History of Paul Laurence Dunbar High School

USINFO | 2014-01-08 13:49

Dunbar opened in 1918 as the Paul Laurence Dunbar Elementary School, No. 101. It was named in memory of Paul Laurence Dunbar, an African-American poet, who had died ten years earlier. In 1925, a secondary school evolved from the primary grades and was called Dunbar Junior High School, No. 133. Established 1937, by 1940 Dunbar was a full fledged public high school and awarded its first diploma, the second "African American" school in Baltimore to do so.

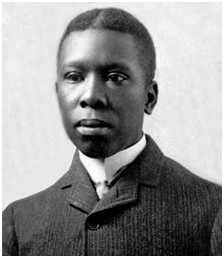

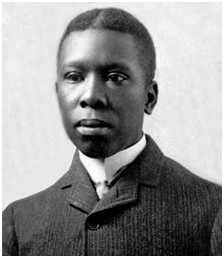

Paul Laurence Dunbar (June 27, 1872 – February 9, 1906) was an African-American poet, novelist, and playwright of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Much of his popular work in his lifetime used a Negro dialect, which helped him become one of the first nationally-accepted African-American writers. Much of his writing, however, does not use dialect; these more traditional poems have become of greater interest to scholars.

Writing career

Dunbar's first professionally published poems were "Our Martyred Soldiers" and "On The River", published in Dayton's The Herald newspaper in 1888. In 1890 Dunbar wrote and edited Dayton's first weekly African-American newspaper, The Tattler, printed by the fledgling company of his high school acquaintances Wilbur and Orville Wright. The paper lasted only 6 weeks.

When his formal schooling ended in 1891, Dunbar took a job as an elevator operator, earning a salary of four dollars a week. The next year, Dunbar asked the Wrights to publish his dialect poems in book form, but the brothers did not have the facility to do so. Dunbar was directed to the United Brethren Publishing House which, in 1893, printed Dunbar's first collection of poetry,Oak and Ivy. Dunbar subsidized the printing of the book himself, though he earned back his investment in two weeks by selling copies personally, often to passengers on his elevator. The larger section of the book, the "Oak" section, consisted of traditional verse whereas the smaller section, the "Ivy", featured light poems written in dialect.

The work attracted the attention of James Whitcomb Riley, the popular "Hoosier Poet". Both Riley and Dunbar wrote poems in both standard English and dialect.

Despite frequently publishing poems and occasionally giving public readings, Dunbar had difficulty financially supporting himself and his mother. Many of his efforts were unpaid and he was a reckless spender, leaving him in debt by the mid-1890s.

On June 27, 1896, the novelist, editor, and critic William Dean Howells published a favorable review of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors. Howells's influence made Dunbar famous and brought national attention to his writing. Though he saw "honest thinking and true feeling" in Dunbar's traditional poems, he particularly praised Dunbar's dialect poems. With his new-found international literary fame, Dunbar collected his first two books into one volume, Lyrics of Lowly Life, which included an introduction by Howells.

Dunbar maintained a lifelong friendship with the Wrights. He was also associated with Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Brand Whitlock (who was described as a close friend). He was honored with a ceremonial sword by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Use of dialect

Much of Dunbar's work was authored in conventional English, while some was rendered in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems. One interviewer reported that Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect", though he is also quoted as saying, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces".

Though he credited William Dean Howells with promoting his early success, Dunbar was dismayed by his demand that he focus on dialect poetry. Angered that editors refused to print his more traditional poems, he accused Howells of "[doing] my irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse." Dunbar, however, was continuing a literary tradition that used Negro dialect; his predecessors included Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, andGeorge Washington Cable.

Two brief examples of Dunbar's work, the first in standard English and the second in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production:

(From "Dreams")

What dreams we have and how they fly

Like rosy clouds across the sky;

Of wealth, of fame, of sure success,

Of love that comes to cheer and bless;

And how they wither, how they fade,

The waning wealth, the jilting jade —

The fame that for a moment gleams,

Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams!

(From "A Warm Day In Winter")

"Sunshine on de medders,

Greenness on de way;

Dat's de blessed reason

I sing all de day."

Look hyeah! What you axing'?

What meks me so merry?

'Spect to see me sighin'

W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary?

Dunbar on 1975 U.S. postage stamp.

Dunbar became the first African-American poet to earn nation-wide distinction and acceptance. The New York Times called him "a true singer of the people — white or black." In his preface to The Book of American Negro Poetry (1931) writer and activist James Weldon Johnson criticized Dunbar's dialect poems for fostering stereotypes of blacks as comical or pathetic and reinforcing the restriction that blacks write only scenes of plantation life.

Writer Maya Angelou called her autobiographical book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) after a line from Dunbar's poem "Sympathy" at the suggestion of jazz musician and activist Abbey Lincoln. Angelou named Dunbar an inspiration for her "writing ambition" and uses his imagery of a caged bird like a chained slave throughout much of her writings.

In 2002, MolefiKete Asante listed Paul Laurence Dunbar on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Dunbar's vaudeville song "Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd" may have influenced the development of "Who dat? Who dat? Who dat say gonna beat dem Saints?", the New Orleans Saints' chant.

Writing career

Dunbar's first professionally published poems were "Our Martyred Soldiers" and "On The River", published in Dayton's The Herald newspaper in 1888. In 1890 Dunbar wrote and edited Dayton's first weekly African-American newspaper, The Tattler, printed by the fledgling company of his high school acquaintances Wilbur and Orville Wright. The paper lasted only 6 weeks.

When his formal schooling ended in 1891, Dunbar took a job as an elevator operator, earning a salary of four dollars a week. The next year, Dunbar asked the Wrights to publish his dialect poems in book form, but the brothers did not have the facility to do so. Dunbar was directed to the United Brethren Publishing House which, in 1893, printed Dunbar's first collection of poetry,Oak and Ivy. Dunbar subsidized the printing of the book himself, though he earned back his investment in two weeks by selling copies personally, often to passengers on his elevator. The larger section of the book, the "Oak" section, consisted of traditional verse whereas the smaller section, the "Ivy", featured light poems written in dialect.

The work attracted the attention of James Whitcomb Riley, the popular "Hoosier Poet". Both Riley and Dunbar wrote poems in both standard English and dialect.

Despite frequently publishing poems and occasionally giving public readings, Dunbar had difficulty financially supporting himself and his mother. Many of his efforts were unpaid and he was a reckless spender, leaving him in debt by the mid-1890s.

On June 27, 1896, the novelist, editor, and critic William Dean Howells published a favorable review of Dunbar's second book, Majors and Minors. Howells's influence made Dunbar famous and brought national attention to his writing. Though he saw "honest thinking and true feeling" in Dunbar's traditional poems, he particularly praised Dunbar's dialect poems. With his new-found international literary fame, Dunbar collected his first two books into one volume, Lyrics of Lowly Life, which included an introduction by Howells.

Dunbar maintained a lifelong friendship with the Wrights. He was also associated with Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Brand Whitlock (who was described as a close friend). He was honored with a ceremonial sword by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Literary style

Dunbar's work is known for its colorful language and a conversational tone, with a brilliant rhetorical structure. These traits were well matched to the tune-writing ability of Carrie Jacobs-Bond (1862–1946), with whom he collaborated.Use of dialect

Much of Dunbar's work was authored in conventional English, while some was rendered in African-American dialect. Dunbar remained always suspicious that there was something demeaning about the marketability of dialect poems. One interviewer reported that Dunbar told him, "I am tired, so tired of dialect", though he is also quoted as saying, "my natural speech is dialect" and "my love is for the Negro pieces".

Though he credited William Dean Howells with promoting his early success, Dunbar was dismayed by his demand that he focus on dialect poetry. Angered that editors refused to print his more traditional poems, he accused Howells of "[doing] my irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse." Dunbar, however, was continuing a literary tradition that used Negro dialect; his predecessors included Mark Twain, Joel Chandler Harris, andGeorge Washington Cable.

Two brief examples of Dunbar's work, the first in standard English and the second in dialect, demonstrate the diversity of the poet's production:

(From "Dreams")

What dreams we have and how they fly

Like rosy clouds across the sky;

Of wealth, of fame, of sure success,

Of love that comes to cheer and bless;

And how they wither, how they fade,

The waning wealth, the jilting jade —

The fame that for a moment gleams,

Then flies forever, — dreams, ah — dreams!

(From "A Warm Day In Winter")

"Sunshine on de medders,

Greenness on de way;

Dat's de blessed reason

I sing all de day."

Look hyeah! What you axing'?

What meks me so merry?

'Spect to see me sighin'

W'en hit's wa'm in Febawary?

Dunbar became the first African-American poet to earn nation-wide distinction and acceptance. The New York Times called him "a true singer of the people — white or black." In his preface to The Book of American Negro Poetry (1931) writer and activist James Weldon Johnson criticized Dunbar's dialect poems for fostering stereotypes of blacks as comical or pathetic and reinforcing the restriction that blacks write only scenes of plantation life.

Writer Maya Angelou called her autobiographical book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) after a line from Dunbar's poem "Sympathy" at the suggestion of jazz musician and activist Abbey Lincoln. Angelou named Dunbar an inspiration for her "writing ambition" and uses his imagery of a caged bird like a chained slave throughout much of her writings.

In 2002, MolefiKete Asante listed Paul Laurence Dunbar on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Dunbar's vaudeville song "Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd" may have influenced the development of "Who dat? Who dat? Who dat say gonna beat dem Saints?", the New Orleans Saints' chant.

Share this page