a stable source of funding had made it difficult for the Continental Army both to obtain its necessary provisions and to pay its soldiers. During the war, and for some time after, Congress obtained what funds it could from subsidies from the King of France, from aid requested from the several states (which were often unable or unwilling to contribute), and from European loans.

An amendment to the Articles had been proposed by Thomas Burke, in February 1781, to give Congress the power to collect a 5% impost, or duty on all imports, but this required ratification by all states; securing its passage as law proved impossible after it was rejected by Rhode Island in November 1782. Madison joined Hamilton in persuading Congress to send a delegation to persuade Rhode Island to change its mind. Their report recommending the delegation argued the federal government needed not just some level of financial autonomy, but also the ability to make laws that superseded those of the individual states. Hamilton transmitted a letter arguing that Congress already had the power to tax, since it had the power to fix the sums due from the several states; but Virginia's rescission of its own ratification ended the Rhode Island negotiations.

Congress and the Army

While Hamilton was in Congress, discontented soldiers began to pose a danger to the young United States. Most of the army was then posted at Newburgh, New York. Those in the army were paying for much of their own supplies, and they had not been paid in eight months. Furthermore, the Continental officers had been promised, in May 1778, after Valley Forge, a pension of half their pay when they were discharged.It was at this time that a group of officers organized under the leadership of General Henry Knox sent a delegation to lobby Congress, led by Capt. Alexander MacDougall (see above). The officers had three demands: the Army's pay, their own pensions, and commutation of those pensions into a lump-sum payment.

Several Congressmen, including Hamilton and the Morrises, attempted to use this Newburgh Conspiracy as leverage to secure independent support from the states and in Congress for funding of the confederal government. They encouraged MacDougall to continue his aggressive approach, threatening unknown consequences if their demands were not met, and defeated proposals that would have resolved the crisis without establishing general federal taxation: that the states assume the debt to the army, or that an impost be established dedicated to the sole purpose of paying that debt. Hamilton suggested using the Army's claims to prevail upon the states for the proposed national funding system. The Morrises and Hamilton contacted Knox to suggest he and the officers defy civil authority, at least by not disbanding if the army were not satisfied; Hamilton wrote Washington to suggest that Hamilton covertly "take direction" of the officers' efforts to secure redress, to secure continental funding but keep the army within the limits of moderation. Washington wrote Hamilton back, declining to introduce the army; after the crisis had ended, he warned of the dangers of using the army as leverage to gain support for the national funding plan.

On March 15, Washington defused the Newburgh situation by giving a speech to the officers. Congress ordered the Army officially disbanded in April 1783. In the same month, Congress passed a new measure for a twenty-five-year impost—which Hamilton voted against—that again required the consent of all the states; it also approved a commutation of the officers' pensions to five years of full pay. Rhode Island again opposed these provisions, and Hamilton's robust assertions of national prerogatives in his previous letter were widely held to be excessive.The Continental Congress was never able to secure full ratification for back pay, pensions, or its own independent sources of funding.

In June 1783, a different group of disgruntled soldiers from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, sent Congress a petition demanding their back pay. When they began to march toward Philadelphia, Congress charged Hamilton and two others with intercepting the mob.

Hamilton requested militia from Pennsylvania's Supreme Executive Council, but was turned down. Hamilton instructed Assistant Secretary of War William Jackson to intercept the men. Jackson was unsuccessful. The mob arrived in Philadelphia, and the soldiers proceeded to harangue Congress for their pay. The President of Congress, John Dickinson, feared that the Pennsylvania state militia was unreliable, and refused its help. Hamilton argued that Congress ought to adjourn to Princeton, New Jersey. Congress agreed, and relocated there.

Frustrated with the weakness of the central government, Hamilton while in Princeton drafted a call to revise the Articles of Confederation. This resolution contained many features of the future US Constitution, including a strong federal government with the ability to collect taxes and raise an army. It also included the separation of powers into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches.

Return to New York

Hamilton resigned from Congress, and in July 1783 was admitted to the New York Bar after several months of self-directed education.He practiced law in New York City in partnership with Richard Harison. He specialized in defending Tories and British subjects, as in Rutgers v. Waddington, in which he defeated a claim for damages done to a brewery by the Englishmen who held it during the military occupation of New York. He pleaded for the Mayor's Court to interpret state law consistent with the 1783 Treaty of Paris which had ended the Revolutionary War.

In 1784, he founded the Bank of New York, now the oldest ongoing bank in the United States. Hamilton was one of the men who restored King's College, which had been suspended since 1776 and severely damaged during the War, as Columbia College. Long dissatisfied with the weak Articles of Confederation, he played a major leadership role at the Annapolis Convention in 1786. He drafted its resolution for a constitutional convention, and in doing so brought his longtime desire to have a more powerful, more financially independent federal government one step closer to reality.

Constitution and Federalist Papers

Hamilton shortly after the American Revolution

In 1787, Hamilton served as assemblyman from New York County in the New York State Legislature and was the first delegate chosen to the Constitutional Convention. Even though Hamilton had been a leader in calling for a new Constitutional Convention, his direct influence at the Convention itself was quite limited. Governor George Clinton's faction in the New York legislature had chosen New York's other two delegates, John Lansing and Robert Yates, and both of them opposed Hamilton's goal of a strong national government.

Thus, whenever the other two members of the New York delegation were present, they decided New York's vote; and when they left the convention in protest, Hamilton remained but with no vote, since two representatives were required for any state to cast a vote.

Early in the Convention he made a speech proposing a President-for-Life; it had no effect upon the deliberations of the convention.

He proposed to have an elected President and elected Senators who would serve for life, contingent upon "good behavior" and subject to removal for corruption or abuse; this idea contributed later to the hostile view of Hamilton as a monarchist sympathizer, held by James Madison. During the convention, Hamilton constructed a draft for the Constitution based on the convention debates, but he never presented it. This draft had most of the features of the actual Constitution, including such details as the three-fifths clause. In this draft, the Senate was to be elected in proportion to the population, being two-fifths the size of the House, and the President and Senators were to be elected through complex multistage elections, in which chosen electors would elect smaller bodies of electors; they would hold office for life, but were removable for misconduct. The President would have an absolute veto. The Supreme Court was to have immediate jurisdiction over all law suits involving the United States, and state governors were to be appointed by the federal government.

At the end of the Convention, Hamilton was still not content with the final form of the Constitution, but signed it anyway as a vast improvement over the Articles of Confederation, and urged his fellow delegates to do so also. Since the other two members of the New York delegation, Lansing and Yates, had already withdrawn, Hamilton was the only New York signer to the United States Constitution. He then took a highly active part in the successful campaign for the document's ratification in New York in 1788, which was a crucial step in its national ratification. Hamilton recruited John Jay and James Madison to write a series of essays defending the proposed Constitution, now known as the Federalist Papers, and made the largest contribution to that effort, writing 51 of 85 essays published (Madison wrote 29, Jay only five). Hamilton's essays and arguments were influential in New York state, and elsewhere, during the debates over ratification. The Federalist Papers are more often cited than any other primary source by jurists, lawyers, historians, and political scientists as the major contemporary interpretation of the Constitution.

In 1788, Hamilton served yet another term in what proved to be the last session of the Continental Congress under the Articles of Confederation. When the term of Hamilton's father-in-law Phillip Schuyler was up in 1791, elected in his place was the attorney general of New York, one Aaron Burr. Hamilton blamed Burr for this result, and ill characterizations of Burr appear in his correspondence thereafter. The two men did work together from time to time thereafter on various projects, including Hamilton's army of 1798 and the Manhattan Water Company.

Hamilton, in theFederalist No. 11, 1787, says:

"Let the thirteen States, bound together in a strict and indisoluble Union, concur in erecting one great american system, superior to the control of all trans-Atlantic force or influence and able to dictate the terms of the connection between the old and the new world!"

Share this page